Oil installations on Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela in 1935. Photo: Alamy.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

Oil installations on Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela in 1935. Photo: Alamy.

By Ana Maria Monjardino and John McEvoy – Feb 6, 2026

Declassified files expose how the UK has tried to control Venezuela’s oil for over a century, seeking to thwart nationalisation through political pressure, propaganda, and covert operations.

In October 2001, two years into his presidency, Hugo Chávez made a trip to London to meet with then UK prime minister Tony Blair and other high-level officials.

Official records detail how the Venezuelan president’s proposed Hydrocarbons Law, a major restructuring of Venezuela’s oil industry, was high on the British agenda.

The law aimed to assert sovereignty over Venezuela’s resources by mandating at least 50% state ownership in mixed enterprises and increasing royalties on foreign oil interests.

This was a serious cause for concern for Britain, whose main interests in Venezuela centred on Shell, BP, and BG Group’s investments in the oil and gas industry.

“British companies have over $4bn already invested” in Venezuela, noted one Foreign Office official, with new investments of another $3bn planned for the oil industry.

Blair was thus instructed by advisers to impress on Chávez that the UK government was “following your proposed hydrocarbons legislation very closely”.

In private, Blair’s adviser and future MI6 chief John Sawers wrote that “the only reason for seeing him is to benefit British oil and gas companies”.

Sawers’ note drove at the core issue which had been guiding Britain’s relations with Venezuela for over a century: oil.

Declassified has combed through dozens of files in the National Archives which expose how the UK government has repeatedly sought to thwart the nationalisation of oil in Venezuela since it was first discovered during the early twentieth century.

Working in partnership with Britain’s leading oil corporations, the Foreign Office has resorted to political pressure, propaganda activities, and covert operations to maintain control over Venezuela’s lucrative crude.

The origins of Britain’s interest in Venezuela’s oil

In 1912, Royal Dutch-Shell began operations in Venezuela and, two years later, the company – alongside US firm General Asphalt – discovered a petroleum field in the small town of Mene Grande.

George Bernard Reynolds, a geologist at Venezuelan Oil Concessions Limited (VOC), a Shell subsidiary, described the supplies as “enough to satisfy the most exacting”.

By 1920, the CIA reported that practically all of Venezuela’s oil production and its most promising concessions were held by Royal Dutch-Shell and two American companies, Jersey Standard (SOCNJ) and Gulf.

Indeed, Venezuelan oil controlled by Royal Dutch-Shell had increased by over 600% from 210,000 barrels in 1917 to 1,584,000 in 1921.

“Is there any other company more conclusively British than this”, asked Sir Marcus Samuel, chairman of the Shell Transport and Trading Company, in June 1915, “who have proved themselves more willing and able to serve the interests of the Empire?”

But foreign control over oil had serious consequences for Venezuela’s land and people.

In 1936, oil workers in Maracaibo called a general strike in response to low wages, poor living conditions and the association of oil firms with the late dictator, Juan Vicente Gómez. It lasted for 43 days, during which time oil production decreased by 39%.

In response, Venezuelan president General Eleazar López Contreras introduced a series of reforms to improve labour conditions.

This made him unpopular with the British and US oil executives, who were described by US ambassador Meredith Nicholson as belonging to “the old school of ‘imperialists’ who believed that might – in the business sense – was right”.

Venezuela’s oil nonetheless remained central to the British imperial project and, by the outbreak of World War Two, Venezuelan oil “took on particular significance within the British war effort as oil from the Middle East became less accessible following the closure of the Mediterranean in 1940”, according to research by academic Mark Seddon.

Officials therefore became increasingly worried about nationalisation in Latin America, particularly after foreign oil interests – including those of Shell – had been expropriated in Mexico in 1938.

That year, for instance, British diplomat John Balfour wrote: “We should do all we can to show that it is not in the interests of a Latin-American country like Mexico to eliminate British interests from participating in the exploitation of its oil resources”.

A dangerous opponent of capital

Concerns around nationalisation arose once again during the Rómulo Betancourt administration in the 1940s.

