BP directors meet in London, 1960. Photo: Central Press / Getty.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

BP directors meet in London, 1960. Photo: Central Press / Getty.

By John Mcevoy – Aug 31, 2022

Formerly top secret files show how the two oil corporations bankrolled UK covert propaganda operations during the 1950s and 60s. The goal was to secure British access to key oil supplies across the developing world.

“Handsome” sums were provided by BP and Shell to the Information Research Department (IRD), which was Britain’s Cold War propaganda arm between 1948 and 1977, declassified files show.

The IRD used the secret subsidies to fund British covert propaganda operations during the 1950s and 1960s across the Middle East and Africa, where Britain’s oil interests were substantial. Today, the value of the payments would be in the millions of pounds.

Such operations involved setting up newspapers and magazines, funding radio and television broadcasts, and organising trade union exchanges.

The objective was to promote “stability” in these regions by countering the threat of communism and resource nationalism, while improving the “public image” of Britain’s leading oil companies.

Ultimately, the goal was to secure British access to the supply of Middle Eastern and African oil.

Oil and propaganda

During the 1950s and 1960s, the IRD met annually with Shell and BP representatives to discuss how secret oil subsidies were being used and whether the oil companies were getting value for money.

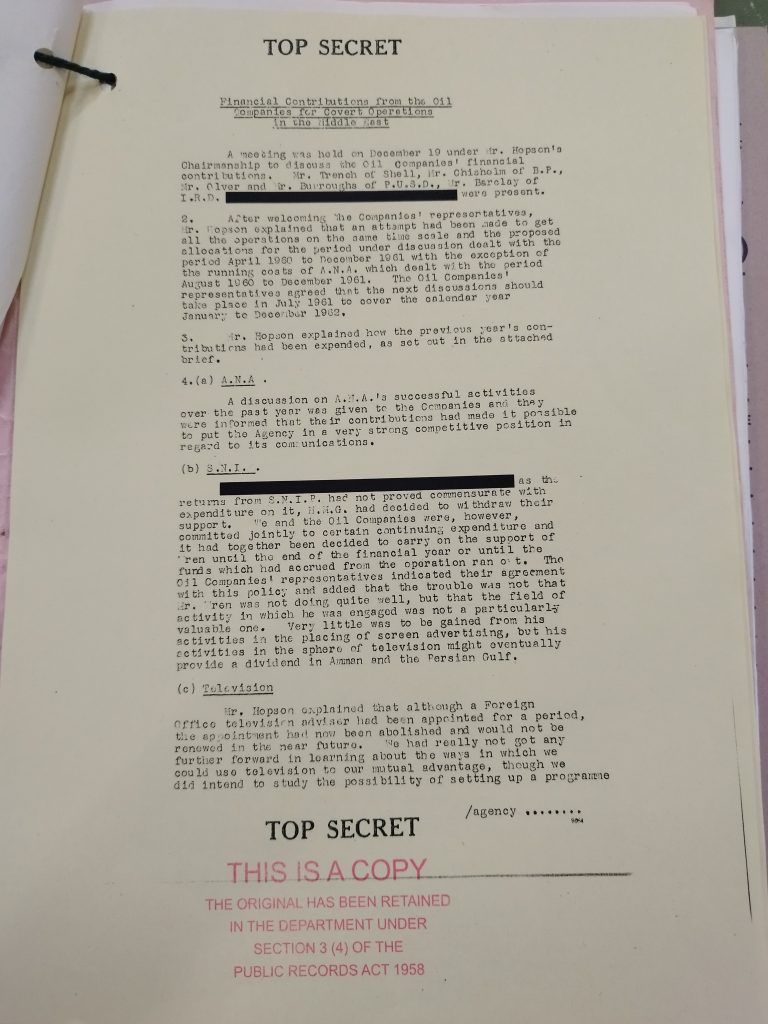

In December 1960, IRD chief Donald Hopson met Shell’s UK executive Brian Trench and senior BP executive Archie Chisholm, alongside a number of other Foreign Office officials. The name of one individual remains classified, suggesting Britain’s intelligence services were also in attendance.

