The president of MAS, Grover García, holds a press conference recognizing the results of the August 17 elections in Bolivia. Photo: EFE.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

The president of MAS, Grover García, holds a press conference recognizing the results of the August 17 elections in Bolivia. Photo: EFE.

By Atilio Borón – Aug 19, 2025

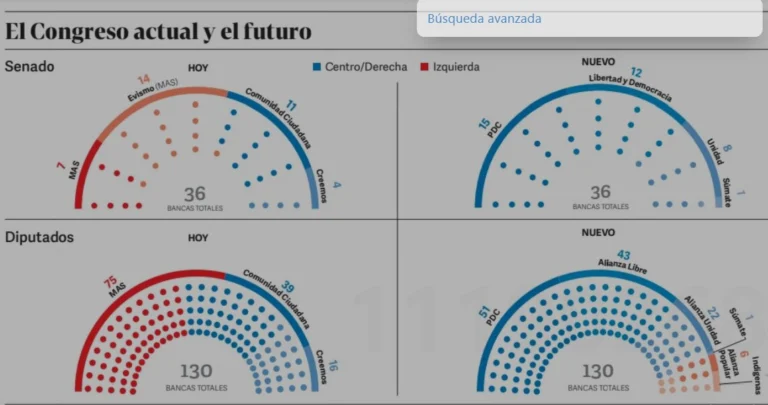

The image accompanying this note illustrates the profound changes in the National Assembly of the Plurinational State of Bolivia and the catastrophic nature of the MAS’s defeat in the August 17 elections. This marked the end of a cycle that began with Evo Morales’ victory in the presidential election of December 2005 and his entry into the Palacio Quemado in La Paz on January 22, 2006. A period, it should be emphasized, during which the electoral hegemony of the MAS was overwhelming, winning a succession of six elections with percentages that, except in one case, soared well above 50% of the votes. This supremacy at the polls was a reflection of the political hegemony of the MAS and the leadership skills of the undisputed leader of the popular movement, Evo Morales. In the nearly 14 years of his administration, interrupted by the fascist coup d’état on November 10, 2019, Evo’s governance radically and positively changed the face of Bolivia, leading many observers and media outlets to speak of the “Bolivian economic miracle.” Not only an economic but also a social and cultural miracle, areas where the advances were perhaps more spectacular than in the economic sector. However, this is not the place to examine that fascinating emancipatory process, its great achievements, as well as some of the most deficient aspects of those years. The urgency of the situation forces us to look toward the imminent.

It is therefore more productive to analyze what can be expected from such a spectacular collapse as the one that occurred last Sunday at the polls, but something that had been brewing almost since the moment Luis Arce Catacora assumed the presidency of the Plurinational State of Bolivia on November 8, 2020. This thesis, however, is questioned by Javier Larraín, director of the magazine Correo del Alba, who offers a more pessimistic view, and probably one more in line with reality. Larraín places the origin of this decline much earlier. He commented on this to Gustavo Veiga in an interview for Página/12: “The process of decomposition of the MAS began in 2013, 2014. We must remember that in 2019, it got the lowest vote with Evo at 47% and [before that] had lost a referendum whose results it did not recognize. Since then, what we have been seeing is a decline.”

Since that moment, an internal struggle for popular leadership and the direction of the process of change gained momentum. As Sacha Lorenti rightly points out in an article aptly titled “Preliminary Autopsy of the Elections in Bolivia” (because unfortunately, MAS, that great Bolivian popular movement, is dead), “Luis Arce’s government did everything within its power to try to destroy Evo Morales’ leadership: the theft of the MAS-IPSP acronym, the annulment of any possibility of participation with another acronym, the violent takeover of social organizations, the disqualification of Evo Morales, the assassination attempt on his life, the persecution and imprisonment of more than a hundred people who protested against the disqualification, and, as reported by Diario Red, payments to judges and members of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal to remove him from the electoral board.” This is true, but it cannot be overlooked that Evo, who was popularly known as “the big boss” during his presidential term, never fully digested the legal impossibility of being a presidential candidate in 2020 and always considered Arce—his star minister during the years of economic splendor, let us not forget that—an usurper, which is why he also did not spare harsh criticisms of Arce after he became the president.