He was described by the Foreign Office in 1945 as “by far the most dangerous opponent of capital in Venezuela”, while the oil companies worried about his past support for communism.

These concerns proved overblown as Betancourt developed into a staunch anti-communist. According to a CIA file dated March 1948, Betancourt and his predecessor, Rómulo Gallegos, met to discuss “the proposed outlawing of the Communist Party in Venezuela.”

The first step, according to the document, “was the dismissal from the [oil workers union] Fedepetrol of all Communist Party petroleum syndicate delegates”.

Shell’s directors nonetheless responded positively to the military coup which toppled Betancourt in 1948.

They believed, as UK ambassador John H. Magowan noted in February 1949, that the new administration would “reverse the Betancourt tendency to hostility towards the ‘capitalists’ and ‘colonial’ powers”.

While US-owned SOCNJ had emerged as Venezuela’s main oil producer by this time, Shell remained the second most important player and, by 1950, the company had centralized its operations, building a modernist headquarters in northern Caracas.

The propaganda campaign

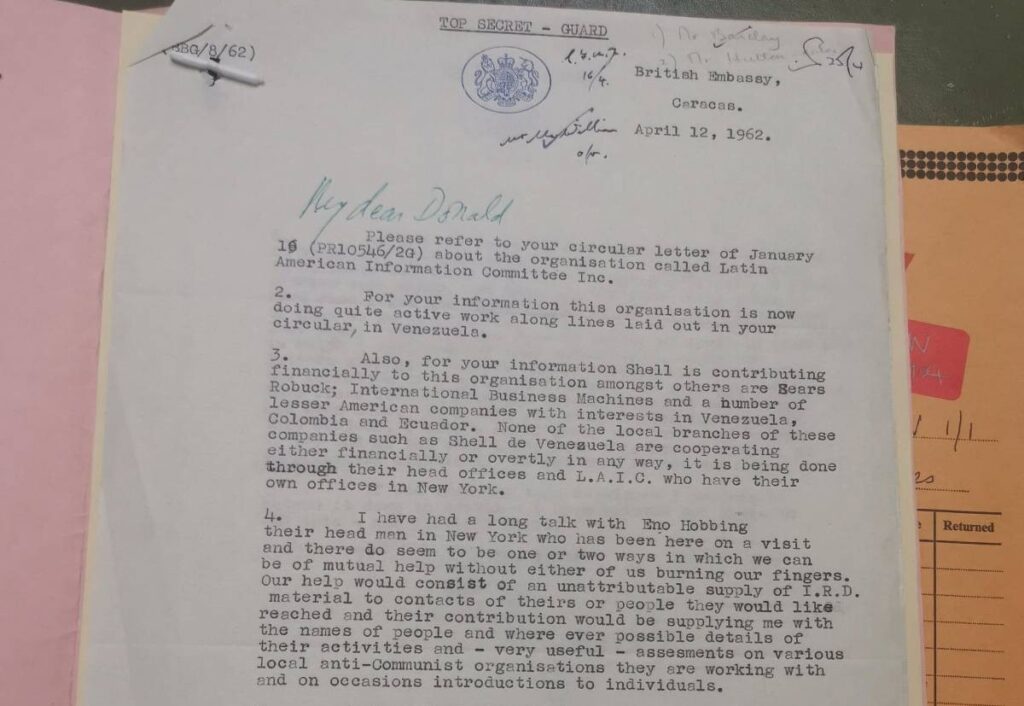

During the 1960s, as the shadow of the Cold War cast over Latin America, a propaganda unit within the Foreign Office secretly worked to protect Britain’s oil interests in Venezuela.

That unit, named the Information Research Department (IRD), had been set up in 1948 to collect information about communism and distribute it to contacts worldwide.

The goal was to build resilience against communist and other national liberation movements while cultivating foreign agents of influence such as journalists, politicians, military officers, and businessmen.

By 1961, the IRD viewed Venezuela as the third most important country in Latin America in light of the risk of left-wing “subversion” and Britain’s strategic stake in the country’s oil industry.

