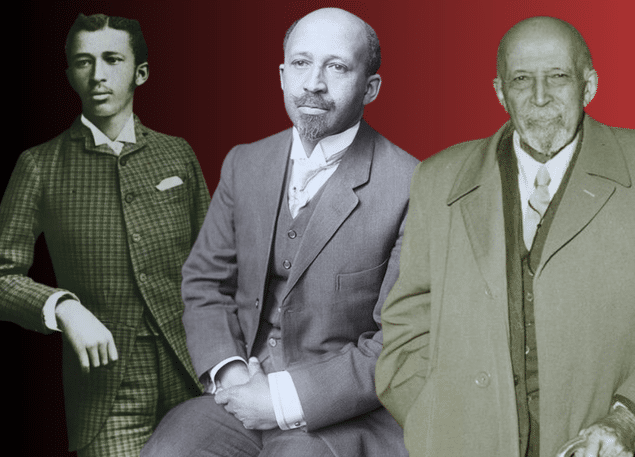

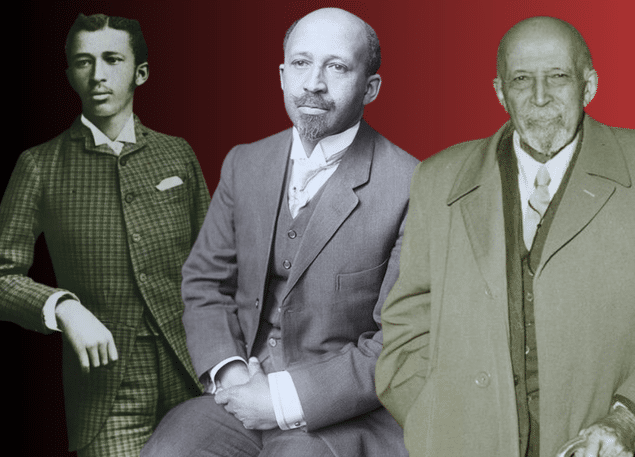

Photo composition showing William Edward Burghardt Du Bois at different stages of his life. Photo: Midwestern Marx.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

Photo composition showing William Edward Burghardt Du Bois at different stages of his life. Photo: Midwestern Marx.

By Carlos L. Garrido – Aug 5, 2023

Aristotle famously starts his Metaphysics with the claim that “all men by nature desire to know.”[1] For Dubois, if there are a people in the U.S. who have immaculately embodied this statement, it is black folk. In Black Reconstruction, for instance, Du Bois says that “the eagerness to learn among American Negroes was exceptional in the case of a poor and recently emancipated folk.”[2] In The Souls of Black Folk, he highlights “how faithfully, how piteously, this people strove to learn.”[3] This was a stark contrast with the “white laborers,” who unfortunately, as Du Bois notes, “did not demand education, and saw no need of it, save in exceptional cases.”[4]

Out of the black community’s longing to know, and out of this longing taking material and organizational form through the Freedman’s Bureau, came one of the most important accomplishments of that revolutionary period of reconstruction – the public schools and black colleges. It was these schools and colleges, Du Bois argued, which educated black leaders, and ultimately, prevented the rushed revolts and vengeance which could have driven the mass of black people back into the old form of slavery.[5]

This year marks the 120th anniversary of Dubois’s masterful work, The Souls of Black Folk. In this essay, I will be concentrating my analysis on the fourth chapter, titled “Of the Meaning of Progress,” where I will peruse how the subjects of education and progress are presented within a greatly racialized American capitalism.

The Tragedy of Josie

The chapter retells a story which is first set a dozen or so years after the counterrevolution of property in 1876. It is embedded in the context of the previous two decades of post-emancipation lynchings, second class citizenship, and poverty for those on the dark side of the veil.

