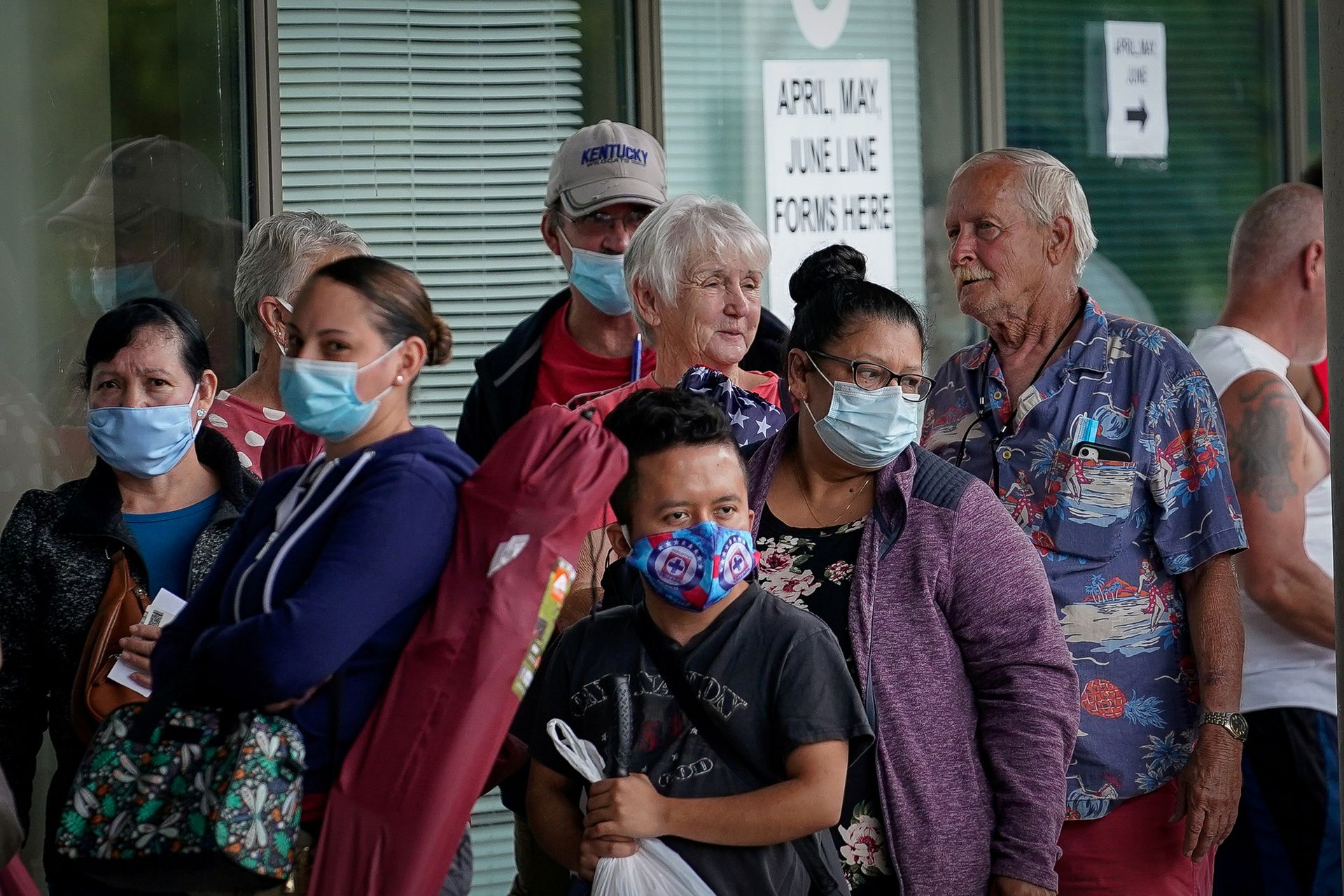

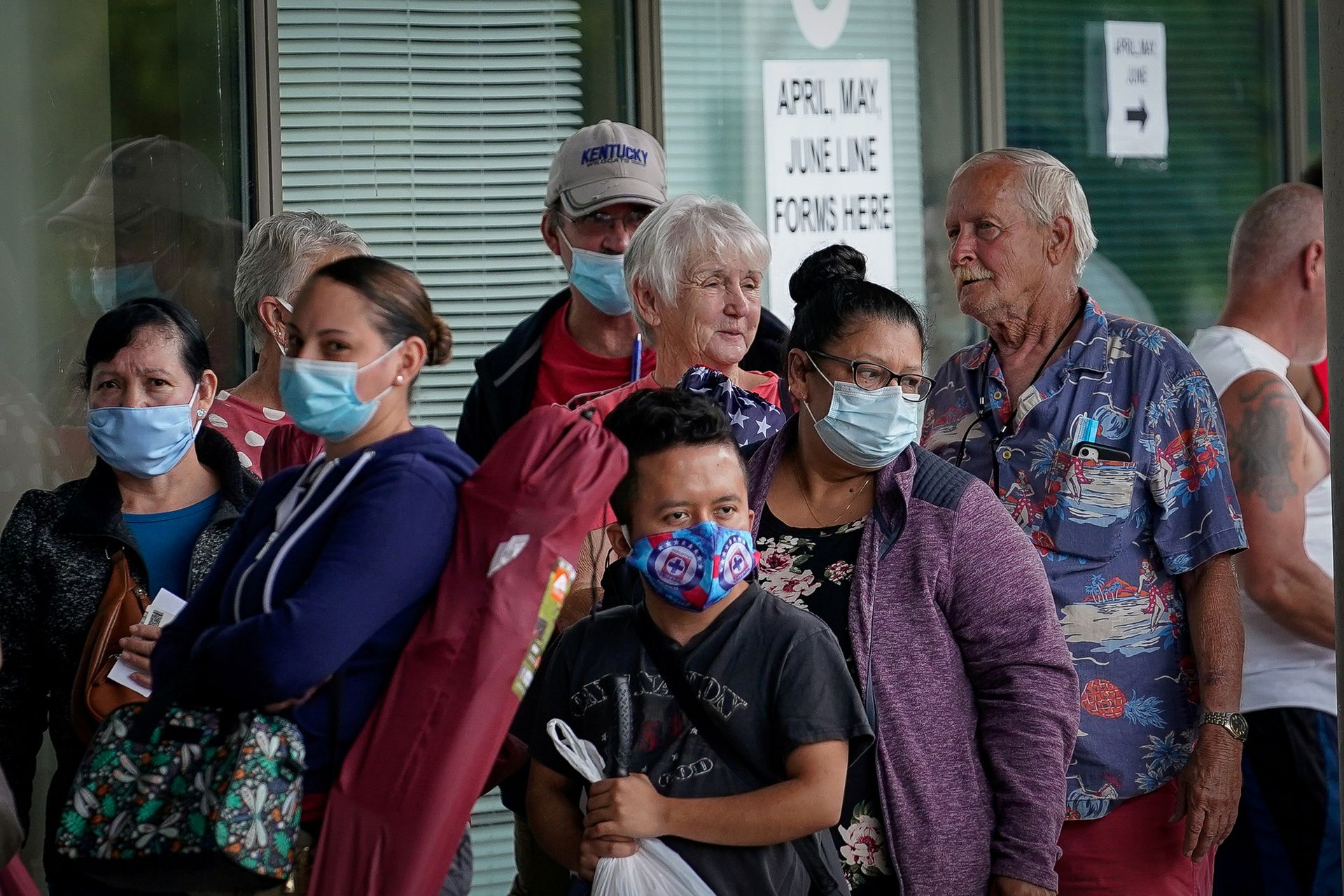

Masked adults line up outside a career center in Kentucky, US, hoping to find assistance with their unemployment claims. Photo: Reuters/Bryan Woolston.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

Masked adults line up outside a career center in Kentucky, US, hoping to find assistance with their unemployment claims. Photo: Reuters/Bryan Woolston.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) managing director Kristalina Georgieva has now openly admitted that the year 2023 will witness the slowing down of the world economy to a point where as much as one-third of the world will see an actual contraction in gross domestic product. This is because all three major economic powers in the world—the US, the European Union, and China—will witness slowdowns, the last of these because of the renewed Covid upsurge. Georgieva claims that of the three, the US will perform relatively better than the other two because of the resilience of its labor market, providing some hope for the world economy as a whole.

There are two ironic elements in Georgieva’s remarks. The first is the IMF’s admission that the best prospects for the world economy today lie in the stabilization of workers’ incomes in the US. For an institution that has systematically advocated cuts in wages, whether in the form of remunerations or social security wages, as an essential part of its stabilization-cum-structural adjustment policies, this is a surprising—though welcome—admission.

Of course, Georgieva, many would argue, sees US labor market resilience as the result of the US’s economic performance and not as a cause of the US’s relatively good economic prospects. But her considering it a “blessing” (though not an unmixed one for reasons we shall soon see) undoubtedly counts as recognition of the demand-sustaining role of workers’ incomes.

Some may argue that the stabilization-cum-structural adjustment policies of the IMF are typically meant for economies that are in crisis as a means of overcoming such a crisis, not as a panacea for growth, so seeing a change in the IMF’s understanding in this regard may be unwarranted.

