The Construction of Guaido: Narrative of the Antichavista D-Day

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

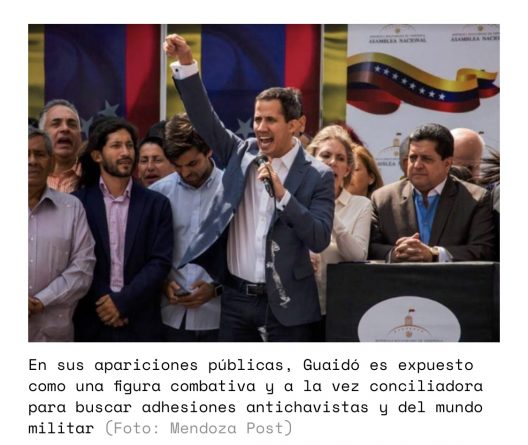

For the effects of the destabilization roadmap of Venezuela through external pressures and the proclamation of a paragovernmental figure to submit to a new cycle of instability for Venezuelan institutions, the presentation of the the figure of Juan Guaidó and his calls for new mobilizations against Chavismo have indisputable elements of fabrication that are necessary to analyze.

From an overview, the distinguishable elements of the narrative about Guaidó can be summarized as follows:

#Noticias| Esposa de Juan Guaido envía mensaje a familiares de la Fuerza Armada Nacional #21ene Parte 2 pic.twitter.com/dZi8yA7N3W

— LLanero Digital VE (@LlaneroDigitalV) January 22, 2019

#Venezuela inició el año en silencio de lejanía, pero en cada Cabildo se oye una nueva esperanza. Con el retumbar del #Cacerolazo del Oeste al Este de Caracas, se hace inevitable que el grito sea un estruendo por el cambio.

¡Vamos a reencontrarnos este #23E!— Juan Guaidó (@jguaido) January 22, 2019

<li></li><strong>NARRATIVE RESOURCES OF THE CALL AND OTHER ELEMENTS</strong>

Once again triumphalism and promises of Maduro’s removal from power come back to the table to mobilize opposition supporters. It is a cycle that has already been reproduced at the beginning of the year in 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017.

The Venezuelan opposition deals with a considerable decline in its base of support and partial decline in the willingness of its followers to sign another mobilization agenda against the Venezuelan government that will probably end up in violence and without concrete results in sight. In simultaneous with an important migratory process of a part of the followers of the opposition with a tendency to exasperating antichavista fanaticism.

In view of this, the presentation of the “motive” for the mobilization lies this year in the external support for a transition in Venezuela and the removal of President Maduro through pressures, sanctions, siege and the threat of an intervention to bring to power Juan Guaidó as leader “representative of popular aspiration”.

The antichavismo calls and instrumentalizes the situation of important social strata dealing with the economic discontent, and this is supported by a dramatic acceleration of the inflationary elements that shot up at the beginning of the year. Inflation by means of a parallel dollar and a disproportionate rise in prices preceded January 10 and are fuel for raising the “exit to the street” of the population on January 23. This gives the anti-chavista narrative a character of “popular struggle” for the economic situation, although this is clearly induced in the context of war.

Simultaneously, the opposition uses other resources to summon in slogans such as: “take out Maduro so that those who migrated return”, “allow the entry of humanitarian aid”, “the exit is through a military coup with popular support”, “it is necessary the intervention of Venezuela. ” Thus, in an apparently popular speech, they amalgamate a “feeling of rejection and necessary response” against the Venezuelan institutions. An element of clear fabrication during years of total spectrum siege against the country.

In social networks and digital media, the “words and symbol images” of rampant violence aimed at Chavismo are becoming more and more virulent and consistent. As a preparation of subjectivity for new situations, this time, applauded by foreign pressure and internal and external military threat. This year the narrative has the distinctive element of “defending the installation of the transitory government” and the proclamation of Guaidó as “legitimate president”.

Translated by JRE/AR

.