A more balanced interpretation of this unfortunate conflict, which began as a fierce personal struggle for power and only later developed into a broader political and ideological divergence, is offered in an article by Álvaro García Linera on the eve of the Bolivian election. He described this fracture in very harsh terms: “On one side, a mediocre economist who happens to be president and who believed he could displace the charismatic Indigenous leader [Ev0] by banning him from elections. On the other hand, the leader who, in his twilight, can no longer win elections, but without whose support no one wins either. Who, in his revenge, is helping to destroy the economy without realizing that in this catastrophe, he is also demolishing his own work. The final result of this miserable fratricide is the temporary defeat of a historical project and, as always, the suffering of the humble who were never taken into account by the two brothers poisoned by personal strategies.”

Taking these background factors into account, especially that of a “miserable fratricide” that brings an end—or perhaps just a pause—to an ongoing revolution, Carlos Figueroa Ibarra, a professor at the University of Puebla, Mexico, is absolutely right in his enlightening analysis of the Bolivian elections. He asserts that both Rodrigo Paz Pereira, son of former president Jaime Paz Zamora (1989-1993), and his contenders Jorge “Tuto” Quiroga, with whom he will eventually contest in the runoff if latter does not withdraw from participating at the last minute due to his slim chances of winning, and Samuel Doria Medina, who came in third place in the first round, share the main lines that will define the course of the next government, almost certainly headed by Paz Pereira. This new neoliberal consensus, as Figueroa Ibarra correctly calls it, includes the “elimination of the plurinational republic, agroindustry as the heart of the Bolivian economy, legalization of genetically modified organisms, repression of social protest, privatization of state-owned enterprises, opening to transnational capital, elimination of fuel subsidies, and elimination of community land ownership.” Moreover, on the political front, it will include the pardon of the coup plotters Jeanine Añez and one of the leaders of the racist far-right and former governor of Santa Cruz, Luis Fernando Camacho, as well as the persecution of Evo Morales and Álvaro García Linera. In other words, a political nightmare.

In this unfortunate scenario, given a very painful defeat not only for the popular classes of Bolivia but also, I would dare to say, for all the peoples of Our America, Evo Morales’ triumphalist statements praising the 19.2% of null votes, which, according to him, project him as the leader of the opposition to the new reactionary regime, are surprising. That euphoria, which has as its undeniable foundation the loyalty of a significant part of the popular field to Evo’s directives, hides the ineffectiveness of the null vote, its practical sterility, except when it is the prelude to an insurrectional moment capable of challenging the constituted power, something that the author of this text does not see at this moment in Bolivia. Indeed, this possibility should not be ruled out if one considers the prolonged experience of struggle and the extraordinary combativeness of the Bolivian masses. Perhaps that confrontation between institutionalized power and the creative force of the street will occur, as Machiavelli always reminded us in his studies on the Roman Republic. However, those signs of popular insurrection are not currently seen in the prevailing political climate, nor do the existing correlation of forces in the fields of economy, politics, culture, and the military offer indications that something underground is heading toward a popular explosion, as Gramsci always warned. Meanwhile, the existence of a National Assembly in which the MAS has completely disappeared from the Senate and barely retains a tiny minority in Congress demonstrates that the null vote has served to help the right in building the two-thirds majority needed for the National Assembly to reform the Political Constitution of the State, nullifying the significant advances embodied in that brilliant constitution that emerged from the rise of the MAS. We know that, unlike the left, when the right has an opportunity, it does not waste time on philosophical debates or discursive wrangling. It acts quickly and lethally. For those who doubt this assertion, I advise them to examine the case of Argentina. Hopefully, a difference and better outcome will happen for Bolivia.

(Telesur)

Translation: Orinoco Tribune

OT/SC/SF

Atilio A. Borón is a Harvard Graduate professor of political theory at the University of Buenos Aires and was executive secretary of the Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO). He has published widely in several languages a variety of books and articles on political theory and philosophy, social theory, and comparative studies on the capitalist development in the periphery. He is an international analyst, writer and journalist and profoundly Latinoamerican.