By Henriette Chacar – Sep 3, 2021

Recording under quarantine, a musical trio gives a classic blues song an Arabic twist, exploring new depths for Black-Palestinian solidarity.

As you read, listen to our curated Spotify playlist inspired by this story.

For Kareem Samara, a British-Palestinian multi-instrumentalist, composer, and sound artist, it was naseeb — meant to be. One day in 2020, American-Palestinian filmmaker and music producer Sama’an Ashrawi messaged asking him to play “Baby, Please Don’t Go,” an American blues standard, on the oud. Ashrawi was curious what the blues would sound like in the quarter tones of the Middle Eastern instrument. Minutes later, Samara sent him a recording of the tune.

“It’s a song I’ve always loved,” says Samara. “That song is in my bones.”

Ashrawi and Samara met in 2019 in Palestine, when Samara was on a visit to trace his Palestinian history. His mother’s family had fled Jaffa to Egypt during the Nakba, and he was the first of his relatives to return to Palestine since 1948. At the time, Ashrawi was researching Al Bara’em, considered Palestine’s first original Arabic rock ‘n’ roll band, which his father had started with his siblings in the 1960s.

“Baby, Please Don’t Go” is likely an adaptation of a folk song from the time of slavery in the United States. Most variations of the theme can be traced back to the 1935 version recorded by Delta blues artist Big Joe Williams, whose lyrics relay the fear of a lover leaving “back to New Orleans.” One of the lines in the original version — “I believe that the man done gone, to the county farm, Now with a long chain on” — suggests the singer is a prisoner begging his lover not to move away before he is released.

The song has since been covered by several blues heavyweights and rock bands, including Them, AC/DC, and the Rolling Stones. For Ashrawi, however, the version that has stayed with him is that of famed country blues singer and guitar innovator Samuel John “Lightnin’” Hopkins. “The guitar riff on that song is so memorable, it will always be in my head,” he says.

Samara suggested they turn the oud recording into a track. “He was, like, ‘Do you know anyone who could sing on this?’ And the first person I thought of was my friend Kam Franklin,” Ashrawi recalls. Franklin, a songwriter and the lead singer of Texas soul group The Suffers, accepted the invitation.

“To me, it felt really special to have Kam on the song, and I wanted to make sure there was some element aside from just her voice that made this version Kam’s thing,” says Ashrawi. That’s when he thought of replacing “New Orleans” in the original lyrics with “Third Ward,” the Houston, Texas neighborhood where Franklin is based, and where Lightnin’ Hopkins lived.

It is also where George Floyd, a Black man whose murder at the hands of a police officer in Minneapolis last year sparked a global wave of reckoning, grew up and mentored young men. “Black Americans have shown solidarity with Palestine, and we show solidarity back, but maybe not enough,” says Samara. “This is a great way of showing solidarity in a way that maybe hasn’t been done before.”