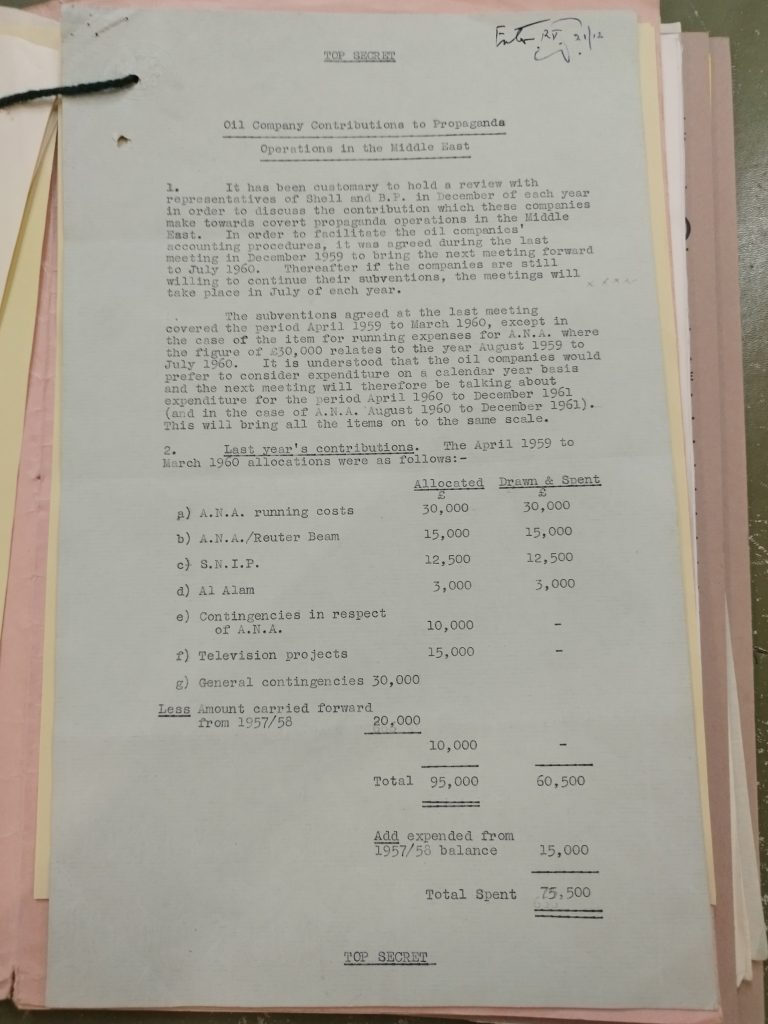

At the meeting, it was noted the IRD had spent £75,500 in oil money – valued at over £1.2m today – on covert propaganda operations between April 1959 and March 1960.

Over half of this money had been spent on the Arab News Agency (ANA), a long standing British propaganda front which had strong links with MI6.

“ANA operated the most comprehensive service in English and Arabic available in the Middle East with branch offices in Damascus, Beirut, Baghdad, Jerusalem and Amman, and representatives in some 15 other cities, including Paris and New York”, wrote journalist Richard Fletcher.

Hopson informed the oil companies “that their contributions had made it possible to put the [Arab News] Agency in a very strong competitive position in regard to its communications”.

For instance, oil company subsidies allowed ANA to pay for British news agency Reuters’ wire service. During this period, Reuters was pliable to UK government influence, and was seen as a useful propaganda instrument.

With this, ANA could supply news organisations across the Middle East with Reuters’ content. The service was described as “very successful in Egypt”, and it “secured the first place for Reuters in competition with the other world agencies”.

It is unclear whether Reuters was aware that the UK government was secretly channelling oil money into its accounts. One UK file, dated 1960 and entitled “Information Research Department: renegotiation of contract between Reuters and the Arab News Agency”, remains classified by the Foreign Office.

‘Valuable propaganda instrument’

On top of this, the IRD used £3,000 of oil money to fund Al Aalam (“The Globe”), an ostensibly independent magazine published in Iraq, which was seen by the Foreign Office as “a most valuable propaganda instrument”.

Al Aalam supported UK anti-communist efforts and sought to counter anti-British messaging coming from Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt. At this time, Nasserite Arab nationalism posed a significant threat to Britain’s regional interests, and was a central focus of British propaganda activities.

The IRD thanked Shell and BP for their “handsome contributions”.

The oil companies’ contributions to Al Aalam, which had been ongoing since the early 1950s, “had in fact tipped the scale when the Treasury decision concerning the launching of the periodical was made”, it was noted. In 1960, the magazine achieved a monthly circulation of 85,000.

During this period, £15,000 in money from the oil companies was also “expended in Iran” on “emergency operations” which enabled “visits to be arranged, publication and translation work to be undertaken, and training schemes for Persian radio officials to be put in hand”.

‘Handsome contributions’

The IRD thanked Shell and BP for their “handsome contributions”, and requested an additional £138,750 in secret funding for the period April 1960 to December 1961. Indeed, these were “handsome contributions”, amounting to roughly 8 percent of the IRD’s annual official budget, and valued at £2.25m today.

“The general pattern of ANA’s activities would continue to be the same though the Agency would concentrate in the forthcoming year on strengthening its news collecting”, an IRD memo noted. To this end, the IRD requested an additional £42,500 for ANA’s running costs, and £26,250 for Reuters’ wire service.

On top of its pre-existing operations, the IRD proposed using oil subsidies to fund a number of new ventures.

One such project was geared towards building up “sufficient influence with certain selected Libyan Trade Unionists” in order to “encourage a spirit of moderation into industrial demands”. This issue was seen as “of direct interest to the oil companies” such that the IRD could “anticipate their support”.

‘Student news service’

In Latin America, the IRD wished to “interest ourselves particularly in the student and trade union fields” by setting up a “student news service” with oil company contributions.

