By Chesa Boudin – Mar 8, 2021

For Chesa Boudin, his mother and father were radical not for their politics but for the extraordinary lengths they took to parent him while incarcerated.

Toward the end of a weekend trailer visit to my incarcerated father in New York State in 1992, when I was 12, I had an emotional meltdown—and not for the first time. Trailer visits are occasional overnight accommodations provided to family members of people serving long sentences who’ve kept a good disciplinary record. On that particular weekend, I’d brought a stack of homework that I had to complete before school on Monday. We’d had a couple of happy days together, cooking epic meals of fresh vegetables, tofu, and brown rice, playing chess and cards, watching movies—even as I refused his advice to do my homework the whole time. (Sound familiar?) On the second and last night, I had a temper tantrum: I didn’t want to do my homework, or at least that was the trigger for a lot of pent-up emotion. The joy of every prison visit was punctured by the grim realization that I was going to have to leave, and that my dad would not be coming with me. In a fit, I threw all my homework out the window into the dark, windy yard. In that otherwise banal act of rebellion, I created a terrible dilemma for my father. He could leave the trailer to chase down my papers in the dark before they blew away, violating a prison rule and risking a discipline violation, or “ticket,” which would not only tarnish his perfect record but also forfeit future visits with me. Or he could protect himself and our access to the trailer visits by doing nothing, sending me home the next day without my schoolwork. He put me first.

When I was 14 months old, my parents, David Gilbert and Kathy Boudin, dropped me off with a babysitter. They never came back. That day, while I was playing, my parents drove a van used as a switch car in a bungled armed robbery. Though neither of my parents was armed or intended for anyone to get hurt, two police officers and a security guard were killed. My parents were arrested and charged with felony murder—an anachronistic legal doctrine that allows prosecutors to punish almost any participant in a serious crime resulting in death, no matter their role, with murder. In one of the countless capricious outcomes of the criminal justice system, my mother ended up serving 22 years while my father received a minimum 75-year sentence. Though they played nearly identical roles in the crime itself, my father refused legal representation and went to trial, ultimately getting convicted of all the charges and receiving the maximum possible sentence. By contrast, my mother had excellent lawyers and, on the eve of her trial, pleaded guilty for a negotiated sentence. After 39 years, my father remains incarcerated. Absent a change in law or a grant of clemency from New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, he will not be eligible for parole until he is 112 years old.

I don’t remember that tragic day, of course—getting picked up by my grandparents or, weeks later, being taken into a new family that already had two young children, who were now my older brothers and would become, in time, my loving defenders and greatest supporters. But I do remember, from my earliest days, waiting in lines to get through metal detectors, steel gates, and pat searches just to see my parents, just to give them a hug. I did not understand that my parents’ crime had been organized by the Black Liberation Army, and that they were in it not for money but because of a misguided vision of radical racial solidarity. Yet, even as a small child, I noticed that the lines at the prison gates were mostly made up of Black and brown women and children. Those kids and I had all paid a price for our parents’ mistakes, and for our country’s retributive obsession with prisons.

My parents’ arrest in New York in 1981 came just as the addiction to incarceration was ramping up. Today, the United States leads the world in locking people up: With less than 5 percent of the world’s population, we have approximately 25 percent of the world’s prisoners—2.3 million people behind bars on any given day. What’s more, the majority of people in prisons are parents, and there are far more children with an incarcerated parent than there are prisoners. Because of the constant churn of people in and out of incarceration, one in 12 American children will experience parental incarceration.

RELATED CONTENT: Mumia Abu-Jamal, Now in his 40th Year as an Incarcerated Prisoner, has Covid-19

Parents and children fighting to overcome the distance created by incarceration must be determined, courageous, creative, and more. My father and mother were relentless in their effort to develop into the parents I needed, even as they negotiated the complex landscape of incarceration. Shortly after their arrest, while still in county jail awaiting trial, they were denied any contact visits. Not willing to accept a relationship with their toddler son through plexiglass, my parents filed a lawsuit in federal court. To be sure, most incarcerated families confront demoralizing obstacles like denial of visits or limits on phone calls, and far too few have the resources or social capital to effectively push back. We were luckier than most. In ordering the warden to allow us contact visits, a federal judge wrote, “The importance of contact visits to the detainees, their family and to the institution cannot be understated,” and cited a renowned psychiatrist in explaining that “contact visits not only restore decency and humanity to the penal system, but also perform the critical function of reestablishing the prisoner’s connection with the world existing outside the prison walls.”

