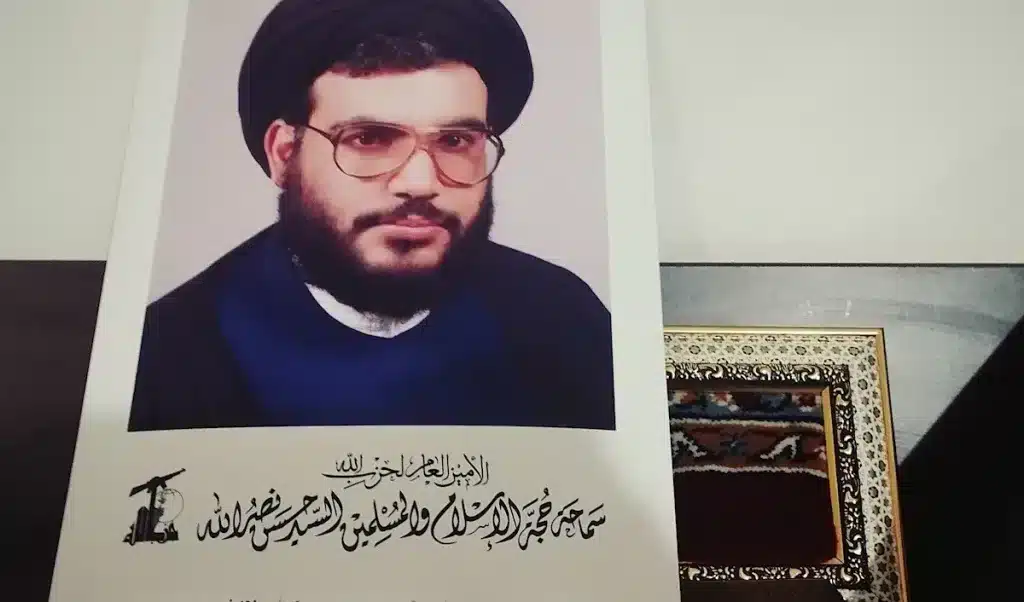

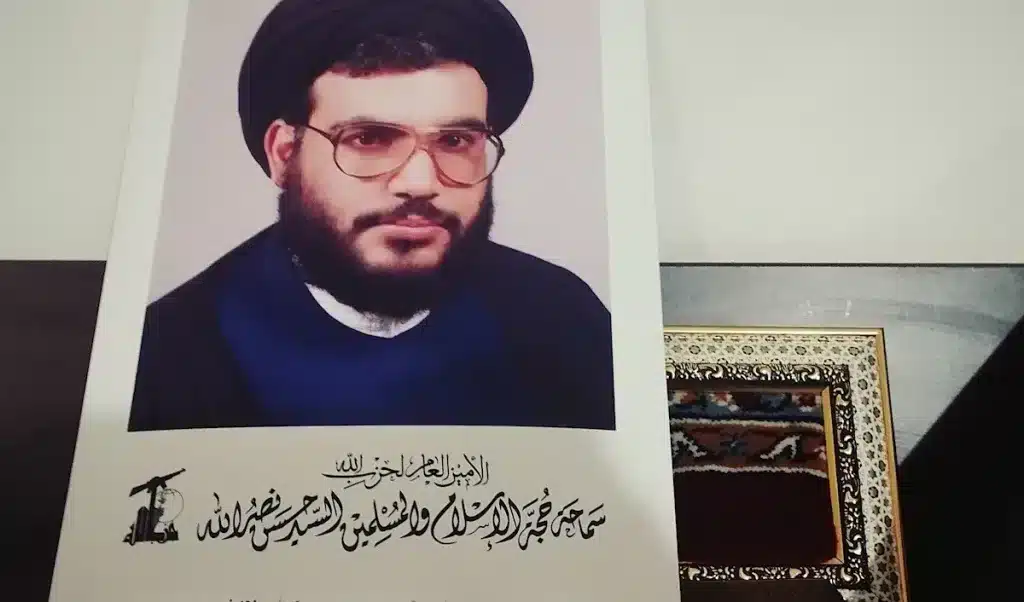

Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, Lebanese politician and former Secretary General of Hezbollah. Photo: al-akhbar/file photo.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, Lebanese politician and former Secretary General of Hezbollah. Photo: al-akhbar/file photo.

