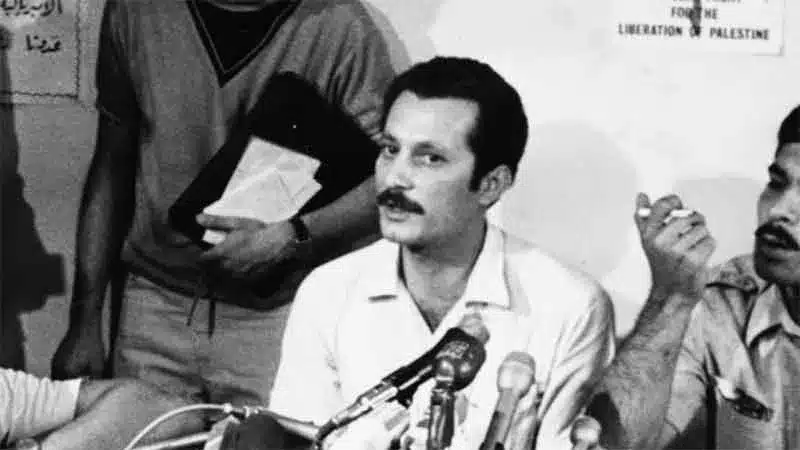

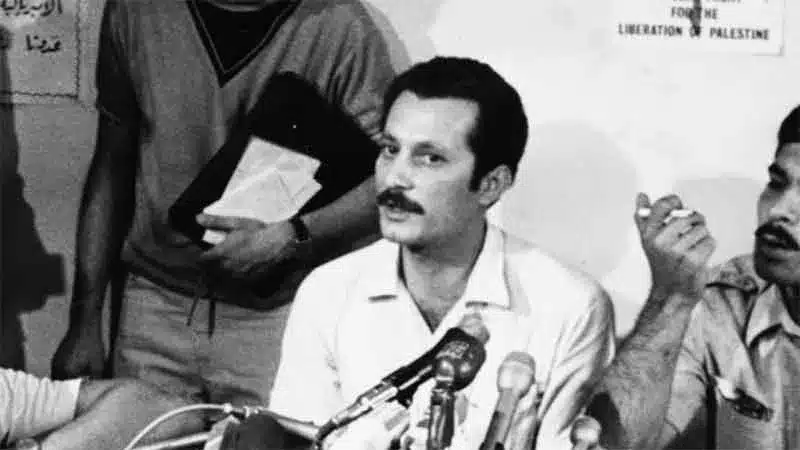

Ghassan Kanafani, Palestinian author and militant. Photo: Counter Punch.org/file photo.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

Ghassan Kanafani, Palestinian author and militant. Photo: Counter Punch.org/file photo.

By C Sétanta – Sep 22, 2025

The Gaza-led resistance to the Zionist entity’s genocidal war on the Strip and expansionist belligerence across a wider region has maintained threads of hope that the imperialist-backed occupation of Palestine can be defeated. Adjoined by armed reprisals from Yemen and, significantly, Iran, the current phase of the Palestinian national liberation movement against the bloody slaughter has precipitated a sea-change, with discomfort and division developing among Zionism’s western backers.

Movements since and before 7 October 2023 have also fuelled an intellectual fightback, with new generations seeking answers. In colonised Palestine and beyond, the search for a serious framework for understanding these historic events have led many back to the works of Ghassan Kanafani, the Marxist leader, novelist, artist and newspaper editor martyred along with his niece Lamis at the hands of the Israeli Mossad in Beirut on 8 July 1972, at just 36 years old. Today, Kanafani’s prognosis on the vanguard role of armed resistance is borne out daily in Gaza, while other aspects of his outstanding contribution offer prophecies and analyses ripe to quench a region and world hungry for change. But, as with other exemplary revolutionary figures, from Marx to Fanon, Guevara to Kahlo, Kanafani’s legacy is seized upon by forces seeking to muddy the waters, dilute and pacify its transformative potential.

A legacy of resistance literature

So what is the legacy of this multifaceted Palestinian intellectual? Justifiably, many have focused on Kanafani’s work as a novelist, with evidence suggesting that his storytelling began prodigiously, writing stories in Damascus as a teenager before becoming an acclaimed figure with 1963’s Men in the Sun, the first of four novels published in his lifetime. Kanafani would point to two foundational strands in his development: his eyewitness view of the Palestinian refugee experience, seeing figures like Umm Saad as “schools” for understanding the world; and his mid-1950s recruitment to activism via the Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM), founded by George Habash and others in 1951. Kanafani worked on the organisation’s publications from 1955 and it would be no exaggeration to describe him as an ANM writer in the years to follow, where he produced politically-conscious stories alongside fictional writing, with both aspects of his writing having direction from the ANM leadership.

