The head office of BP in London. Photo: Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

The head office of BP in London. Photo: Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

By John McEvoy – Jul 19, 2023

Documents reveal how the oil company offered to finance Bogota’s military as it was killing opponents during the 1990s and collaborated with a general accused of kidnap, torture and murder, John McEvoy reports.

Files unearthed exclusively by Declassified in Bogotá, Colombia’s capital, shine a new light on British oil giant BP’s financial arrangements with the Colombian military during the 1990s.

At the time, the Colombian armed forces were one of the worst abusers of human rights in the Western hemisphere.

The documents show how BP not only offered to finance the military units operating around its oil sites in the department of Casanare, but also proposed funding Colombia’s “national defence activities” across the country.

On top of this, the files demonstrate how in 1994 BP collaborated with General Álvaro Velandia Hurtado, then the commander of the Colombian army’s notorious 16th brigade, on “conflict resolution” in Casanare.

An expert in military intelligence, Velandia has been accused of involvement in a series of brutal human rights abuses including the kidnap, torture and murder of a social activist in 1987, and collaboration with a Colombian death squad.

2 Billion Barrels of Oil

During the late 1980s, BP adopted a new “frontier” strategy of high-risk, high-reward oil exploration, with the objective of reversing a steady decline in its oil reserves.

The strategy would lead BP to Colombia, whose economy was liberalising within a context of spiralling political violence.

In the name of fighting Colombia’s guerrilla insurgencies, the Colombian military was engaged in the wide scale repression of the country’s social movements, often with the assistance of paramilitary organisations.

In 1991, BP announced it had struck oil in Casanare, traditionally a cattle ranching region situated roughly 100 miles north-east of Bogotá. It would prove to be BP’s largest oil discovery for over two decades, and its largest ever find in Latin America.

Unsurprisingly, a discovery of this scale caught the eye of the U.K. government.

In January 1992, U.K. Trade Minister Tim Sainsbury met John Browne, a managing director and later chief executive of BP. Over lunch, Browne described BP’s discovery in Colombia as “major,” adding that “reserves were unlikely to be less than 2 billion barrels of oil.”

For his part, Sainsbury promised that the “FCO [Foreign Office], and the British ambassador in Bogota, would do anything we could to help BP operate smoothly in Colombia.”