By Seif Da’Na – Sep 27, 2025

A year has passed, and our grief remains raw, unrelenting. In Palestine, we mourn the grandest of the nation’s martyrs with a sorrow that resembles that of “a mother whose child is slaughtered in her arms: her tears do not dry, her anguish does not rest.” It is also the grief of those who know, with certainty, that our tears will not cease, and our sorrow will not lift, until the day God grants us a world in which He truly dwells.

But Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah and his people did not just give to Palestine something for which we will forever be indebted. What they gave was far greater. Sayyed was one of the architects of the most pivotal transformation in the history of Palestinian resistance. He helped forge the strategic, regional, and political conditions for a defiant geopolitical space that now stands as a true resistance alternative. That achievement outweighs even the immense military support and human sacrifices offered by Hezbollah over four decades.

Such a transformation could never have taken shape under the suffocating grip of the official Arab order—an order that did not merely fail to support it, but actively worked to suppress and erase it. It was only with the emergence of a new reality, one forged by Sayyed Nasrallah and the Islamic Resistance in Lebanon, that these conditions became possible. And it was after the victory of May 2000 that the Palestinian resistance finally got on its feet; for the first time in decades, it stood upright.

In the Beginning, There Was May

On May 25, 2000, in the final, humiliating scene of a chaotic Israeli withdrawal, an episode that forever stained the reputation of every Zionist soldier, a defeated and broken officer named Benny Gantz locked the Fatima Gate in South Lebanon. Gantz, like his state, believed that an iron gate could somehow halt the consequences of such a bitter defeat.

But that day, and that defeat, the first of its kind in the history of the Arab-Zionist struggle, marked the foundation of the most significant shift and the most radical strategic transformation in the history of the Palestinian resistance and the wider Arab liberation movement. May 2000 was not simply a military victory. It was not just proof that resistance can triumph. Nor was it merely a source of renewed hope for Palestinians. It was the birth of a historic counter-movement in the region, one that took us back in time to before the Naksa and all that followed.

Under the leadership of Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, Lebanon was not yet fully liberated. But the horizon of Palestine’s liberation—long obscured—suddenly opened wide. For the first time in decades, the foundations of a true national liberation movement in Palestine began to take shape. Since the catastrophic separation between Egypt and Syria—and more precisely since June 1967—we had plunged, and been plunged, into the abyss of the “invincible enemy” ideology. That abyss swallowed the Arab population’s sense of self, distorted the understanding of our enemy and disoriented our view of the world. What followed was a long and painful descent: Camp David, Oslo, and Wadi Araba—each a milestone in the collapse of a region whose historical, civilizational, and cultural weight once held the potential to reshape the global order.

Then came Nasrallah. In May 2000, he charted an alternative path to Palestine. He held the hand of an entire nation—not just to pull it out of that abyss, nor simply to restore its self-confidence—but to lead it, step by step, to stand behind him at the Fatima Gate. That gate, which had seemed impossibly distant from the bottom of that ideological pit just months earlier, suddenly felt near. And through that gate, the Arabs saw it. The world saw it. Even the enemy saw that Palestine was close. Closer than they had dared to believe.

This was not only the most profound turning point in Palestine’s modern history, but it was the moment the Arab and Palestinian resistance, for the first time in generations, got up on its feet.

After the June 1967 War

Compared to other regional wars and civil wars with regional implications, the June 1967 War was not even a medium-scale conflict. It fell somewhere between a small and medium war in scope and structure. It lasted only six days, with casualties estimated at around 20,000. Even the geographic and military theater of operations was significantly smaller than in other wars: from Korea (1950–1953), to Vietnam (1955–1975), to the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), and even the October 1973 War.