The more deeply Kanafani became involved in politics, via the ANM and its Palestinian successor from 1967, the Marxist-Leninist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), the more his political journalism and analysis grew in volume compared to his fictional work. His account of a 1965 journey to communist China as a writer for the ANM’s al-Muharrir paper and editor of its Falastin pullout covered 150 pages, for instance, while his fictional works of the same year amounted to four short stories. In this work, his embrace of scientific socialism became even more apparent, but it was with the PFLP that Kanafani shone most brightly as a Marxist theoretician and organisational heavyweight. He wrote or contributed to epoch-defining pamphlets like the Political and Organisational Strategy (1969) and The Resistance and its Challenges (1970), and intervened decisively in factional debates, as in the 1972 PFLP congress in Baddawi camp, Lebanon, where his majority position won out against an ultra-left split.

Kanafani’s theoretical contributions over a period of little over a decade included many points that have caused his works to stand the test of time: coining the term “resistance literature” to describe the collective Palestinian effort to confront an oppressive and racist entity; understanding Zionism as an outpost of western imperialism in the region and seeing the anti-imperialist struggle as key to defeating Zionist colonialism; offering a materialist lens to grasp the experience of the 1936-39 revolt, with vital lessons for the coming movements; offering a stinging critique of Arab bourgeoisies after 1967, including the Palestinian strata which sought compromise with the occupation; applying to Palestine Mao’s critique of class collaborationism in the national liberation movement; championing the school of guerrilla warfare developed in Vietnam; and laying the groundwork for a principled boycott of the Zionist state and its backers. Collectively shaped in an environment of democratic centralism and revolutionary anger, these points and others formed the outlook of the PFLP, underpinning its then pivotal position in the Palestinian armed struggle.

Kanafani studies: a new wave

In a sense, Kanafani has been ever-present among Palestinians. His name and image on the walls of the camps, and projects like the network of kindergartens run by his wife Anni and the Ghassan Kanafani Cultural Foundation in Lebanon. But, aside from novels like Men in the Sun and Returning to Haifa, known by activists and academics alike, Kanafani’s deeper political contribution eluded even the most committed forces internationally. This changed with the reemergence of Kanafani’s work internationally, including the 2017 unearthing of a remarkable interview with Australian journalist Richard Carleton, where Kanafani the PFLP spokesman appears as the unflinching defender of the principles of Palestinian self determination. Implications of an equally-sided “conflict” where enemies could “just talk” were blown to smithereens, and the right to resist “to the last drop of blood” was sacrosanct. Spurred by the rediscovery of Kanafani, new English translations were published, including On Zionist Literature (Ebb, 2022), The 1936-39 Revolution in Palestine (1804 Books, 2023) and a collection, Selected Political Writings (Pluto, 2024).

With these books attracting fertile audiences and Kanafani videos circulating online amidst an epochal struggle between Palestinian resistance and a rabid, merciless occupation, the field of “Kanafani studies” – coined by editors of the Pluto volume, Brehony and Hamdi (Kanafani, 2024 px) – has rightly found new adherents. However, it is equally true that the Kanafani legacy, like that of other historical revolutionary theorists, has been seized upon by forces in politics and academia which seek to misappropriate and revise the essential features of his discourse. These have ranged from use of Kanafani’s name by organs of the Palestinian Authority to academic analyses, baselessly casting his commitment to the PFLP’s Marxism-Leninism and armed struggle into doubt. The practices attached to an almost total focus on Kanafani’s fictional writing – and their manipulation and misappropriation – are applied by often rather experienced academics who know and ignore Kanafani’s writing for the Front and its predecessor, the ANM.