Du Bois is a student at Fisk and is looking around in Tennessee for a teaching position. After much unsuccessful searching, he finally finds a small school shut out from the world by forests and hills. He was told about this school by Josie, the central character of the narrative. Along with a white fellow who wished to create a white school, Du Bois rode to the commissioner’s house to secure the school. After having the commissioner accept his proposal and invite him to dinner, the “shadow of the veil” fell upon him as they ate first, and he ate alone.[6]

Upon arriving at the school, he noticed its destitute condition – a stark contrast to the schools he was used to. The students, while poor and largely uneducated, expressed an insatiable longing to learn – Josie especially had her appetite for knowledge “hover like a star above … her work and worry, and she,” Du Bois says, “studied doggedly.”[7] While certainly having a “desire to rise out of [her] condition by means of education,” Josie’s quest for knowledge also went deeper than that.[8] It was, in a sense, an existential longing for education – a deeply human enterprise upon which a life-or-death struggle for being fully human ensued. “Education and work,” as Du Bois had noted in the Talented Tenth, “are the levers to uplift a people;” but “education must not simply teach work-it must teach Life.”[9] “It is the trained, living human soul,” Du Bois argues, “cultivated and strengthened by long study and thought, that breathes the real breath of life into boys and girls and makes them human, whether they be black or white, Greek, Russian or American.”[10]

Josie understood this well. She strove for that kind of human excellence and virtue the Greeks referred to as arete. But her quest was stopped in its track by the shadow of the veil; by the reality of poverty, superexploited labor, and racism which characterized the dominant social relations for the black worker.

A decade after he completed his teaching duties, Du Bois returned to that small Tennessee town. What he encountered warranted the questioning of progress itself. Josie’s family, which at one point he considered himself an adopted part of, had gone through a “heap of trouble.”[11] Lingering in destitute poverty, her brother was arrested for stealing, and her sister, “flushed with the passion of youth … brought home a nameless child.”[12] As the eldest child, Josie took it upon herself to sustain the family. She was overworked, and this was killing her; first spiritually, then materially. As Du Bois says, Josie “shivered and worked on, with the vision of schooldays all fled, with a face wan and tired,—worked until, on a summer’s day, someone married another; then Josie crept to her mother like a hurt child, and slept—and sleeps.”[13]

In his youth Du Bois had asked: “to what end” might “[we] seek to strengthen character and purpose” if “people have nothing to eat or, to wear?”[14] Josie’s insatiable thirst for knowledge required leisure time, i.e., time that is unrestricted by the labor one does for their subsistence, nor by the weariness and fatigue which lingers after. Aristotle had already noted that it “was when almost all the necessities of life and the things that make for comfort and recreation had been secured,” that philosophy and the pursuit of science “in order to know, and not for any utilitarian end… began to be sought.”[15] Josie’s quest for knowledge, her longing for enlightenment, was made impossible by capitalist relations of production, and the racialized form they take in the U.S. As dilemmas within her family developed, she was forced to spend every ounce of her energy on working to sustain the meagre living conditions of the household. Afterall, as Du Bois eloquently says, “to be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships.”[16]

On the Dialectics of Socialism and Western Marxism’s Purity Fetish

It is true, as Kant said, that “all that is required for enlightenment is freedom;” but it is not true that, while being necessary, “the freedom for man to make public use of his reason in all matters” is sufficient![17] This freedom presupposes another – the freedom to have the necessaries of life guaranteed for oneself. What good can be made of the right to free speech by the person too famished to think properly? What good is this right to those homeless souls with constricted jaws and clenched teach in the winter? The artifices intended to keep people down, as Kant calls it, are also material – that is, they refer not only to the absence of opportunities for civic and political participation, but also to the absence of economic opportunities for securing the necessities of life.[18]

The great writer can emanate universal truths from their portraits of individuals. Du Bois accomplished this with Josie, who is a concrete manifestation of black folk’s trajectory post-emancipation. In both Josie and black folk at the turn of the century, the longing to learn, the thirst for knowledge, is met by the desert of poverty common to working folk, especially those on the dark side of the veil, where opportunity doesn’t make the rounds. As an unfree, “segregated servile caste, with restricted rights and privileges,” it is not only the bodies, but the spirit and minds of black folk’s humanity which were under attack.[19] It is a natural result of a cold world – one that beats black souls and bodies down with racist violence, superexploitation, and poverty – that a “shadow of a vast despair” can hover over some black folk.[20] And yet, Du Bois argues, “democracy died save in the hearts of black folk;” and “there are to-day no truer exponents of the pure human spirit of the Declaration of Independence than the American Negroes.”[21]