The wars between India and Pakistan between 1965 and 1971, which unfolded in the same period as the June 1967 war, mobilized nearly 1.5 million troops on each side and were fought across territories more than 10 times the size of historic Palestine. Yet the academic, intellectual, and political attention given to these wars, while not insignificant, pales in comparison to the vast body of literature—military, strategic, ideological, and psychological—produced around the June 1967 Arab–Zionist war.

Most literature on the India–Pakistan wars was limited to military dimensions and, later, on nuclear strategy. The Korean War, arguably one of the most strategically significant conflicts since World War II, drew in China, the US, and the Soviet Union at a decisive turning point in the Cold War. It redrew Asia’s geopolitical map for over six decades, led to the division of Korea, and established US military presence in the region that continues to this day. Yet despite its scale—spanning a far greater geography, lasting three years, and killing over three million people—it became known as the “forgotten war,” eclipsed by the US war in Vietnam.

The 1967 war, by contrast, became the most mythologized military defeat in modern Arab history. The ideological and psychological aftermath of the defeat proved far more destructive than the war itself. The Zionist and Western propaganda machines, and even sectors of the Arab media, invested heavily in dramatizing the war’s meaning and exaggerating its consequences. Many Arab intellectuals and public commentators—whether out of conviction or ignorance—assessed the war in ways that ultimately served its real objectives: not only territorial or political gains for the Zionist entity and the Western alliance, but a strategic transformation of Arab self-perception. Instead of seeing it for what it was, an avoidable, containable defeat, they accepted its inflated version and treated it as irreversible. And in doing so, they helped disable any collective Arab effort to overcome it, to regroup, and rise to victory.

In 1967, the interests of the Zionist entity, the Western imperial system, and segments of the Arab ruling class aligned with striking clarity. Across the Arab world, regimes structurally tied to Western powers, and bolstered by networks of intellectuals, media outlets, and cultural elites, joined the effort to reshape the region and its political consciousness according to the narrative they had constructed around the war’s outcome.

The consequences of the 1967 war were not only exaggerated militarily. Its supposed economic cost was also inflated, deliberately and systematically, seemingly to pave the way for a new political reality, the so-called open-door policies, as Ali Kadri notes in The Unmaking of Arab Socialism.

This inflation was no accident. In a series of essays titled The Egyptian Economy in a Quarter Century: 1952–1977, it was claimed that “the losses of the Six-Day War ranged between 20 and 24 billion Egyptian pounds, nearly five times Egypt’s actual GDP in 1967.” Yet, according to the World Development Index, Egypt’s economy grew by 1% in 1968.

The war had caused limited physical damage to infrastructure, and military losses were swiftly replenished through Arab and Soviet support. As Kadri explains, “It is highly unlikely that such an economy would suffer losses of that scale to its infrastructure and GDP, and still manage to register positive growth the following year.” These fabrications were meant to rationalize the political shift that followed, one that led ultimately to Camp David.

What the war truly targeted—and partially succeeded in breaking—was the immense historical, cultural, and civilizational weight of the Arab world. While the region remains vital to Western imperial interests (oil, markets, arms), a glance at the map and a basic reading of history reveals that the Arab homeland, more than any other, holds the potential, if awakened, to inspire the resurgence of the entire Global South. No other nation, including India, Pakistan, Korea, or Vietnam, poses such a threat to the global order.

This vast alliance of Western, Zionist, and Arab interests that emerged in June 1967 did not simply exploit the moment of defeat—it had existed well before it. Since the Syrian–Egyptian union dissolution, this structure of interests grew deeper. The separation did not merely pave the way for the Naksa; it laid the cornerstone of an entire post-defeat era: one that produced a defeatist Arab rationality, a fractured political imagination, and a counter-doctrine saturated with Zionist language and colonial assumptions.

That separation marked the beginning of a new historical phase. One in which the revolutionary Arab doctrine that had dominated since the Nakba, rooted in anti-colonial struggle, Arab unity, and the liberation of Palestine, was steadily dismantled.