This industry in academic obfuscation boasts a number of active exponents, in part explaining the astonishing silence of over a half-century witnessed upon the martyr’s political writing in the West. Based at the University of Kent, Bashir Abu Manneh poses as a Kanafani expert while attacking anti-imperialism in Syria and Palestine. In an insult to both figures, he writes that “Kanafani is the one Palestinian writer who had the makings of a Fanon.” (2016, p71; emphasis added). While he notes the value seen by Kanafani in progressive, anticolonial nationalism, the PFLP is almost totally absence from Abu Manneh’s narrative, where Kanafani is seen as holding “humanist” values “jarring” with commitment to the armed struggle (p77), but certainly not as a Marxist committed to the resistance of an armed vanguard. Again, no evidence is offered for this assertion. Meanwhile, the huge volume of political writing Kanafani produced for the organisation is ignored by Abu Manneh. Why? Again we find answers in the contemporary positions taken by the writer, which blame the resistance (of which the PFLP is a part) for the destruction of Gaza (Abu Manneh, 2024), oppose Palestinian rocket fire, and call for a two-state solution.

Abu Manneh’s comrade and British army collaborator Gilbert Achcar also poses as a scientific socialist. In a diatribe again homing in on Syria and Hezbollah, and “Stalinism” to boot, Achcar uses the dubiously-given platform of introducing a translation of the works of the great Lebanese socialist Mahdi Amel to refer to Amel and Samir Amin as the Arab world’s only two recognisable Marxists (2021, pix). Achcar was funded directly by the British government’s secretive Defence Cultural Specialist Unit (DCSU), which recruited agents in the world of academia to provide imperialist forces with cultural and historical education useful to their military interventions in and beyond the Arab world (Scripps 2019). Having backed the 2011 Nato war and slaughter in Libya, we should not be surprised at Achcar’s collaborationist role – though the openness to his contributions by platforms ranging from the Journal of Palestine Studies to the Historical Materialism conference should raise eyebrows around their own principles. Though he works for the British imperialist Ministry of Defence and attacks the Gaza resistance, Achcar would doubtlessly like to add his own name to this list of “Marxists.” The very idea that Kanafani had a Marxist theoretical contribution at all is anathema to a pro-imperialist cabal which supported “revolution” in Syria but attacks the armed resistance in Gaza.

Among a younger generation of scholars laying claim to the Kanafani legacy, translator of the recent 1936-39 pamphlet Hazem Jamjoum has appeared on a number of platforms. Jamjoum offered an rambling exposition of what he saw as Kanafani’s main contributions at a book launch hosted by the Jerusalem Fund and Palestine Center on 14 September 2023. The discussion was littered with such a litany of baseless assertions that a response is necessary to offer clarity for those looking for an accurate reflection of Kanafani; this particularly important in light of the translator’s own political standpoint, which prejudices the act of translation itself – more on this shortly.

During the discussion in question, Jamjoum made a series of claims on Kanafani’s relationship to the PFLP. Firstly, that when Kanafani was editor of the Front’s official organ al-Hadaf, “He didn’t agree with half of what he published,” but acted rather to “enable” other writers, “because the revolution would be stronger if these things were on paper.” In this view, therefore, Kanafani appears a politically-detached functionary, holding private positions totally at odds with his organisation. An anarchist renegade operating within the Marxist-Leninist vanguard.

The founding slogan of al-Hadaf newspaper, “all truth to the masses,” is erroneously attributed by Jamjoum to Kanafani, though it came from Wadi’ Haddad. Jamjoum claims that this slogan and Kanafani’s approach as editor “runs counter to any kind of vanguardism.” From a depiction of Kanafani as a mere “enabler” of ideas with which he may or may not have agreed, Jamjoum tells us that Kanafani was against the foundational fabric of his organisation, despite Kanafani writing under the banner of “the view of the PFLP” that the group constituted a “vanguard grouping in the armed resistance movement” (Kanafani 2024, p124). Jamjoum’s standpoint must also assume that Kanafani’s own arguments on the vanguard are (somehow) the opposite of what he really thought (but did not say or write).

In a May 2025 interview published in Mondoweiss, Jamjoum is asked about how the 1936-39 revolt is perceived in the current Arab context. While correctly pointing out how existing Arab states have no interest in their populations having knowledge of this earlier period, Jamjoum’s one example is curious:

“Think of the Asad regime and how much lipservice it paid to Palestine as an abstract cause, then compare that to how it directly or indirectly obliterated Palestinian refugee camps from Tal al-Zaatar to al-Yarmouk.”

This disingenuous statement comes six months on from a sectarian coup in Syria led by former ISIS and al-Qaeda leaders, backed by all major imperialist powers and enabled in the first place by Zionist bombing of Syrian state infrastructure. The Jolani regime in Damascus has normalised Zionist occupation and is backed overwhelming by Arab regimes which have sided with imperialism throughout the genocide on Gaza; among them, Saudi Arabia has banned Kanafani’s books. The “Asad regime” did not. Along with the further Zionist encroachment and expansion of sectarian killings in the aftermath of the coup, Palestinian resistance organisations have faced direct attack, including the internment of PIJ and PFLP-GC leaders. The Jolani junta was totally silent as the Zionist entity bombed Iran in June 2025.