Over subsequent decades of prison visits, I learned that not all contact visits are created equal. After sentencing, my mother spent the rest of her sentence in New York State’s only maximum-security prison for women: Bedford Hills Correctional Facility. Thanks in large part to a saintly Roman Catholic nun, the late Sister Elaine Roulet, Bedford Hills was a model of what a family-centered approach to visitation should look like, even if it happened inside miles of razor wire and steel gates. Bedford Hills is located just 40 miles from New York City and is accessible via public transportation. Geography matters, because while more than 60 percent of inmates in New York State prisons come from the New York City metropolitan area, most of the state prisons are located much farther away. Cuomo recently signed into law long-overdue legislation that will direct the state’s Department of Corrections to place incarcerated parents in facilities closer to their minor children; the law is a critical part of recognizing the multifaceted identities of the people we incarcerate, most of whom are parents.

Sister Elaine established a parenting center at Bedford Hills that helps mothers arrange visits and maintain contact with their children. The prison has a large visiting room, part of which is dedicated to the Children’s Center, designated exclusively for mothers and children. I have fond memories there of making piñatas, building with blocks, painting at easels, playing with a teddy bear my mom had sewn for me, and listening to her read The Count of Monte Cristo to me. Sister Elaine also spearheaded a summer program in which children from New York City visit every day for a week and engage in a range of group activities. During one precious week each summer, my mom and I played volleyball and had water fights on the visiting-room patio.

These visiting opportunities are not available in most prisons, and many states have nothing comparable. Far more common is what I experienced each time I made a normal day visit to one of my father’s prisons: wall-to-wall tables with incarcerated people on one side and visitors on the other. No privacy. No carpets. No outdoor space. Limited contact, allowed only at the beginning and end of the visit. No space to move around or do much of anything other than sit there and talk until a correctional officer announces visiting hours are over. Until 2020, at least one state, New Hampshire, prohibited toys in the visiting room. Until 2013, Utah prohibited any language other than English from being spoken on visits. As my friend Emani Davis, who grew up visiting her father in Virginia prisons, put it, “We’re told prison visiting rooms are set up for security and control; to kids, they feel designed to kill the human spirit and deter us from coming back.”

My father has now served nearly 40 years, divided unevenly among six different prisons in upstate New York. Luckily for us, however, New York is one of just a handful of states that offer overnight visitation. For 48 hours, twice a year or so, I’ve gotten a taste of living with my dad—albeit under the shadow of razor wire, punctuated by regular prison counts. The two-bedroom trailer homes inside the prisons have a mostly functioning kitchen and, during daylight hours only, access to a tiny fenced-in yard. I usually made the long trip to upstate New York by flying on my own, and then a family friend or a local volunteer would take me grocery shopping and drop me off at the prison gates. It was these visits, more than anything else, that gave David a chance to be a father—my father.

Beyond homework and home-cooked meals, the trailer visits were a space for difficult conversations. Sure, we talked about the things sons talk about with their fathers, but more than that, we talked on every visit about how and why he was fathering from prison. There is no right way to tell your son that you participated in an armed robbery that resulted in three murders. My father consistently expressed deep remorse, took responsibility, and met me where I was emotionally—whether angry or sad or confused. In explaining the irreparable harm the crime caused, he told me that the men who were murdered had wives and children; some of those children were around the same age as I was and would never know their fathers because of the crime he’d participated in. Even though, as a child, I fixated on my father’s limited role as an unarmed driver, I never made it easy for him. I insisted that he repeatedly tell me what happened and what he did. I wasn’t interested in gore—my dad wasn’t even present at the robbery—but I had questions: Why would you do something so dangerous? Didn’t you worry that people might get hurt? And one question no words could ever answer: Why would you risk losing me?

RELATED CONTENT: Finding Meaning Under a Meaningless System

Given how rare and expensive prison visits tend to be, what happens between those visits is critical. For my entire life, my parents have called me at least once a week—a luxury most families can’t afford, no matter how determined the incarcerated parent is to maintain contact. As a child, I’d sometimes get off the phone and cry to myself, “If only I could have talked on the day of the robbery, I’d have told them not to go.” But mostly, my parents managed to make the calls fun. For several years straight, my dad would tell me adventure stories. Each call was a new chapter in an ongoing saga starring me and my friends on escapades around the world and beyond. I relished the story time, and in those recorded collect calls, my dad found small ways to act out his love.

Though he couldn’t always get access to the phone, my dad sent me letters nearly every day. Sometimes it would be nothing more than a piece of colored construction paper with a big heart on one side. Other letters included photos meticulously torn out of National Geographic. Even before I could read, those letters were a critical part of maintaining and building a bond beyond the bars. Writing letters is an often unattainable luxury for many incarcerated parents because of both the cost of postage and widespread literacy challenges: 40 percent of the people in prison never completed high school. Each stamp my father bought in the commissary cost more than an hour’s worth of wages from his prison jobs—mopping floors and facilitating anti-violence trainings for other inmates—but he kept writing his love and regrets a million different ways.