The idea of compromise (whether through a political solution, negotiations, or international resolutions) began to gain traction. It gradually replaced the goal of liberation, despite repeated attempts—many deceitful—not only to separate the two concepts, but to deliberately blur them.

In truth, the reassessment had already begun. Even before the Naksa, the collapse of the Syrian–Egyptian union triggered a wave of ideological revision across the Arab world—one that only deepened with the 1967 defeat. It struck at the heart of Arab political consciousness, shattered long-standing red lines, and laid the groundwork for the official discourse we hear today.

The concept of “compromise” began to replace the goal of “liberation.” Slowly, the language of negotiations, political solutions, and international resolutions replaced that of resistance and emancipation.

This discourse of compromise gave rise to new language, arguments, and rhetoric. In retrospect, it proved tragically effective, capable of deceiving public opinion and rallying support behind what was, at its core, a retreat.

From Student in Baalbek to Zionists’ Nightmare: Epic Journey of Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah

The PLO Flips Over

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), especially its dominant faction, became entangled in shifting Arab and international power dynamics, shaped by its interests, structure, connections, and social base. When the PLO adopted the “Interim Political Program” at the 12th Palestinian National Council in Cairo in 1974, the movement’s vision and understanding of national liberation was reduced to a single goal: political independence.

This was not a misunderstanding but the product of entrenched regional and global interests. From the outset, the liberation movement was divided along social and political lines, and these fractures fueled the internal tensions that have marked the PLO since its birth.

The change reflected a wider reality: national liberation movements evolve within larger geopolitical contexts, adjusting strategies and methods in response to shifting regional and global forces. The PLO’s transition from armed struggle to diplomacy, underscored by the time and place of the 1974 Cairo meeting, was emblematic of this shift.

The Palestinian crisis stemmed not only from internal rifts among elites and their competing programs, often invoked to explain the 2007 split, but also due to external conditions. It was shaped by how its leadership engaged with a new Arab regional order and an official Arab doctrine that favored the PLO elite, enabling them to dominate rivals. This trajectory, rooted in the aftermath of the 1967 defeat, explains why Oslo in 1993 was not the bottom, but another stage in a continuing decline. Reversing this course required nothing less than a regional upheaval capable of forging a new Arab framework and restoring the Palestinian struggle to its original path — standing upright once again after decades of being upside down.

The Resistance Provides New Footing

Then came Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah. He grasped, with unusual clarity, the need for an alternative geopolitical space for the Palestinian resistance, while also recognizing the immense cultural and civilizational weight of the Arab and Islamic world. He sought to revive and harness this legacy, transforming it into a weapon more powerful than arms. Remarkably, this task fell not to a major Arab state but to the leader of a resistance movement in Lebanon, the second-smallest Arab country and a country already divided over the very idea of resistance.

Sayyed Nasrallah’s mission was never limited to liberating occupied Lebanese land. He and his comrades built a genuine resistance movement, one that went beyond political independence and sought real sovereignty. They laid the groundwork for an Arab resistance project, creating a regional space that could help restore the Palestinian struggle to its pre-1967 trajectory.

In Palestine, Hezbollah’s role extended well beyond material and military support, which they did provide. Sayyed Nasrallah offered something greater: the creation of a geopolitical and ideological framework in which the resistance could grow and push toward Jerusalem. This foundation filled the vacuum left by the collapse of the PLO’s project, giving rise to an authentic, homegrown resistance model that inspired a new generation of fighters. The new resistance model was rooted in the cultural, civilizational, and historical legacy that had been obscured after the 1967 defeat.

Sayyed Nasrallah’s contribution was nothing short of a revolutionary revival of Arab and Islamic spirit. He mobilized history, culture, and identity in ways that even the wealthiest and strongest powers in the region could not. Unlike symbolic gestures of “liberating occupied land” at the expense of sovereignty, the project he led provoked wars and hostility precisely because it challenged not only colonial powers but also the Arab order born out of the 1967 defeat. And that confrontation continues today.