This silence has clear recent context. At a time of increasing US and European imperialist involvement in the Syria war, with the opposition to the Baathist government clearly comprising a collection of Turkish- and Gulf-backed fascist extremists, sections of the opportunist left maintained the lie that these forces were “revolutionary.” Jamjoum signed a 2016 statement organised by right opportunist and Ukraine government supporter Joey Ayoub, blaming Asad for the country’s destruction, supporting the “revolution” (of unnamed “revolutionaries”) and railing against leftist critique of the flow of foreign funds to Syrian groups. Anathema to these opportunist forces is the idea that Baathist Syria was a complex but independent state which did create space for Palestinian organisation, for which it earned praise from PFLP founder George Habash, among others.

Why is this important to our discussion of Kanafani? In his Jerusalem Fund book talk, Jamjoum says:

“[Kanafani] strays from the party line – that was then. And he definitely strays from the party line today in terms of what was reached. So there is a vested interest in the part of the political terrain that is supposed to be his side in not actually engaging that part of his approach, analysis, writing… The rest of Ghassan is left out and we only have Ghassan the ideologue… To assume he is like them [PFLP]… you are actually wrong in this assumption.”

Which party line did Kanafani “stray from” during his years in ideological leadership of the Front? In the absence of any evidence, we remain in the dubious realm of conspiracy and speculation. Furthermore, Jamjoum brings his time machine to the occasion, to cast aspersions and claim that Kanafani would have been even more bitterly opposed to “what was reached” in PFLP policy. Does he mean the Front’s opposition to imperialist intervention in Syria under the guise of a mythical “revolution”? Is the implication that Kanafani would have left the PFLP or would have held an opposing view to its leaders, from Ahmad Saadat to Leila Khaled? We are encouraged only to speculate. We are not told what half of the articles published in al-Hadaf Kanafani supposedly agreed or disagreed on, nor are any sources offered by Jamjoum. The reason for this is that there are no truth in Jamjoum’s claims whatsoever.

Revising a revolutionary classic

Do Jamjoum’s political statements have any bearing on his translation of the 1936-39 text, which won a gong at the prestigious Palestine Book Awards in London in 2024? It should be mentioned that the new publication was, in fact, a re-translation. An original English translation of The 1936-39 Revolt in Palestine was published by the PFLP central media committee in 1972 and appeared on the pages of the PFLP Bulletin, circulated by the organisation’s supporters among solidarity circles internationally. Charlotte Kates writes:

“The Bulletin, distributed around the world in the 1970s through local supporters as well as direct mail, spoke to a global audience engaged in revolutionary action and anti-colonial struggle. This was a time when the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon were centers of global organization and action, and when revolutionary movements in the imperial core were directly engaged with Palestinian revolutionary organizations, particularly the PFLP, in popular and armed struggle alike.” (Kates, 2024)

The Revolt pamphlet served as a classic educational analysis and was disseminated in leftist circles internationally, including by the New York-based Committee for a Democratic Palestine, which published a widely-distributed version of the PFLP translation. Perhaps unfairly given that the translation was actually an English version, interpreted politically for Anglophone activists, the 1972 Revolt pamphlet was deemed by some to be a poor translation. The central media committee of the PFLP, of which Kanafani was a leading member, had added certain explanatory phrases and carefully chosen its emphasis of particular arguments in line with what the organisation saw as the priorities of international action in solidarity with the resistance. The 1804 Books version, however, sought to address the pamphlet’s perceived translation deficiencies.

But choosing Jamjoum as translator brought its own problems. Comparing the text with the original Arabic and PFLP translation, we find a blunting of certain phrases. When Kanafani paraphrases George Mansur, he refers to “Jewish (im)migration” (al-hijra al-yehudiyya, p386), while Jamjoum translates this as “Zionist immigration” (p8) or refers to an “influx of migration,” omitting the word “Jewish” (Kanafani 2015, p382/Jamjoum p5). At a time when Zionists attempt to smear pro-Palestine activists as antisemitic, this translation retreats from recognising the Jewish supremacist reality which took hold under British imperialist tutelage.