A Universally Dehumanizing System

Although intensified in the experience of poor and working class black folk – especially those in the U.S. – the crippling of working people’s humanity and intellect is a central component of the capitalist mode of life in general. This was already being observed by key thinkers of the 18th century Scottish enlightenment (e.g., Adam Smith, Adam Ferguson, et. al.). For instance, in Smith’s magnus opus, The Wealth of Nations, he would argue that the development of the division of labor with modern industry created a class of “men whose whole life is spent in performing a few simple operations,” of which “no occasion to exert his understanding” occur, leaving them to “become as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become.”[22] “His dexterity at his own particular trade,” he argues, is “acquired at the expense of his intellectual, social, and martial virtues.”[23] “In every improved and civilized society,” Smith observes, “this is the state into which the labouring poor, that is, the great body of the people, must necessarily fall, unless government takes some pains to prevent it.”[24]

Writing almost a century later, and hence, having the opportunity of observing a more developed capitalist social totality, Marx and Engels saw that the degree of specialization acquired by the division of labor in manufacturing had even more profound dehumanizing and stupefying effects on the working class. “A labourer,” Marx argues, “who all his life performs one and the same simple operation, converts his whole body into the automatic, specialized implement of that operation.”[25] In echoing similar critiques brought forth by Ferguson and Smith, Marx explains how the worker’s productive activity is turned into “a mere appendage of the capitalist’s workshop,” and the laborer themself is converted into “a crippled monstrosity.”[26] It is a form of relationality which reduces working people to “spiritually and physically dehumanized beings.”[27] As Engels noted, capitalist manufacturing’s division of labor divides the human being and produces a “stunting of man.”[28] Alongside commodity production is the production of fractured human beings whose abilities are reduced to the activities they perform at work.

This mental and physical crippling of the worker under the capitalist process of production provides an obstacle not only to their human development, but to their struggle for liberation itself. No successful struggle against the dominant order can take place without educating, without changing the minds and hearts, of the masses being mobilized in the struggle. Education aimed at the acquisition of truth is revolutionary, that is why ignorance is an indispensable component of capitalist control. The “Socratic spirit,” as I have previously argued, “belongs to the revolutionaries;” it is in socialist revolutionary processes where education is prioritized as a central component of creating a new, fully human, people.[29] As Du Bois put it, “education among all kinds of men always has had, and always will have, an element of danger and revolution, of dissatisfaction and discontent. Nevertheless, men strive to know.”[30] “The final purpose of education,” as Hegel wrote, “is liberation and the struggle for a higher liberation still.”[31]

“How shall man measure Progress there where the dark-faced Josie lies?”

In the capitalist mode of life, this contradiction between the un-development of human life and the development of the forces of production has always gone hand in hand. From the lens of universal history, this is one of the central antinomies of the system. Progress of a certain kind has always been conjoined with retrogression in another. Du Bois says that “Progress, I understand, is necessarily ugly.”[32] He is quite correct in a dual sense. Not only has class society – and specifically, capitalist class society – always developed the productive forces at the expense of the un-development of human life in the mass of people, but also, when progress has been achieved in the social realm, it has never been thanks to the kindness and generosity of owning classes, it has never been the result of anything but an ugly, often bloody, struggle. As Fredrick Douglass famously said, “if there is no struggle, there is no progress.”[33]

However, it is the first sense in which Du Bois’s statement on the ugliness of progress is meant. He asks, “how shall man measure Progress there where the dark-faced Josie lies?”[34] What is our standard for progress going to be? Human life and the real capacity for human flourishing? Or the development of industrial technologies and the accumulation of capital? Under the current order, all metrics are aimed at measuring progress in accordance with the latter. As I have argued before,

The economist’s obsession with gross domestic product measures is a good example. For such quantifiability to take place, qualitatively incommensurable activities must transmute themselves into being qualitatively commensurable… The consumption of a pack of cigarettes and the consumption of an apple loses the distinction which makes one cancerous and the other healthy, they’re differences boil down to the quantitative differences in the price of purchase.[35]