That year, the IRD worked with Britain’s intelligence services to promote a boycott of El Nacional, the largest newspaper in Venezuela, with the goal of forcing it “to abandon its campaign in favor of expropriating foreign companies and promoting communist agitation”.

The campaign not only had the backing of powerful conservative and anti-communist groups in Venezuela but also the foreign oil companies, who agreed to suspend their advertising in the newspaper.

By 1962, IRD officer Leslie Boas was able to boast that El Nacional had “changed its tone in a great way”, with the newspaper’s circulation also dropping from 70,000 to 45,000 per day.

Reactionary networks in Venezuela were also being covertly funded by Shell in this period, according to recently declassified files.

In April 1962, Boas wrote to IRD chief Donald Hopson about the Latin American Information Committee (LAIC) which was “now doing quite active work… in Venezuela”.

The first director of LAIC was Enno Hobbing, who divided his work between Time/Life magazine and the CIA and later played a role in Chile’s 1973 coup d’état.

Boas explained that he “had a long talk with Hobbing […] and there do seem to be one or two ways in which we can be of mutual help without either of us burning our fingers”.

Such help would include “an unattributable supply of IRD material to contacts” of LAIC in return for LAIC supplying Boas with access to and information about local anti-communist networks.

Remarkably, Boas disclosed that Shell was “contributing financially to” LAIC alongside US retailer Sears Roebuck and other “International Business Machines”.

He added that “none of the local branches of these companies such as Shell de Venezuela are cooperating either financially or overtly in any way, it is being done through their head offices and LAIC who have their own offices in New York”.

It was during this period that Shell and BP were also providing direct, “handsome” subsidies to the IRD to promote their oil interests across Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa.

Network of ‘Influencers’ Conspire to Threaten Venezuela’s Attorney General Saab

Nationalisation rekindled

The IRD continued to promote Britain’s oil interests in Venezuela through the 1960s and 1970s, until the unit was closed down in 1977.

In a country assessment sheet for Venezuela, dated 1969, an IRD official noted how “we have considerable investments in the country, particularly those of Shell, whose fixed installations alone have been conservatively valued at £300 million”.

The official continued: “Shell’s operations in Venezuela play an important role in the company’s very substantial contribution in invisibles [earnings through intangible assets] to our balance of payments”, noting that Britain’s key objective was therefore “to protect our investments”.

Two years later, IRD field officer Ian Knight Smith wrote to London with concerns about how “the emotional issue of economic nationalism, always a potent force in a country whose main natural resources are largely in the hands of foreign companies, was [being] rekindled”.

Worse still, the Venezuelan president, Rafael Caldera, had “made his own contribution to the new nationalism – in the shape of a law nationalising all natural gas deposits”.

The IRD consequently prepared briefings “on communist instigation of charges against the international oil companies” to be shared with contacts across Venezuela.

In addition, the propaganda unit “cast around for material with which to brief IRD contacts who are in a position to influence government policy or legislation affecting foreign investments in Venezuela”.

Officials were particularly interested in commissioning a “well-researched paper on the positive aspects of foreign investment in developing countries, helping to counter the growing assumption, carefully fostered by the extreme left, that all foreign investment is basically suspect”.

It was within this context that the Foreign Office privately advised that “we should protect as far as we are able Shell’s continued access to Venezuelan oil”.

Share of the gravy

For all its efforts, the IRD was not able to turn the tide of nationalisation in Venezuela, with plans developed during the 1970s for the early reversion of foreign oil interests to the state.

Venezuelan oil was officially nationalised in 1976, with foreign companies including Shell being replaced by the state-owned Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA).

But this was by no means the end of the road for Britain’s oil interests in Venezuela.

In a background briefing for a visit by Venezuelan president Carlos Andrés Pérez, dated November 1977, the Foreign Office observed that “Shell is still our largest single interest”.

The official added: “It should not be forgotten that despite nationalisation our largest commercial stake in this country is still Shell, and although they no longer, since nationalisation, produce oil here, they earn millions of dollars from their service and marketing contracts with their former company”.

The company also continued “to off-take very large volumes of Venezuelan oil for sale mostly in the US and Canada”.