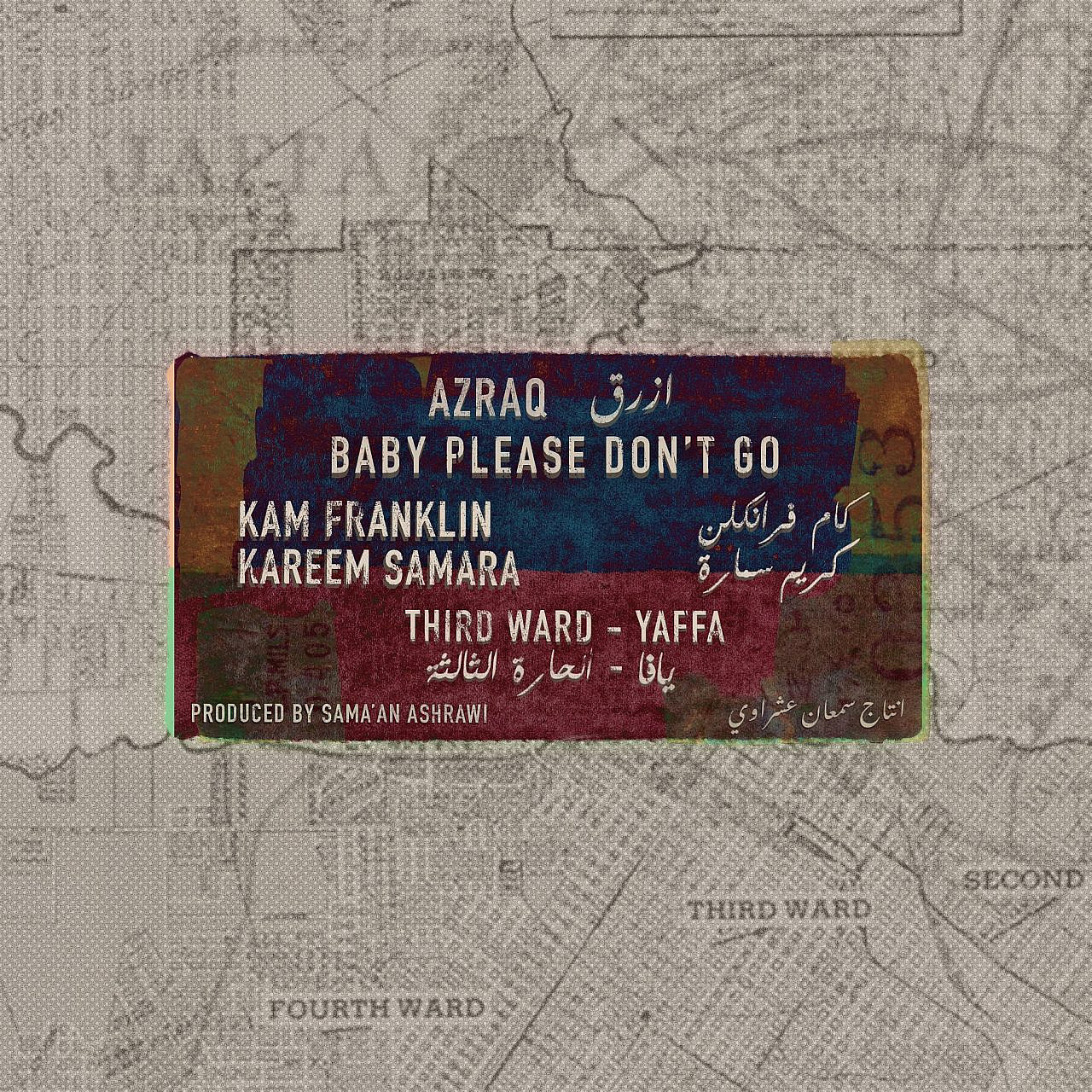

What started as an accidental one-off collaboration turned into a new band called Azraq, meaning “blue” in Arabic, featuring Ashrawi, Franklin, and Samara. Despite COVID-19 delays, the trio is working on new music, experimenting with original demos and blues versions of traditional Palestinian songs.

“Thinking about the severity of the oppression that Black people have gone through in the United States, and thinking about the pain and oppression that Palestinians have gone through — in both cases, it’s a pain that comes from colonialism,” reflects Ashrawi. “How can we bring the sounds of Palestine with the sound of blues, and also the feelings of both? That’s the intersection we’re exploring.”

In search of authenticity

When playing in a band, the best performance comes from eye contact and from feeling, says Samara. But with the three quarantining in different cities following the coronavirus outbreak, WhatsApp became their way of staying connected while working on the track. The music and vocals had to be recorded separately, “and we weren’t using a click,” explains Samara, referring to a digital metronome that helps musicians stay in sync. “There’s gaps, there’s thoughts going on in the recording, there is a delay sometimes before one of the bars come in, there’s points where we cross over. There’s points where she [Franklin] does something in her voice that is so perfect that if I was to edit it, it would take away from even the imperfection of me playing with her incorrectly.”

Deciding to produce the track this way, while more challenging, gave it more of a “live” feeling that allowed the trio to stay true to the unrefined, improvisational nature of blues music. “I’ve always looked for honesty. I’ve always looked for rawness. I’ve always looked for some kind of authenticity in the sound,” says Samara. And blues not only allows musicians to get away with this authenticity, it is a defining feature of the genre. “With blues, there is a structure, there is an idea, there is a scale, but when that person got on their guitar, they could do anything they wanted.”

Samara’s home studio, where he recorded the music for the track, is set up precisely to facilitate this organic sound. The medium-sized room isn’t soundproofed and gives off a slight reverb, which isn’t considered optimal when recording music.

Samara’s “very indie, very lo-fi” production process usually involves a laptop, keyboard, drums, oud, and guitar. For this cover, in addition to the oud and Franklin’s singing, Samara added a bass guitar; riq, a traditional tambourine common in Arabic music; Arabic and Kurdish darbukas, hourglass-shaped hand drums that he held in his lap simultaneously; and Syrian bells that go over the feet, which a friend had bought him from Jerusalem. “It looks very fancy and complicated, but it’s not.”

The song opens with a drone sound that Samara created using his keyboard. “I’m a big fan of patience, and atmosphere, and setting the scene,” he says. The drone “was the right thing to give it some space.”

While discussing how best to integrate the drone and the percussion, Franklin said she had an idea. “Within a day, she sent back the ‘oohs’ that you hear at the end,” says Samara. “It makes that ending so much more haunting and special.”

‘The guitar doesn’t sound like the oud’

Ashrawi, whose father is Palestinian, grew up in Cypress, Texas, a town about 24 miles northwest of Houston. Though he recalls having few Arab neighbors, there were markers of Arab identity all over his family home: his grandmother’s tatreez, Palestinian embroidery tapestries, adorned the walls; his father would listen to Fairuz and the Rahbani Brothers; even the pajamas he remembers wearing as a child had Arabic writing on them.

Framing Ashrawi in the Zoom interview was a grid of record covers hanging on the wall, from Gil Scott-Heron, to the Commodores, to Ray Charles. “That gives you a good idea of what I grew up with,” he says. “A lot of Beatles, a lot of Led Zeppelin. A lot of jazz — so much jazz.”

Growing up, Ashrawi played the piano and the saxophone. Sometimes, he flirts with the idea of learning to play the guitar, but “to learn guitar, you have to build calluses on your fingers, and I like having soft hands,” he says.