This standard for measuring progress corresponds to a mode of social life where, as the young Marx had observed, “the increasing value of the world of things proceeds in direct proportion [to] the devaluation of the world of men.”[36] In socialist China, where the people – through their Communist Party – are in charge of developing a new social order, metrics are being developed to account for growth in human-centered terms. As Cheng Enfu has proposed, a “new economic accounting indicator, ‘Gross Domestic Product of Welfare,’”[37] (GDPW) is needed:

GDPW, unlike GDP, encompasses the total value of the welfare created by the production and business activities of all residential units in a country (or region) during a certain period. As an alternative concept of modernization, it is the aggregate of the positive and negative utility produced by the three systems of economy, nature, and society, and essentially reflects the sum of objective welfare.[38]

While forcing the reader to think critically about the notion of progress, it would be incorrect to suggest that Du Bois would like to entirely dispose of the notion. His oeuvre in general is deeply rooted in enlightenment sensibilities, in a belief in a common humanity, in the power of human reason, and in the real potential for historical progress. These are all things that, as Susan Neiman writes in Left is Not Woke, are rejected by the modern Heidegger-Schmidt-Foucualt rooted post-modern ‘woke left,’ and which stem, as Georg Lukács noted in his 1948 masterpiece, The Destruction of Reason, from the fact that capitalism, especially after the 1848 revolutions, had become a reactionary force, a phenomenon reflected in the intellectual orders by a turn away from Kant and Hegel and towards Schopenhauer, Eduard von Hartmann, Nietzsche, and various other forms of philosophical irrationalism.[39]

Instead of rejecting the notion of progress, Du Bois would urge us to understand the dialectical character of history’s unfolding – that is, the role that the ‘ugly’ has played in progress. He would urge us to reject the mythologized ‘pure’ notion of progress which prevails in quotidian society and the halls of bourgeois academia; and to understand the impurities of progress to be a necessary component of it – at least in this period of human history.

Du Bois would also urge us to understand that, while progress in the sphere of the productive forces has often not translated itself into progress at the human level, this fact does not negate the genuine potential for progress in the human sphere represented by such developments in industry, agriculture, and the sciences and technologies. Progress in the human sphere that is left unrealized by developments in the productive forces within capitalist relations ends up taking the form, to use Andrew Haas’ concept, of Being-as-Implication.[40] As Ioannis Trisokkas has recently elaborated, beyond simply being either present-at-hand (vorhandenseit) or absent, implication is another form of being; things can be implied, their being takes the form of a real potential capable of becoming actual.[41]

It is true, under the current relations of production, that the lives of people get worse while simultaneously the real potential for them being better than ever before continues to increase. This is the paradoxical character of capitalist progress. When a new machine capable of duplicating the current output in a specific industry is introduced into the productive process, this represents a genuine potential for cutting working hours in half, and allowing people to have more leisure time for creative – more human – endeavors. The development of the productive forces reduces the socially necessary labor time and can therefore potentially increase what Martin Hägglund has called socially available free time.[42] This is the time that Josie – and quite frankly, all of us poor working class people – need in order to flourish as humans. The fact that it does not do this, and often does the opposite, is not rooted in the machines and technologies themselves, but in the historically constituted social relations which mediate our relationship with these developments.

We can have a form of progress which overcomes the contradictions of the current form; but this requires revolutionizing the social relations we exist in. It requires a society where working people are in power, where the telos of production is not profit and capital accumulation in the hands of a few, but the satisfaction of human needs – both spiritual and material. A society where the state is genuinely of, by, and for the people, and not an instrument of the owners of capital. In other words, it requires socialism, what Du Bois considered to be “the only way of human life.”[43]

References

[1] Aristotle, Metaphysics, in The Basic Works of Aristotle (Chapel Hill: The Modern Library, 2001), 689 (980a).

[2] W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction (New York: Library of America, 2021), 766.

[3] W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, in Writings (New York: The Library of America, 1986), 367-368.

[4] Du Bois, Black Reconstruction, 770.

[5] Du Bois, Black Reconstruction, 770.

[6] Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 407.

[7] Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 406-407.

[8] Du Bois, Black Reconstruction, 766.

[9] Du Bois, “The Talented Tenth, In Writings, 861.

[10] Du Bois, “The Talented Tenth,” 854.

[11] Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 411.

[12] Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 411.

[13] Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 411.

[14] Du Bois, “The Talented Tenth,” 853.