Another official remarked upon the “furious activity of all European countries, including ourselves, in trying to get our share of Venezuela’s economic gravy”.

By 1978, the New York Times went so far as to say that Shell was “busier in Venezuela than before the oil industry was nationalized”.

Venezuela: The Fable of ‘Political Prisoners’ and Complicit Silence in the Face of Kidnapping

‘Shell has been active‘

Even still, Britain’s oil firms wished to return to Venezuela’s oilfields.

Those hopes were stoked in the early 1990s by the “Oil Opening” of President Carlos Andrés Péres, whose austerity measures led to an explosion of poverty and street protests, but dashed once again by Chávez’ proposed Hydrocarbons Law in 2001.

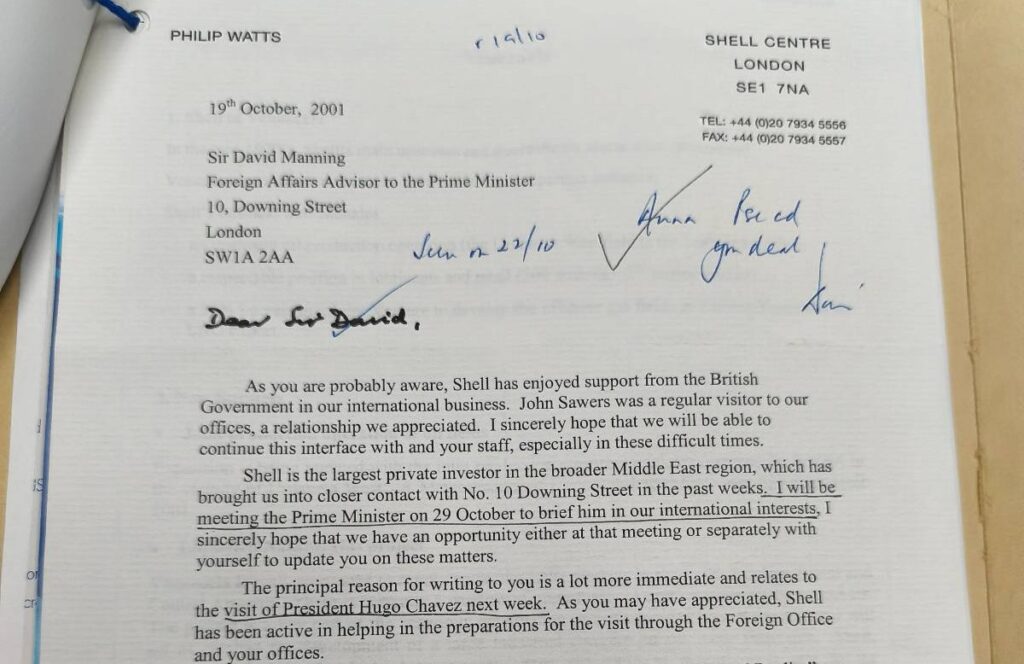

In the lead-up to Chávez’ visit that year to London, Britain’s leading oil companies were once again in the prime minister’s ear about the projected impact on their interests.

Blair’s briefing noted unambiguously that UK and US companies were “concerned” about the oil reforms and wanted them watered down.

Days before the visit, Shell’s chairman Philip Watts offered suggestions on how Blair might handle Chávez.

“As you may have appreciated, Shell has been active in helping in the preparations for the visit through the Foreign Office”, Watts wrote.

“Considering the importance of the energy sector for both the Venezuelan and UK economies, I thought the PM may appreciate a small briefing on our… plans in Venezuela”, he added.

Those plans involved ameliorating the “uncertain investment climate” and softening the “fiscal and legal framework” in the country.

As part of the charm offensive, Watts also hosted a “farewell” banquet for Chávez, to which foreign secretary Jack Straw and other senior ministers were invited.

BP and BG Group also “registered their interest with No.10 about the visit”, with BP preparing “to put their case… forcefully” in favour of a meeting between the two leaders.

‘The Americans are concerned‘

The US government also weighed in on the matter.