On top of this, the IRD requested £5,000 for a “trade union exchange visits scheme”. The scheme had already begun in Latin America, and the IRD was looking for oil money to expand the project into Africa.

It was also “hoped to start an examination of the possibilities of setting up a [television] programme agency for the Middle East shortly”.

The agency’s core objective was “the preservation of [British] oil interests in the Gulf”.

Another project focused on news agency Gulf Times/Al Khalij, an IRD outfit based in Beirut, which was looking to expand and open a new office in Kuwait.

According to one IRD document, the agency’s core objective was “the preservation of [British] oil interests in the Gulf”. It was noted that the oil companies may thus “think it suitable to contribute [£30,000] towards the capital cost of the new venture”, which was valued at £110,000. This project, however, was ultimately abandoned by the IRD in April 1961.

‘Handmaid of BBC Arabic’

In 1963, the oil companies funded Huna London (“This is London”), a magazine which was described by one IRD official as “the handmaid of the BBC Arabic service” and “the best means we have of addressing the Arabs as a whole”.

Huna London had been the words used to announce the first BBC broadcast in Arabic in 1938, and the magazine would become the Arabic equivalent to the Radio Times, which listed British television and radio programmes alongside “contributions from leading writers and illustrators of the day”.

Oil money had “enabled 6,000 extra copies” of Huna London to be printed in 1963, “each requested by an individual Arab, to be sent out from Beirut”. The IRD envisaged that it might soon receive “requests for 100,000 or more copies”, which was described as a “highly desirable” outcome.

One proposed project remains redacted in entirety.

‘Contingency money’

Beyond this, the oil companies provided the IRD with tens of thousands of pounds in “contingency money”, which was to be used as “a stimulator of desirable projects”.

Norman Reddaway, a seasoned British propagandist based in the British embassy in Beirut, described the contingency fund as “particularly useful for pump-priming and for persuading people that desirable things could be done in advance of agreement by London”.

The oil companies felt the IRD was making good use of their money and, by 1960, they wanted to help British propaganda operations expand.

For instance, Shell was “widening their field of interest and… thinking in terms of propaganda in distribution areas as well as in producing territories. They are thus concerned with the public image of the oil companies in places like West Africa as well as in the Middle East”.

As a result, the IRD “could take it that” the oil companies “had an interest in all production and refining areas and territories adjacent thereto. Thus, for example, Somalia was an area of interest because of its proximity to Aden”.

Pump-priming

By late 1963, Shell and BP were beginning to express irritation at the IRD’s continued reliance on oil funds for ongoing projects.

Shell and BP had intended to pump-prime British covert propaganda projects so that these ventures could become self-sustaining. The oil companies, it was noted, were happy to help propaganda projects get off the ground but “did not like involving themselves in continuing commitments”.

In private correspondence dated 16 December 1963, Chisholm told Foreign Office official Leslie Glass that: “the object originally of the exercise on which we are engaged was to assist you to overcome certain financial restrictions in getting things moving at a critical and difficult time. We have been glad to continue our assistance with certain of these projects to our mutual advantage”.

Chisholm continued: “It was always our intention, however, that as projects reached full development and they justified financing from other sources, our contributions to them should tail off”.

“Secret oil subsidies, in other words, were seen as central to the success of Britain’s propaganda operations in the region.”

Shell Shocked in Amhara, Ethiopia: “I don’t Even Want to Hear the Word ‘America’ ”

Trench agreed, expressing hope that ANA, the Reuters service, and the Ariel Foundation – a British front organisation which facilitated exchanges of trade unionists and academics – “could be entirely financed from other sources by about 1966”.

The oil companies also found covert payments an awkward affair. Chisholm, for instance, “asked whether a less complicated method of making subventions was desirable”.

The IRD was not satisfied. In a draft response to Trench, one IRD official noted that “we are… faced always with the preliminary difficulty of being able to only approach you regarding projects which have a territorial interest common to you and your friends”.

Moreover, the IRD emphasised that “the result of a cessation of your [oil company] support would be that… undertakings would have to be cut down and be less freely available in the areas of common interest”.

Secret oil subsidies, in other words, were seen as central to the success of Britain’s propaganda operations in the region.

‘Very grateful’

Meanwhile, the IRD would have to discuss Latin America “bilaterally” with Shell, given the company’s interests in Venezuela outweighed BP’s interests in the region.

Despite the oil companies’ reservations, another £60,000 was provided to the IRD in 1964, for which British officials were “very grateful”. At this stage, future oil-funded projects in Algeria and the United Arab Republic were under consideration.

Secret oil subsidies to the IRD continued beyond 1964. As historian Athol Yates found, BP agreed in 1968 to fund broadcaster Sawt Al Saahil, a British covert radio station based in Sharjah (an emirate in the Gulf), to the tune of £3,000 for three years.

However, the extent to which Shell and BP funded British covert propaganda operations in the late and post-Cold War period remains unclear.

Shell and BP did not respond to requests for comment.

Independent journalist @theCanaryUK, @jacobinmag, @ColombiaReports , & International History Review.