But what the IMF is now saying is certainly out of line with what it usually says; it is in effect admitting that a resilient labor market in the US is beneficial for economic growth, which begs the question: why should other economies too not attempt to support resilient labor markets even when they are in crisis, and tackle their crises through other more direct means, like import restrictions and price controls? Admitting that the resilience of the US labor market benefits its economy, and hence the world economy as a whole, thus fundamentally runs counter to what the IMF generally stands for, at least in current neoliberal times.

The second ironic element in her remarks is her recognition that such a resilient labor market, while being beneficial for US growth, will simultaneously keep up the inflation rate in the US, forcing the Federal Reserve Board to raise interest rates further.

This has two clear implications. First, it means that the US growth rate, while being less affected for the time being, will inevitably be constricted in the months to come as the Fed raises the interest rate. The US performing relatively better in 2023 is thus not a phenomenon that will last long. Since any poor performance by the US will have an adverse effect on the world economy as a whole, this amounts to saying that world recession will worsen in the months to come, unless China’s Covid situation improves substantially.

In other words, it is like saying that even if 2023 will only see a third of the world economy facing recession, a much larger swath of it will fall victim to recession later. This certainly is the most dire prediction made about the prospects of world capitalism at the present juncture by any major spokesperson of it.

The World Bank, too, has been warning of a serious recession looming over the capitalist world and discussing in particular its implications for third world economies. In September 2022, it put out a paper predicting a 1.9% growth for the world economy in 2023. But both the IMF and World Bank attribute the looming recession primarily to the Ukraine war and the inflation it has given rise to (and also in passing to the pandemic); the response to that inflation in the form of an all-round increase in interest rates is what underlies the current threat of recession. There is no recognition by these institutions of any problem arising from the neoliberal economy that could be exacerbating the looming crisis.

This analysis, first of all, is erroneous. Long before the Ukraine war, inflation had reared its head as the world economy had started recovering from the pandemic. At that time, such inflation had been attributed to the disruption in supply chains caused by the pandemic, though many had criticized this analysis even then. They pointed out that, more than any actual disruption, the inflationary upsurge owed much to the jacking up of profit-margins by large corporations in anticipation of shortages. The Ukraine war occurred against this backdrop of ongoing inflation and added to it quite gratuitously, as the Western powers imposed sanctions against Russia.

No Russian Roulette: The Hunger Emergency and the Global Corporate System

A look at the movement of crude oil prices confirms that the Ukraine war is not the genesis of the inflationary upsurge. The rise in Brent crude prices occurred primarily in 2021 as the world economy started recovering from the pandemic: the rise between the beginning of 2021 and the end of that year was by more than 50%, from $50.37 per barrel to $77.24 per barrel; the corresponding rise in 2022, during which the Ukraine war occurred, was from $78.25 to $82.82, i.e. by 5.8%, which is less than the current inflation rate in most advanced capitalist countries, even though inflation is generally assumed to be driven by oil prices.

True, immediately after the imposition of sanctions against Russia, world oil prices shot up, reaching a high of $133.18 per barrel during 2022, but then came down quite sharply, so simply blaming the Ukraine war for the price hike is not only misleading (as it is not the war per se, but the sanctions that influenced the prices) but also erroneous (as prices should have come down when the hike induced by the sanctions abated).

It is not only the analyses of the Bretton Woods institutions that is flawed. Even more noteworthy is the fact that they have no prognosis whatsoever, even within the terms of their own analyses, of how this world recession is going to end. If, as they believe, it is the Ukraine war that is responsible for the looming recessionary crisis, then they should, at the very least, express hope for it to end swiftly. That, however, is unacceptable to Western imperialism, which wants the war to drag on so that Russia is “bled” into submission; this is why the twin institutions express no opinions on the need to end the war.

But even if they chose to remain silent on the question of ending the war, they could have made suggestions to tackle the inflationary crisis in some way other than by raising interest rates and unleashing a recession. The IMF and World Bank, however, are so committed to free markets that they cannot contemplate any other inflation control measure (such as direct price control), even as they lament the recessionary effects of interest rate hikes.

Likewise, even as the World Bank president David Malpass commiserates with debt-encumbered third world countries, which will be badly hit in the coming months, and even says that a large chunk of their debt-burden has emerged due to the high interest rates themselves, there is not a word in his speech in favor of lowering interest rates. Both of the Bretton Woods institutions, in other words, are rich in condolences but empty in concrete measures to help the world’s poor.

This is not just a symptom of cowardice. It points to something deeper: namely, the genuine impasse in which world capitalism finds itself today. If the structure of Western imperialism, as it has evolved over the years, is to be kept intact, then the metropolitan countries have to keep the Ukraine war going, in which case inflation at the current pace becomes unavoidable in the absence of an engineered recession and consequent unemployment. World capitalism choosing to embark on this route, therefore, should not cause any surprise; the point is to resist it.