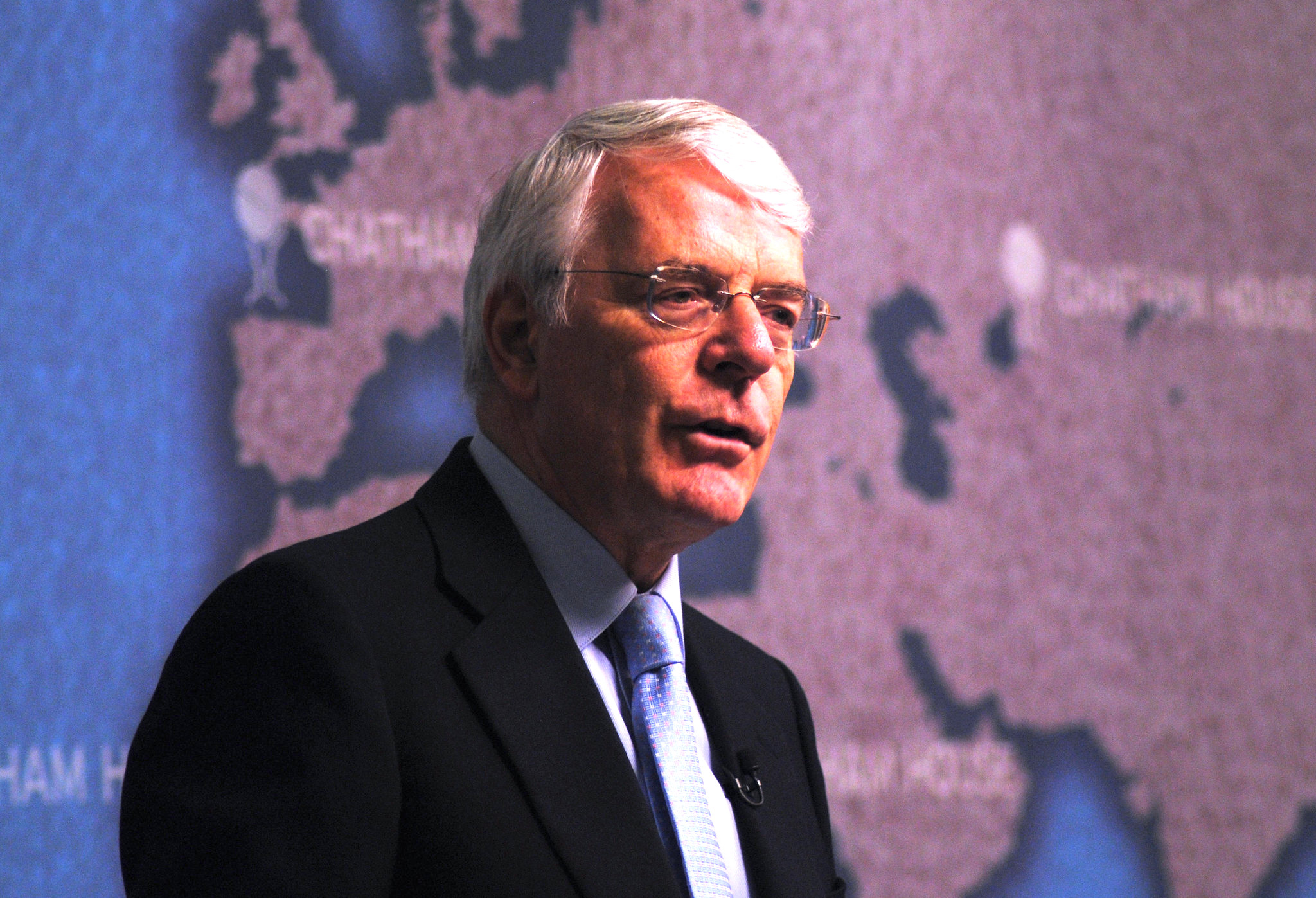

Later that year, John Major paid an official visit to Colombia, the first sitting U.K. prime minister to ever visit South America, and he went to see BP’s oil sites in Casanare.

BP’s oil discovery in Colombia would “revitalise our relationship with Latin America as a whole,” Major declared.

BP’s Financial Arrangements

Once BP had struck oil in Colombia, securing the oil fields became a priority for the company.

During the 1980s, the National Liberation Army (ELN), one of Colombia’s guerrilla organisations, had started targeting U.S. multinational Occidental Petroleum’s oil infrastructure in Arauca (a neighbouring department of Casanare) with a bombing and kidnap for ransom campaign.

According to one Occidental Petroleum executive, the guerrillas blew up the company’s pipeline 460 times between 1985 and 1997.

BP didn’t want to suffer the same fate as Occidental.

While funding “community projects” in Casanare, BP developed a security strategy which involved financing and collaborating with the Colombian military.

The new documents show that, in January 1993, BP’s head of Western-Hemisphere South, David Harding, wrote a letter to Colombia’s minister for mines and energy, Dr. Guido Nule Amín.

Harding thanked Amín for the “opportunity… to meet” at the presidential palace in Bogotá earlier that month. However, he expressed concern about the Colombian government’s request “to make advance tax or royalty payments” on its oil activities, noting the company’s “continued active involvement in community affairs and support of the Casanare military forces.”

Those military forces likely referred to the Colombian army’s 16th Brigade, a specialist force created in 1992 to protect oil interests and which is now linked to a series of human rights violations.

Rather than pay advance tax or royalty payments, Harding proposed an “instalment loan” to “assist the Colombian government at this difficult time.”

He offered up to $10 million “as a military or police loan for activities that specifically serve to reinforce the support and defence of our current operations in the Cusiana area,” where BP’s main oil sites were located.

An additional $5 million was offered “to reinforce the work developed by the community affairs department in the Cusiana area.”

‘National Defence Activities’

On top of this, Harding offered a loan of $3 million “for national defence activities, as deemed appropriate by the Colombian government.”

BP’s financial arrangements in Colombia thus went further than funding the armed forces surrounding its sites of operation, extending to security operations nationwide.

At this time, the Colombian armed forces were engaged in some of the most egregious human rights violations in the Western hemisphere.

According to the Andean Commission of Jurists, in 1993,

“of the political murders in which a perpetrator could be identified…, approximately 56 percent were committed by state agents, 12 percent by paramilitary groups allied with them, 25 percent by guerrillas, and 7 percent by private individuals and groups linked to drug-trafficking.”

In other words, during the year that BP offered to help fund Colombia’s national defence activities, the Colombian military and associated paramilitary groups were responsible for 68 percent of all political killings in the country.

Significant Funding

In the following years, it became clear that BP had provided significant funding to the Colombian armed forces.

The Colombian government found that BP paid $312,000 to the 16th Brigade between May 1996 and August 1997.

In a series of articles written by journalist Michael Gillard, it was revealed that BP also contracted a private security firm named Defence Systems Limited to train the Colombian police in counter-insurgency tactics.

BP’s close relationship with the Colombian military reportedly continued well into the next decade. According to an investigation by Colombian Senator Iván Cepeda in 2015, a group of oil companies including BP continued to fund the 16th Brigade throughout the 2000s.

‘Macabre Alliance’

The documents also shine a new light on BP’s military associates in Colombia.