In high school, Ashrawi saved a summer’s worth of lifeguarding money to install big speakers in his car trunk. “I still have friends who will remember me by certain songs I played in the high school parking lot,” he says, listing Three 6 Mafia’s “Poppin’ My Collar” and UGK’s “Cocaine” as examples. In college, he took on deejaying and would use GarageBand, a digital music production software, to create beats on his laptop. “I had ideas for what I wanted to hear, but I just didn’t have the drive to physically make those beats myself,” he says. This is when he decided to get involved in music production: “It gave me the idea that this was something I would be interested in, but that I didn’t necessarily need to be the one pressing all the buttons.”

Samara’s experience with music, on the other hand, is a lot more hands-on. He grew up playing the guitar at school, and was a member of several rock bands. Later, he worked in music publishing, placing music in films, and teaching guitar.

RELATED CONTENT: Palestine’s Africa Dichotomy: Is Israel Really ‘Winning’ Africa?

“My mother would complain that the guitar doesn’t sound like the oud. If I was playing Um Kulthoum, or something that I heard on her tapes,” he says, referring to the Egyptian musical icon, “I could never really get the quarter note, or even the full scales of some of the stuff that they were playing.” On one of his trips to Egypt, he bought an oud, but it would take him years to finally muster the confidence to play it.

Defying despair

The blues is a musical genre created in the Deep South by African Americans. Blues songs are usually stories of suffering and loss, a cry that is also meant to assuage the pain. But blues “has a more profound, spiritual side: defying despair,” Dr. Sylviane Diouf, a historian of the African diaspora and visiting scholar at the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice at Brown University, writes in a recent essay.

The musical genre was heavily influenced by Muslim traditions, which were brought to the United States with the enslavement of hundreds of thousands of Muslim West Africans starting in the early 1500s. Relatively little is known about these communities and their contributions to American culture, though, partly because the history of enslaved Africans has largely been ignored, and not always willfully — many historians simply didn’t have an understanding of African and Islamic cultures, and therefore didn’t recognize their existence or influence in the archives, Diouf explains in a phone interview.

“I’ve read hundreds of books about slavery and the slave trade. My dissertation, when I was in college, was about resistance and revolt in the Americas. And I was surprised that I couldn’t find mentions of the Muslims,” says Diouf. This led her to ask: given that there were Muslims in Senegal, Mali, and Guinea, among other places, why don’t we find them in the books that have been written about slavery?

Taking matters into her own hands, Diouf began investigating sources in French, English, Spanish, and Portuguese, uncovering a rich yet overlooked history. “When you look for something, you find it,” she says. Her discoveries were first published in a 1998 book titled “Servants of Allah.” A second edition was published in 2013.

From her research, Diouf learned that the stories of enslaved Muslims have also disappeared because of the way the trans-Atlantic slave trade separated African families. Since it was mostly men who were sold and deported, they either didn’t have children or eventually married non-Muslim women. Even in countries like Brazil, which had big, strong Muslim communities of Africans who had been enslaved and freed, passing on the faith to the children became difficult: younger generations saw Islam as an “austere” religion that would position them as a minority, and “it was more ‘fun,’ to use modern terminology, to be a Christian,” notes Diouf.

But there are reasons why the blues took root only in the United States, and not in the other colonies. There, enslaved West Africans recreated stringed instruments that they had been playing for thousands of years, like the banjo, different kinds of lutes, and the fiddle, which eventually evolved into the guitar. And when non-Muslims heard the adhan (call to prayer), Sufi chants, duas(supplications) or lamentations, they would have perceived them as another type of African music, which they then imitated and spread. Decades later, these practices, fused with other African music traditions, evolved into the shouts and hollers that led to the blues.

“It was most likely these audible expressions of Muslim faith, and not merely what the musicians brought over, that generated the distinctive African American music of the South,” Diouf writes in her essay. One striking example that she highlights is “Levee Camp Holler,” a tune that formerly enslaved African Americans sang while building the Mississippi Valley levees in post-Civil War America. “It is almost an exact match to the call to prayer by a West African muezzin,” writes Diouf. “When both pieces are juxtaposed, it is hard to distinguish when the call to prayer ends and the holler starts.” (Interestingly, the first muezzin was a formerly enslaved man from East Africa appointed by the Prophet Mohammad.)

This style of singing, featuring nasal, wavy intonations and melisma, the expression of many notes over one syllable, is still popular throughout the Muslim world. In Azraq’s rendition of “Baby, Please Don’t Go,” it can be heard in the reverberations of the oud, and the quivers and shakes in Franklin’s vocals.

Henriette Chacar (she/her) is the deputy editor and a reporter at +972 Magazine, who also produces the magazine’s podcast. She previously worked at a weekly paper in Maine, The Intercept, and Rain Media for PBS Frontline. Henriette graduated from Columbia University with a master’s in journalism and international affairs.

Featured image: Untitled, from the series ‘Islam Played the Blues’ by Toufic Beyhum. (www.tbeyhumphotos.com)

Tags: Colonialism Slavery