On 18 October, an official in the British embassy in Washington wrote to London that “the Americans are concerned about the impact that the Hydrocarbons Law will have on investment in the energy sector”.

They continued: “The major oil companies, including BP, had all made clear that its tax and restrictive joint venture productions would hinder their operations”.

The US state department “thought it would be particularly useful for Chavez to hear these concerns in London, given his tendency to discount messages from the US”.

To this end, the George Bush administration hoped Blair would “talk sense into [Chávez] on the Hydrocarbons Law, where BP are among those who stand to lose”.

Further pressure was applied by Gustavo Cisneros, a Venezuelan billionaire and media mogul who was introduced to Blair in 2000 by Daily Telegraph owner Conrad Black.

Sawers, Blair’s adviser, noted that Cisneros’ “sole message” for Blair “was that Chávez was a real danger to stability and free markets (and, of course, rich Venezuelans like himself)”.

A briefing document prepared by Cisneros, for instance, warned that “Chavez will likely react” to oil prices dropping “by lashing out at the private sector”.

Sawers viewed Cisneros with suspicion but broadly agreed that Chávez was objectionable. There was, he wrote, “a chance that the picture [with Chávez] at the front door [of Downing Street] would come back to haunt us”.

He continued: “This is one of the World’s tyrants whose hand I won’t have to shake”.

The coup against Chávez

A coup against Chávez broke out in April 2002, orchestrated by dissident military and political figures with support from Washington.

Pedro Carmona, an economist who was unconstitutionally appointed Venezuela’s president, quickly set about dismantling the country’s democracy and reversing Chávez’s oil reforms.

He happened to be in the offices of Cisneros, the mega mogul who had taken the opportunity to “pour poison” into Blair’s ears about Chávez, when the coup broke out.

The declassified files show how Britain quietly hoped the Carmona regime would be more accommodating to foreign interests while noting the unconstitutional nature of the coup.

“The Cabinet is strong on experience and business” and “hopefully its management capability will be much higher”, wrote the British embassy in Caracas.

The embassy was also informed by UK business leaders in Venezuela that “their operations should be back to normal by 15 April”, while Shell’s “production of oil was unaffected”.

At the same time, however, the Foreign Office was disturbed by the fact that “no one” had “ever elected” the Carmona regime.

“Venezuela may or may not have wanted to get rid of Chavez, but not necessarily to lose the other parts of their democratic system”, one official wrote. “The right-wing businessmen seem to have shot themselves in the foot”.

Notably, the UK government seemed to have some knowledge of Washington’s role in the events.

On 14 April, with Chávez imprisoned in a military barracks, the British embassy in Caracas cabled to London that the US ambassador had been spending “some hours in the Presidential Palace”.

“Please protect [the information]”, they instructed.

The opposition

The coup was short-lived.

Chávez was reinstated within 47 hours following a wave of popular mobilisations across Caracas.

With Chávez back at the helm, the Foreign Office quietly hoped that “the events of the last few days” would be seen as “a serious warning to change his ways”.

But the situation remained tense, with UK foreign secretary Jack Straw noting in July 2002 that Chávez’s position “remain[ed] shaky”.

The political opposition in Venezuela was seen by Whitehall as particularly intransigent, with Straw declaring that Chávez looks “positively resplendent compared with [them]”.

The Venezuelan opposition, Straw continued, “appear to be united, indeed motivated, by sheer indignation that someone like Chávez (not one of them and above all not white) should be in charge and have such a popular power base”.

An official in Britain’s embassy in Caracas similarly noted in 2002 that the Venezuela opposition “looks like a train that tried to breach a wall on one track in April and are now seeking to do the same on a slightly different track and at a slightly different angle”.

They added: “The opposition’s self-delusion is growing worse by the day: they claim alternately they are living in either a fascist or communist dictatorship”.

One of the key opposition figures in this period was María Corina Machado, with whom the UK government is currently in talks amid a renewed regime change campaign in Venezuela.

Independent journalist @theCanaryUK, @jacobinmag, @ColombiaReports , & International History Review.