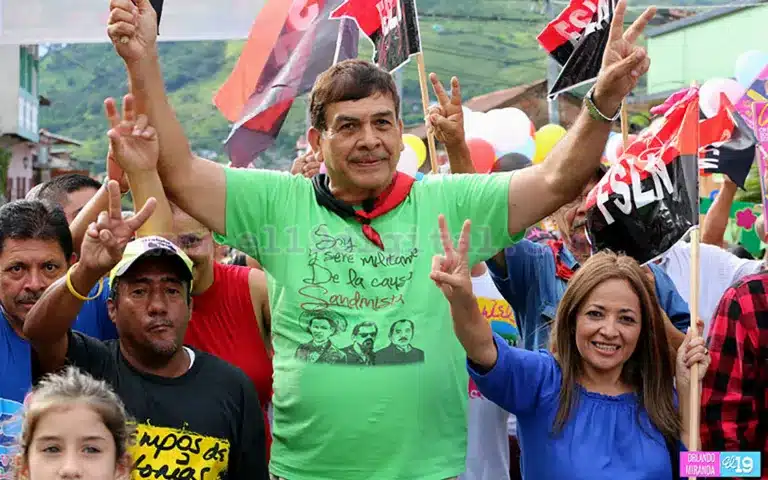

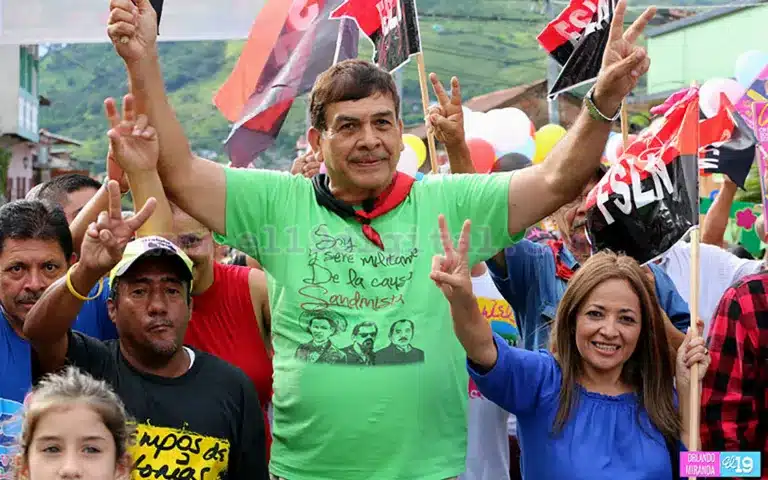

Sadrach Zelodón Rocha with his Vice Mayor Yohaira Hernández Chirino: Both have been subjected to personal sanctions in spite of a lack of evidence connecting them to deaths or other human rights violations during 2018. Photo: ondalocaini.com.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

Sadrach Zelodón Rocha with his Vice Mayor Yohaira Hernández Chirino: Both have been subjected to personal sanctions in spite of a lack of evidence connecting them to deaths or other human rights violations during 2018. Photo: ondalocaini.com.

By John Perry and Erik Mar – Jul 28, 2023

A Popular Mayor Who Worked to Improve Matagalpa’s Public Housing, Health, Transportation, Educational and Recreational Infrastructure Has Been Sanctioned for Human Rights Violations When There is No Compelling Evidence.

Nicaragua Is Among 40 Countries Targeted Under Cruel Sanctions Regime

On December 9, 2022, the government of the United Kingdom imposed sanctions on Sadrach Zelodón Rocha and Yohaira Hernández Chirino, the well-known Sandinista mayor and vice mayor of Matagalpa, Nicaragua, accusing both of “promoting and supporting grievous violations of human rights.”

The sanctions, subjecting both to “an asset freeze and travel ban,” also extended to members of their immediate families. As one of us has known Zeledón Rocha and the rest of his immediate family for more than 30 years, the accusations struck us mostly as false. Furthermore, if they turned out to be true, the punishments seemed strangely irrelevant given the magnitude of the crimes, since they almost certainly would have close to zero personal impact.

