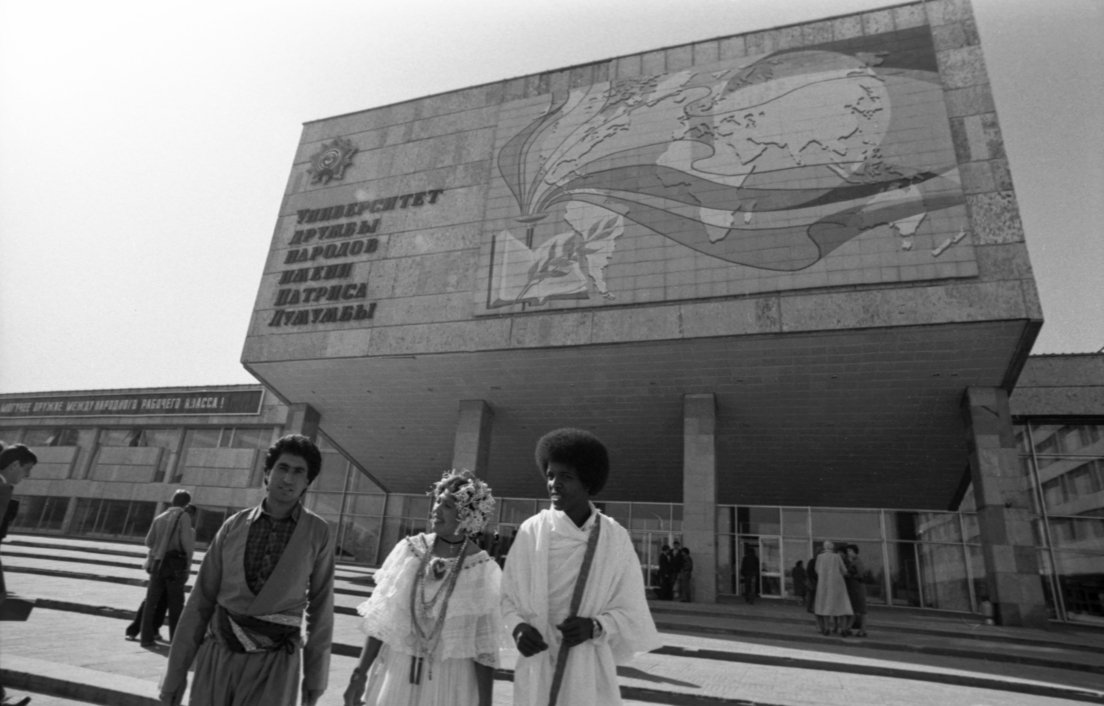

Photo of Patrice Lumumba Peoples' Friendship University's Humanities Faculty entrance in Moscow taken in 1979. Photo: Valeriy Shustov/Sputnik.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

Photo of Patrice Lumumba Peoples' Friendship University's Humanities Faculty entrance in Moscow taken in 1979. Photo: Valeriy Shustov/Sputnik.

By Oleg Yasinsky – Mar 24, 2023

Tens of thousands of citizens from all parts of the planet, graduates of the Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University in Moscow, never knew that, in 1992, during the government of Boris Yeltsin, profoundly anticommunist and pro-Western, the surname of the hero and martyr of the peoples of Africa, Lumumba, was removed from the official name of the university. Everywhere, all over the world, they continued referring to it as “Patrice Lumumba University.” In fact, most of the Russian neighbors of the university didn’t even know about this change.

This university was inaugurated in 1960, only 15 years after the Great Patriotic War [Second World War] with the goal of providing education to students from underdeveloped countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, thereby supporting these countries’ quest for a true, lasting sovereignty. The Western press, meanwhile, referred to graduates of the school as “terrorist and guerrilla cadres.”

In reality, the project of the Peoples’ Friendship University was much more subversive than that: it aimed to provide the countries colonized by the West, for the first time in their history, their own technical, agricultural, mining, and administrative specialists, replacing foreign elites and national oligarchies in top managerial positions that always require preparation and knowledge.