In February 1994, Phil Mead, BP’s operations manager in the country, wrote a letter to Brigadier General Álvaro Velandia Hurtado to thank him for his “special collaboration in conflict resolution with the El Morro Community.”

Mead continued:

“Your presence at the talks, as a representative of the Armed Forces, guaranteed an atmosphere of respect and cordiality.”

One month prior, the El Morro Association, a community organisation in Casanare, had launched its first civic strike against BP to protest against the company’s failure to provide jobs and meaningful social benefits to the region. For two weeks, activists formed a roadblock designed to prevent any equipment from reaching BP’s sites in Casanare.

Shortly after, the activists began to receive threats. Many were subsequently killed. Carlos Arregui, a peasant union leader who was involved in the roadblock was gunned down by two assassins in April 1995 in front of his children.

Before he was killed, Arregui had placed blame directly on BP for the heightened repression in Casanare.

Arregui’s wife recalled that “he always said the oil company was behind the threats,” while his son, Rubiel, denounced the “macabre alliance” among the oil companies, the army’s 16th Brigade and paramilitary death squads in the region.

However, no evidence has emerged that BP was involved in these threats.

Kidnap, Torture & Murder

The function of General Velandia’s presence in meetings with the El Morro Association was seemingly one of intimidation rather than meaningful conflict resolution.

Indeed, Velandia is linked to a series of brutal human rights violations in Colombia, many of which pre-date his collaboration with BP.

In 1983, the Colombian attorney general found evidence of links between Velandia and Death to Kidnappers (MAS), a paramilitary death squad which was funded by the likes of drug kingpin Pablo Escobar.

The same year, Velandia was accused of involvement in the attack on, and detention of, a trade unionist named Armando Calle.

In 1991, three years before BP began collaborating with Velandia, a Colombian sergeant testified that Velandia had been responsible for the forced disappearance and killing of Nydia Erika Bautista, a Colombian social activist and M-19 member, four years prior.

M-19 was a Colombian urban guerrilla movement, of which Colombia’s current president, Gustavo Petro, was also a member.

On Aug. 30, 1987, Bautista brought her son to Bogotá to be baptised and take his first communion. In the afternoon, she was “approached by several armed men and forced to get into a Jeep.”

She was not seen again until her body was exhumed and identified in 1990, exhibiting evidence of torture and possible sexual assault.

In 1995, Velandia was dismissed from his military duties for his role in Bautista’s murder. The prosecutor, Hernando Valencia Villa, concluded that Velandia “knew and approved of his subordinates’ plans to forcibly disappear and kill captured guerrilla Nydia Erika Bautista, a crime he also failed to investigate.”

The dismissal was issued by executive order, and was the first time in Colombian history that a serving general was dismissed for human rights violations. Despite the high-profile nature of the case, Velandia’s prosecutor was forced to flee Colombia, fearing for his life.

In 2002, Velandia was permitted back to military service on a technicality. It was found that the statutory limit to review his case had expired, but the evidence of his responsibility in Bautista’s killing was not seriously disputed.

BP’s collaboration with figures like Velandia will likely raise fresh questions about the company’s security strategy in Colombia.

Death Squads Threaten Colombian Human Rights Defender Darnelly Rodriguez Twice in two Weeks

‘BP Will Be Judged for its Crimes’

Carlos Arregui was not the only prominent social leader in Casanare to be targeted by paramilitaries allegedly linked to BP’s oil operations.

Gilberto Torres, a former leader of the Oil Workers Union (USO) in Casanare and employee of BP’s partner Ecopetrol, was kidnapped and tortured by paramilitaries in February 2002.

He was released 42 days later following an international outcry, becoming one of only two Colombian union activists to be abducted by paramilitary groups and survive to tell the tale.

Torres claims that oil firms BP and Ocensa (a joint venture owned by BP, Ecopetrol and others) were complicit in his abduction.

One of Torres’ kidnappers, paramilitary leader Josue Dario Orjuela Martíz, testified in court that the oil companies in Casanare had “asked us to execute this man… This man held too many shutdowns, too many unions, too many strikes.”

Declassified has, however, seen no evidence to substantiate these claims.

Torres spoke to Declassified about the latest revelations regarding BP’s operations in Colombia. He said:

“I am a faithful witness to the activities of the oil industry at that time, as well as a victim in terms of my human and fundamental rights on the part of the multinational oil companies, including Ecopetrol and BP.”

Torres added:

“To see the content of these documents will allow us to see, even in this period of history, how the capitalist and economic interests of BP – the jewel of the British crown – have prevailed over human rights, the environment, peasant communities, social organisations, trade unionists, and especially human life. With utopic hope, BP will be judged for its crimes.”

BP did not respond to a request for comment.

John McEvoy is an independent journalist who has written for International History Review, The Canary, Tribune Magazine, Jacobin and Brasil Wire.