Unfortunately, as we explain, there are wider consequences for Nicaragua, regardless of the veracity of the accusations or the personal effects of the sanctions.

U.S. sanctions on Zeledón Rocha, along with two other municipal mayors, were imposed a year before, in 2021. The UK version dropped the other two and added his vice mayor, Yohaira Hernández Chirino, although she has never been sanctioned by the U.S., Canada or the EU. In spite of the apparent disagreements between the U.S. and UK over which public officials most deserve punishment, all were accused of human rights violations stemming their actions following the nationwide protests of 2018.

Among them, the U.S., UK and Canadian governments and the European Union have created a sanctions regime targeting approximately 40 different countries across the globe. Nicaragua has long been one of the countries targeted, first during the decade of the 1980s, and more recently, with escalating action since 2018.

While the economic sanctions are the best-known part of this regime, it also includes a huge list of thousands of individuals in different countries whose assets have been frozen or confiscated, their travel restricted and their ability to do business severely constrained.

Typically, names are added to a government’s sanctions lists with no prior warning or “due process.” In practical terms, the individuals affected are unable to challenge their inclusion, since it would require expensive legal actions in different countries with uncertain chances of success.

Once the UK sanctions were announced, we submitted a formal Freedom of Information request to the UK government asking for background information on the decisions affecting Zeledón Rocha and Hernández Chirino. It took several months to get a reply, and it only came on the day on which the UK government’s Information Commissioner had threatened to start legal proceedings against the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) because of its failure to respond.

The most important question, of course, was on what basis the decisions had been made. The FCDO declined to provide specific evidence, only stating that “Zeledón and Hernandez were designated for their involvement in violations of the right to life and right not to be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, by promoting and inciting serious human rights violations against protesters. Before the sanctions were imposed against Zeledón and Hernandez, evidence was collected from a variety of open sources, including civil society reports and media reports.”

Elsewhere in the FCDO response, they clarified that their actions relate solely to events in 2018, almost five years before the UK imposed its sanctions. Nicaragua’s three months of protests affected Matagalpa less than some other cities, but involved, in addition to relatively peaceful marches, an attempted assault on its town hall and police headquarters, the looting and burning of the municipal depot, and attacks on individual homes. A roadblock was also set up on the only road directly connecting the city to the Pacific half of the country, restricting the flow of food and other goods to and from the city.

We researched the human rights reports that may have been used by the FCDO, seeking to uncover hard evidence for the two classes of violations that prompted the UK government to impose sanctions. Perhaps the most detailed, and certainly one of the most internationally cited reports, is the one by the Grupo Interdisciplinario de Expertos Independientes (GIEI).

The GIEI was set up by the Organization of American States in May 2018, with the agreement of the Nicaraguan government, and reported the following December. Of the 500 pages in its report, only 12 are dedicated to the May 2018 events in Matagalpa, which are at the core of the accusations against Zeledón Rocha.

US Legally Owes Nicaragua Reparations, but Still Refuses to Honor 1986 Int’l Court of Justice Ruling

Hernández Chirino does not appear at all in the GIEI report, nor in any others we have been able to find. Her appearance in the sanctions list is therefore puzzling and appears to be a case of guilt by association. She most certainly does not appear to be directly implicated in any way to any human rights violations and was purportedly surprised, if not bewildered, by her inclusion in the sanctions list.

Returning to the accusations against Zeledón Rocha, the GIEI report lists three deaths in Matagalpa from the relevant time period: Luis Alberto Sobalvarro Herrera, Wilder David Reyes Hernández and José Alfredo Urroz Jirón.

The first was purportedly killed by a shot fired by the police—over whom neither Zeledón Rocha nor Hernández Chirino have any official responsibility. Both of the others were, in fact, Sandinistas and members of the governing party.

One was a municipal worker. Neither, then, was a likely target of the mayor or deputy mayor, and both were reported to have been victims of violent attacks by protesters.