[15] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 692 (982b).

[16] Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 368.

[17] Immanuel Kant, “What is Enlightenment,” in Basic Writings of Kant (New York: The Modern Library, 2001) 136.

[18] Kant, “What is Enlightenment,” 141.

[19] Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 390.

[20] Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 368.

[21] Du Bois, Black Reconstruction, 40; Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 370.

[22] Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations Vol II (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1910), 263-264.

[23] Smith, The Wealth of Nations Vol. II, 264.

[24] Smith, The Wealth of Nations Vol. II, 264.

[25] Karl Marx, Capital Volume: I (New York: International Publishers, 1974), 339.

[26] Marx, Capital Vol. I, 360.

[27] Karl Marx, The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 (New York: Prometheus Books, 1988), 86.

[28] Friedrich Engels, Anti-Dühring (Peking: Foreign Language Press, 1976), 291.

[29] Carlos L. Garrido, “The Real Reason Why Socrates Was Killed and Why Class Society Must Whitewash His Death,” Countercurrents (August 23, 2021): https://countercurrents.org/2021/08/the-real-reason-why-socrates-is-killed-and-why-class-society-must-whitewash-his-death/. In every revolutionary movement we’ve seen the pivotal role education is given – this is evident in the Soviet process, the Korean, the Chinese, Cuban, etc. As I am sure most know, even while engaged in guerilla warfare Che was making revolutionaries study. Education was so important that, as he mentioned in the famous letter Socialism and Man in Cuba, under socialism “the whole society… [would function] as a gigantic school.” For more see: Carlos L. Garrido and Edward Liger Smith, “Pioneros por el comunismo: Seremos como el Che,” intervención y Coyuntura: Revista de Crítica Política (October 11, 2022): https://intervencionycoyuntura.org/pioneros-por-el-comunismo-seremos-como-el-che/

[30] Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 385.

[31] G. W. F. Hegel, Philosophy of Right, trans. T. M. Knox (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978), 125.

[32] Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 412.

[33] Fredrick Douglass, Selected Speeches and Writings, ed. by Philip S. Foner (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1999), 367.

[34] Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 414.

[35] Carlos L. Garrido, “John Dewey and the American Tradition of Socialist Democracy, Dewey Studies 6(2) (2022), 87.

[36] Marx, Manuscripts of 1844, 71.

[37] Cheng Enfu, China’s Economic Dialectic (New York: International Publishers, 2019), 13.

[38] Enfu, China’s Economic Dialectic, 13.

[39] Susan Neiman, Left is Not Woke (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2023). Georg Lukács, The Destruction of Reason (Brooklyn: Verso Books, 2021). For more on the modern forms of philosophical irrationalism, see: John Bellamy Foster, “The New Irrationalism,” Monthly Review 74 (9) (February 2023): https://monthlyreview.org/2023/02/01/the-new-irrationalism/ and my interview with him for the Midwestern Marx Institute: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E4uyNEzLlRw.

[40] Andrew Haas, “On Being in Heidegger and Hegel,” Hegel Bulletin 38(1) (2017), 162-4: doi:10.1017/hgl.2016.64.

[41] Ioannis Trisokkas, “Being, Presence, and Implication in Heidegger’s Critique of Hegel,” Hegel Bulletin 44(2) (August 2023), 346: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/hgl.2022.3 Trisokkas here provides a great defense of Hegel from Heidegger’s critique of his treatment of being.

[42] Martin Hägglund, This Life (New York: Pantheon Books, 2019), 301-304.

[43] W. E. B. Du Bois, “Letter from W. E. B. Du Bois to Communist Party of the U.S.A., October 1, 1961,” W. E. B. Du Bois Archive: https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b153-i071

Carlos L. Garrido is a Cuban American philosophy instructor at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. He is the director of the Midwestern Marx Institute and the author of The Purity Fetish and the Crisis of Western Marxism (2023), Marxism and the Dialectical Materialist Worldview (2022), and the forthcoming Hegel, Marxism, and Dialectics (2024). He has written for dozens of scholarly and popular publications around the world and runs various live-broadcast shows for the Midwestern Marx Institute YouTube. You can subscribe to his Philosophy in Crisis Substack HERE.