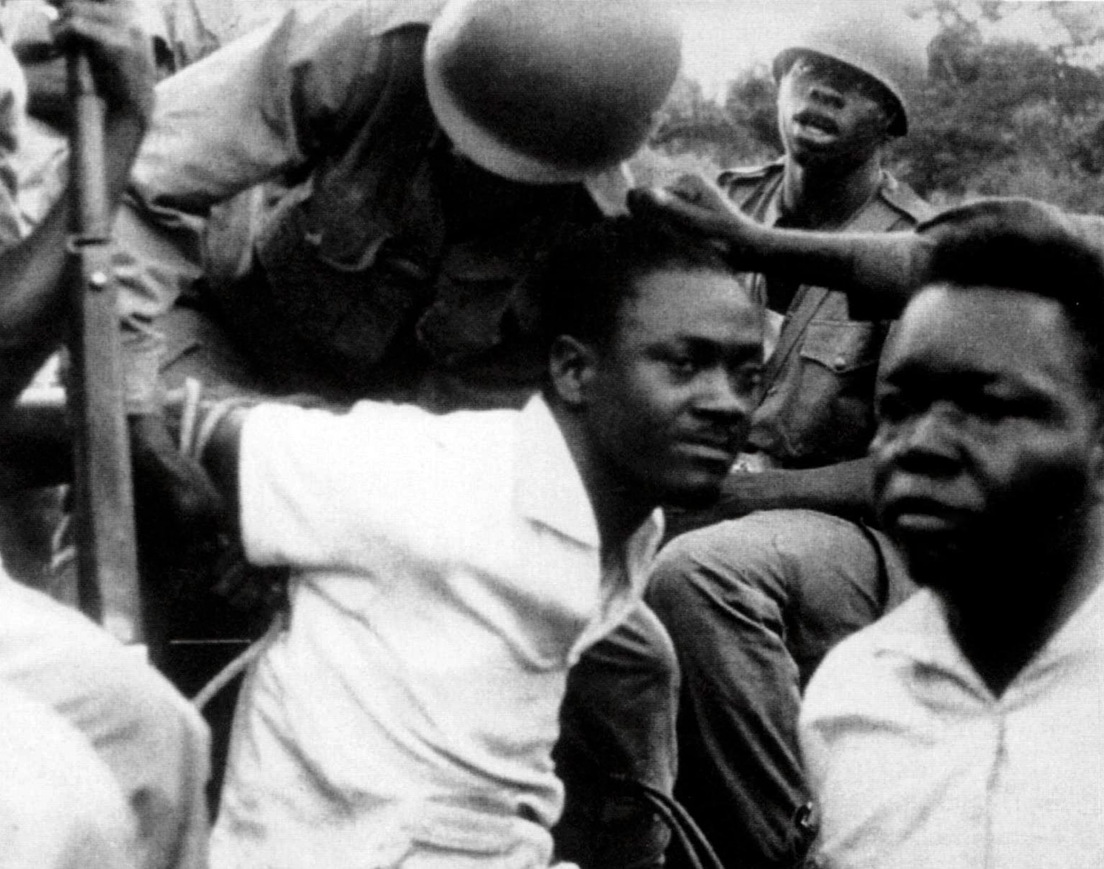

On February 22, 1961, one month after the CIA-ordered murder of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo by Belgian colonialists and their local mercenaries, the university took his name. Those were the years of the struggle of the peoples of Africa for their first independence, and the prime minister of Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Marxist Patrice Lumumba, was not just another revolutionary.

Belgium Returns Remains of Assassinated Congolese Leader Patrice Lumumba but What About Justice?

He was one of the most prepared, most determined, and most charismatic African leaders of the time. Lumumba was the African leader most feared by the US; if he were to have lived to consolidate his legacy, his leadership of the African revolutionary process could have changed the history of the continent. The Belgian colonizers utterly despised Lumumba.