The GIEI report does not attempt to link Zeledón Rocha directly to any of the three deaths. A subsequent petition by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which contains detailed allegations in the case of Sobalvarro Herrera, makes no mention of him either. It therefore appears that the evidence for Zeledón Rocha’s “violations of the right to life” is flimsy at best. The sanctions against him cannot therefore be due to this class of human rights violations.

It is important to note that it is typical of all the human rights reports of this period that deaths among Sandinistas, government officials or police, are often either unrecorded or wrongly added to the tally of deaths caused by the government.

For example, in addition to the two cases above, six other Sandinistas or government officials were killed in Matagalpa in 2018: Lenín Mendiola, Tirzo Ramón Mendoza Matamoros, Arán Molina, Holman Eliezer Zeledón, Luís Alberto Espinoza Trujillo, and Martín Exequiel Sánchez Gutiérrez. None was mentioned in the final GIEI report, nor, presumably, did the “group of experts” investigate them, even though they were widely reported elsewhere.

What then of the evidence for Zeledón Rocha’s violations of the “right not to be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, by promoting and inciting serious human rights violations against protesters”?

The sole piece of visual evidence linking him to any of them is a single photograph in the GIEI report that allegedly shows him with “shock groups” prior to May 11. Interestingly, none of those visible in the photo is armed, and none is wearing any sort of military gear or face coverings. In another photo purportedly showing the same “shock groups,” a woman is wearing shorts and sandals—hardly the sort of gear appropriate for paramilitary action. The report then goes on to cite an interview in which Zeledón Rocha was accused of “that day leading the [paramilitaries]” (p. 145).

That apparently sufficed as evidence, in spite of the multiple questions that might be raised. For example, Zeledón Rocha was never in the military, much less in any command position. During the 1980s, as a licensed civil engineer, he held positions in the ministries of housing and commerce, in the International Red Cross and in the Electoral Commission for the 1990 elections.

In 2001-2005, he served as mayor of Matagalpa, with the efficiency and transparency of his administration winning him plaudits from all sectors of Nicaraguan society prior to the FSLN’s return to national government in 2007. Since 2008, Zeledón Rocha has been mayor, and his administration has developed the city’s housing, health, transportation, educational and recreational infrastructure in the same framework of transparency and efficiency that marked his first term. His work has become difficult to ignore, even internationally. In 2017, he even won grudging praise from opposition outlet Confidencial (English translation here); Confidencial is normally dismissive of anything done by a Sandinista official.

His skill set seems conspicuously inappropriate for leading paramilitaries, especially given the plethora of other Sandinistas who have extensive military experience gained during the Contra war of the 1980s.

Another question that might be raised is the degree of responsibility that the “shock groups” allegedly directed by Zeledón Rocha had with “torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment” against the protesters. While the GIEI report notes that confrontations between the so-called paramilitary shock groups and the protesters occurred on May 11, after protesters had tried to assault the police station in the center of the city, it does not document any deaths, although it notes “an important quantity of persons wounded by mortars and stones” (p. 145).

Given that both groups were using stones and homemade mortars, the report perhaps wisely does not attribute responsibility, nor does it assign a specific number to that “important quantity of people.” Regardless, it seems that irrefutable evidence for Zeledón Rocha’s involvement in violations of human rights on May 11 does not exist.

The GIEI report states that 40 people were wounded during the May 15 confrontations between protesters and counter-protesters over a road block which impeded traffic from the Pacific side of the country, restricting the flow of supplies and food. Although there are several photographs of protesters with wounds (p. 150), Zeledón Rocha’s name is unmentioned.” Instead, blame for the wounded is laid at the feet of the national police, who allegedly fired with military-grade weaponry. As lacking in police experience or rank as he is with military experience, Zeledón Rocha is an unlikely scapegoat for these events, whatever one thinks of them, and the report does not make that connection.