Today, my father is 76 years old. He is one of the oldest and longest-serving people incarcerated in New York State’s prisons. He is likely the only person who has been in that long without a single disciplinary violation on his record—even though he found a way to make sure I completed my homework on time. At my age, and his, I’m supposed to be taking care of him. Instead, in the midst of the pandemic, I have not been able to visit once in over a year, even as more than 100 people in his prison have tested positive for Covid-19. Yet every Saturday afternoon, when he calls, instead of complaining, he does what he has always done for me since that tragic day in 1981: parent. Even while confined to a cage, year after year, decade after decade, he has parented through letters and calls and help with homework. Most of all, my dad, David Gilbert—inmate number 83A6158—has parented by living a life grounded in principle, in accountability, and in love.

Prisons and jails do not promote parenting; they seriously impede it. When a parent commits a crime, the system largely overlooks their parental obligations—and the rights of the children left behind—in favor of punishment. Virtually every jurisdiction in the country requires sentencing judges to consider victim impact statements, but children of defendants are not considered victims, so the impact on them is systematically ignored. So-called family values are jettisoned in favor of draconian responses to all manner of crimes. While some prisons have marginally more child-friendly policies, none of that could ever make prisons appropriate places for parenting. Indeed, the reductionist labels of “felon” or “inmate” or “83A6158” can easily dwarf the nuanced identities of “mommy” or “daddy.”

After more than two decades of mothering from prison, my mom was released in 2003. More than 17 years later, my father is still living in a cage. Some call my parents radicals because of things they did before I was born or because of their involvement in the tragic armed robbery when I was a baby. In my lifetime, in my experience, the most radical thing about my mom or my dad is their unwavering dedication to being loving parents.

Chesa Boudin is the district attorney of the City and County of San Francisco.

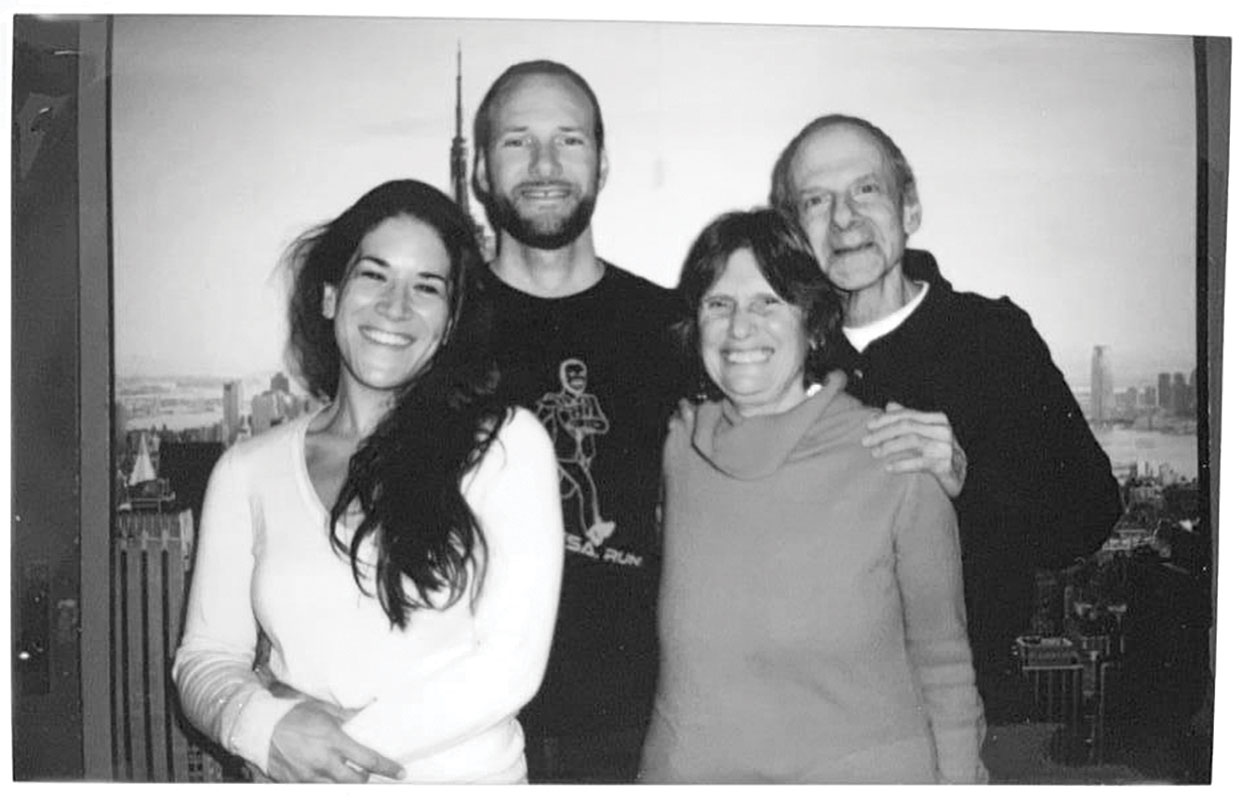

Featured image: Reunited, for a moment: The author with his parents circa 1982, in a jail visiting room after the family was allowed contact visits.

Tags: Chesa Boudin US decline