Patrice Lumumba University, among other things, was an epicenter for one of the pillars of Soviet culture: internationalism. All the schools in the country had compulsory international friendship clubs where children learned the history, customs, music, dances and poetry of other countries. Foreign students were invited to these events to share, live together, and enjoy this mutual learning. The street where the residences for foreign students were built bears the name of Nikolai Miklukho-Maklai, a great Russian humanist and anthropologist, who at the end of the 19th century lived in Papua New Guinea, building a relationship of absolute equality with the Indigenous population and writing scientific papers in which he spoke with much love and admiration for those peoples. The Miklukh-Maklái papers were also part of the training of Soviet children. “Communist indoctrination,” some would say.

On March 23 of this year—that is, very recently—we received excellent news: the Russian Prime Minister, Mikhail Mishustin, announced that “a few hours ago, the Minister of Science and Education signed an order to return “Patrice Lumumba” to the name of the international university.

Although many were not aware that the name of Lumumba had been erased from the university’s official title a long time ago, a few were aware and demanded the return of the hero’s memory to its rightful place.

Our story is one. I am absolutely convinced that, between a student conversation in a Vladivostok school, an assembly of an Indigenous community in Mexico, or a ritual ceremony in a fishing village in South India, there is an absolute connection when events in one part of our reality condition or causes the others, at various points and different times at the same time. If we do not notice this, or if we simply do not know its mechanisms, it is not a reason to deny this reality. Nor does concern the “butterfly effect.” The idea of human groups that are capable of becoming a material force transforming realities, even if they seem static, makes any positive social experience highly contagious.

Our spirituality is built with the names and with the symbols that mark its paths and cardinal points. The liberation of the African countries from European colonialism would not be possible without the great Soviet victory over Nazi Germany. This process of African independence would be much more complex and lengthy without the active participation of Cuba, Fidel and Che, who, in turn, lived their previous process conditioned by their own realities, successes, and frustrations. It is not only that Patrice Lumumba returns to Moscow, but it is also Russia that returns to Africa, just as Lumumba does not represent, in ethical or historical terms, only the African continent, but all the struggles of all peoples to freely choose their future.

It is Russia that returns to the world, that for centuries has not had pro-European illusions and wants to build its own paths.

The role of Africa in our history is very special, not only because it is the cradle of humanity and the most looted and pillaged continent, with which the material well-being of the ‘first world’ was built. In Africa, in recent decades, all the absurdities of civilization have occurred: eternal wars and tremendous famines that are invisible to the media, a thousand human and cultural wonders that are not yet named in European languages, huge populations in total destitution, and bestial forms of organized crime, more scandalous and inhumane than in colonial times. One of the best portraits of our time, through the black mirror of Africa, is the documentary film Darwin’s Nightmare (miraculously it is on YouTube with various subtitles).

When speaking about Africa, we cannot fail to consider why, for Russians, the African continent is inseparable from their most beloved and important poet and the creator of the modern Russian literary language, Alexander Pushkin. His great-grandfather, Abram Petrovich Gannibal, born in the territory of what is now Cameroon, was a prisoner of the Turkish sultan, bought and brought to Moscow by a merchant as an exotic character. He was adopted by Peter the Great (who became his godfather), baptized in the Orthodox Church, and became the chief military engineer of the Russian Army, where he was appointed as a general.

A Russian child, seeing the new sign of the Russian Peoples’ Friendship University (RUDN), one day may ask his parents: “who is this man with such a strange name?” Thus, this Russian boy or girl may grow up accompanied by a new hero, and he will remember that this hero’s name is Patrice Lumumba, known to many in Latin America as “Patricio Lumumba.”

Oleg Yasinsky, is a Chilean-Ukrainian journalist, contributor to independent Latin American media such as Pressenza.com, Desinformemonos.org and others, researcher of indigenous and social movements in Latin America, producer of political documentaries in Colombia, Bolivia, Mexico and Chile, author of various publications, and translator of texts into Russian for Eduardo Galeano, Luis Sepúlveda, José Saramago, Subcomandante Marcos, and others.

(RT)

Translation: Orinoco Tribune

OT/JRE/SL