In sum, the case for “promoting and supporting grievous violations of human rights” against Hernández Chirino, at least according to the GIEI report, is literally non-existent, and the case against Zeledón Rocha verges on non-existent. The stated rationale behind the sanctions, therefore, cannot possibly be the real rationale behind them. One might reasonably ask, then, what the real reasons might be.

It is hard to believe that those in the U.S. or UK governments charged with deciding who to sanction are aware of the subtleties of Nicaraguan politics and chains of command at the municipal level. The most straightforward and most probable explanation for the inclusion of Zeledón Rocha and Hernández Chirino in the sanctions list is their symbolic importance.

Zeledón Rocha in particular is widely known for his outstanding achievements in developing the region’s infrastructure, for the sheer competency of his administration, and for his willingness to work with all sectors of Nicaraguan society, regardless of their political persuasion. His efficacy and capabilities have earned him ever-increasing responsibilities, and he has therefore become an obvious target for those wishing to undermine or discredit the government.

We should also ask why sanctions are used at all. Furthermore, it is widely acknowledged, even by conservative think tanks such as the Cato Institute, that they are utterly ineffective.

Neither Zeledón Rocha not Hernández Chirino have any assets or interests in assets in any of the countries that have sanctioned them. Neither of them takes a holiday or travels professionally to any of those countries. Nor has extending the sanctions to their wider families affected anyone, as we have confirmed.

Both the U.S. and the UK governments must have known that the net effects would be close to zero. This is perhaps why the FCDO refused to answer the parts of our questions about how the decisions were made, what on-the-ground investigations took place, and how much the process cost. Both the UK and U.S. governments had the means and the reach to research all that we have covered in this article before imposing their sanctions: They did not consider it necessary or important to do so.

With this in mind, the inescapable conclusion is that the sanctions are a piece of political theater, for domestic consumption in the sanctioning countries. Both the U.S. and the UK government would apparently like to be seen as promoting “free and open societies around the world,” in the parlance of the UK Foreign Secretary. Unilateral and non-appealable sanctions are an approved means toward that end.

Underlying all of this, however, is the uncomfortable truth that this symbolic political posturing has real, material effects, perhaps not directly on those sanctioned, but on the overall climate of international aid, loans, and cooperation with a poor country still trying to recover from the Contra War and economic embargo of the 1980s, the violence of 2018 and the economic damage of the Covid-19 pandemic.

One reason to sanction individuals, such as mayors and government officials, is that sanctioning even one person in a country puts the whole country on a sanctions list (in the U.S., that managed by OFAC, the Office of Foreign Assets Control). It affects every kind of trade or financial transaction because businesses are immediately wary, not wanting to run afoul of national laws or get hit with fines. While to the average person such sanctions appear insignificant, in practice they are pernicious.

While the actions against individuals may be ineffective, wider economic sanctions are not. Nicaragua has not been as badly hit in this respect as neighboring Cuba or Venezuela, but it has seen the blocking of loans from the World Bank, several trade sanctions and only minimal medical aid from Western countries during the Covid crisis.

According to Nicaragua’s finance and housing minister, development loans have fallen from an average of more than $800 million before 2018 to less than $300 million since then, mainly because of U.S. influence over or blocking of finance from international institutions. Just as in the cases of Zelodón Rocha and Hernández Chirino, there is neither due process nor any appeal mechanism in which Nicaragua can contest these wider actions of foreign governments.

Furthermore, there is a growing body of opinion, reflected in the work and publications of the Sanctions Kill campaign, that these “unilateral coercive measures” are illegal in international law if they affect the enjoyment of human rights, such as freedom from hunger or access to health care, in the countries targeted. Neither the UK nor U.S. governments seem deterred either by this illegality or by the adverse effects of their sanctions on the human rights of poor communities in places like Nicaragua.

Erik Mar lived in Matagalpa, Nicaragua for several years and now lives in the United States. Erik can be reached at erikcmar@gmail.com.

John Perry is a writer based in Masaya, Nicaragua whose work has appeared in the Nation, the London Review of Books, and many other publications.

You must be logged in to post a comment.