From Ghassan Kanafani to Walid Daqqah: Assassination, Imperialism, Resistance and Revolution

Arguably more concerning, however, is the inconsistency with which Jamjoum deals with the question of national liberation. At certain points in the text, he correctly translates al-haraka al-watanuiyya al-Filastiniyya as “the Palestinian nationalist movement” (p381/p3) or “Palestinian national movement” (p397/p17), but word choices elsewhere seem to skew Kanafani and reproduce Jamjoum’s own politics. The most serious case is the translation of an important phrase in the pamphlet’s introduction that clearly means “the Palestinian nationalist (or national) struggle” (al-nidal al-wataniyya al-Filastini) as “the Palestinian struggle for freedom” (p380/p2). The original 1972 translation reads:

“The traditional leadership… participated in, or at least tolerated, a most advanced form of political action (armed struggle); it raised progressive slogans, and had ultimately, despite its reactionary nature, provided positive leadership during a critical phase of the Palestinian nationalist struggle.”

To the PFLP central media committee, the organ which produced the original translation and of which Kanafani was a leading member, nationalism or nationalist were not dirty words, and are utilised no less than 53 times during its English version. Jamjoum, however, selects the terms sparingly, and frequently uses “patriotic” as a descriptor of the Palestinian and Arab movements. This weakens the thrust of phrases translated in the original Anglophone version and which clearly demarcate the Palestinian and Arab struggles as movements for national liberation, rather than having vague patriotic content.

If translation is an act of creative interpretation, then why is this discussion important? Statements on this subject by the translator since the pamphlet’s release again offer intrigue, in ways that seek to further rewrite the script on Kanafani’s politics. In the book launch discussion drawn upon above, Jamjoum states that, “When someone makes out Kanafani to be a nationalist, you’re completely missing the point.” Like Jamjoum’s other interjections, little backing is offered to this statement, amounting to a mere assertion that Kanafani operated at a distance to nationalism in the Arab and Palestinian struggles. In the 1971 film Revolution Why? Kanafani speaks in English and puts the question succinctly:

“The question of Palestine is the question of a clashing contradiction, between the national liberation movement of the Arabs, headed by the Palestinian national liberation movement, and imperialism in this part of the world, headed by the Zionist movement.”

Shortly before, he wrote:

“[I]t is apparent that there is no guide to action clearer and more effective than Marxism–Leninism, fused creatively with the militant coherence of Arab nationalism.” (Kanafani 2024, p158)

If we were to translate the word wataniyya in this excerpt as “patriotism”, we would be wildly missing the point. Moreover, the blanket rejection that Kanafani was any kind of nationalist appears designed to miss the point. Kanafani had been a member of the Arab Nationalist Movement, which later became the PFLP. Both organisations held broader Arab liberation as being key to defeating colonialism in Palestine, and retained the principles of the most advanced forms of the nationalism of the oppressed, as witnessed at the high points of struggle in Egypt, Yemen, Iraq and elsewhere. Kanafani remained firm in his belief in national liberation and saw Marxism as being linked to a progressive Arab nationalism. While it would be a mistake to delink the Marxism of Kanafani and the PFLP from nationalism, in the same liberationist, proletarian sense seen in Vietnam, Cuba or China, it would equally be a distortion to delink the national element from their socialist outlook. In these revolutionary victories, Kanafani derived the “militant coherence” he saw as shining the path of Palestinian liberation. Louis Allday writes that, ‘Although the formation of the PFLP in 1967 is often portrayed as Kanafani and Habash rejecting Pan-Arabism wholesale in favour of Marxism-Leninism,’ neither they nor their organisation retreated from seeing Palestinian liberation as having direct significance to others in the region, and came to ‘understand the Palestinian cause as indivisibly linked to a broader Arab struggle.’ (Allday 2023)

Though there are exceptions in the movements drawing on Kanafani’s work to build principled anti-imperialist opposition to rapacious Zionism, the academic world is teeming with further examples of distortion. Kanafani and the PFLP are variously seen as being at odds with “classical Marxism” and “self-emancipation” (Lavalette 2020, p60) or as having little or no relevance to his organisation at all. The latter position is represented by Leopardi, whose 296-page book attacking the Front makes only one reference to Kanafani, as “official party mouthpiece” (2020, p11), suggesting confluence with the assertions of Abu Manneh and Jamjoum.

Uncoupling Kanafani from his organisation and the liberationist brand of Marxism it developed after 1967 amounts only to revisionist sabotage. The broader claims made by these academics are significant on a number of levels. Firstly, they drive an ideological wedge between the PFLP and its leading intellectual figure. Kanafani’s agency as official spokesperson, editor and writer of official, publicly shared documents is thrown into intrigue, with the totally unsubstantiated assertion that Kanafani was a dissident against his organisation. Secondly, the democratic centralism through which Kanafani operated is seen as subterfuge for ulterior, unspoken motives which Jamjoum and others are unable to identify, let alone prove. Kanafani is seen in these revisionist accounts as a sort of anarchist rebel to the organisation, despite his decorated and respected standing, and the real role he played in debates, theorising and position-shaping. Kanafani argued directly for the kind of vanguard organisation that brought victory in Vietnam and played a central role in the way the PFLP came to see itself as the Palestinian national liberation movement entered an impasse in the early 1970s.

Perhaps the most fitting description of Kanafani’s value to the movement comes from Marwan Abd el-‘Al, a leader of the PFLP in Lebanon:

“It is important to note that Ghassan was not a member of the Political Bureau – and was not appointed until after his martyrdom – but was a member of the Central Media Committee. But the fact that his writings were released by the Central Committee offers an important indication that he acted as an unofficial member of this leadership body, and that the work of Ghassan occupied the highest position in the politics of the Front. An intellectual with such thought, experience, and character could shape the minds of others. To me, this is more dangerous to Israel than any nuclear weapon.”

Conclusions

Discussing the lengths by which European propaganda had gone to in order to superimpose the Zionist entity over an ethnically-cleansed Palestine, Kanafani warned that the distorting of historical facts “is one of the pillars of Israeli media hegemony” (Kanafani 2024, p213). Standing for Palestinian liberation today means combating the historic and contemporary distortion of facts and narratives like never before. Kanafani was no rebel to the ideological programme of the organisation he helped to lead. He was cut from its cloth and in turn enriched the Front through his unparalleled Marxist contribution, his vast experience as a writer and polemicist, and his decisive interventions in both internal and external debates. Made a member of the PFLP’s political bureau upon his martyrdom, Kanafani was already leading the Front intellectually, such that George Habash lamented the “really painful hit” inflicted upon the organisation with his loss. (Kanafani 2024, 9). One great revolutionary afflicted by the demise of another, his comrade.

It is befitting to conclude this essay with an important caveat: if we do, indeed, see “Kanafani studies” as a serious and timeworthy effort, then this “field” must also, surely, be constitutive of many approaches, modes of analyses and debates. While we have focused to some degree on the presence of Kanafani in anglophone writing, the latter is already true to a significant degree in the most radical contemporary arenas of Arabic literature, including elongated al-Hadaf specials published by Kanafani’s PFLP comrades of today, and in the biting critiques of anti-imperialist radicals like the late, Lebanese editor of the al-Adab journal, Samah Idriss. Such is the multi-pronged attack by which Ghassan Kanafani tackled the beasts of imperialism, Zionism and Arab reaction (through writing, speaking, drawing…) that his legacy demands rigorous study and allegiance to the resistance if we are ever to consider ourselves as revolutionaries worthy of his example.

References

Abd el-‘Al, Marwan. “Palestinians in Lebanon and the “Political Ghassan Kanafani”: An Interview with Marwan Abd el-‘Al, PFLP.” Arab Studies Quarterly, Volume 36, Issues 3-4, September 2024.

Abu Manneh, Bashir.

Allday, Louis. ““A Race Against Time”: The life and death of Ghassan Kanafani.” Mondoweiss, 11 September 2023.

Amel, Mahdi. Arab Marxism and National Liberation. Brill, 2021

Ghazi, Christian. Resistance Why? [Film]. Fifth June Society, 1971.

Kanafani, Ghassan.

Kates, Charlotte. “Kanafani’s 1936–1939 Revolt in Palestine: A Revolutionary History.” Arab Studies Quarterly, Volume 36, Issues 3-4, September 2024.

Lavalette, Michael. Palestinian Cultures of Resistance: Mahmood Darwash, Fadwa Tuqan, Ghassan Kanafani, Naji Al Ali. Redwords, 2020.

Leopardi, Francesco Saverio. The Palestinian Left and Its Decline. Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

Scripps, Thomas. “Leading Pabloite Gilbert Achcar provided counter-insurgency advice to British Army,” World Socialist Website, 9 August 2019.

C Sétanta is a writer and activist living between Europe and the Middle East.