Oxfam Report Details Obscene Wealth Inequality in India

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

January 18, 2022 (OrinocoTribune.com)—Oxfam, in its recently released report “Inequality Kills,” has exhibited what we have already felt over the course of the pandemic—the existing wealth divide among the rich and the poor got much worse globally. In the “India Supplement 2022” of the report, the organization turned its lens on the state of inequality in the “largest democracy in the world.” According to what is revealed by the supplement, India could very well be called the largest democracy of wealth inequality in the world.

In 2021, 84% of Indian households suffered a decline in their income while the number of billionaires in the country rose from 102 to 142, highlights the report published ahead of the Davos Agenda of World Economic Forum (WEF). This represents a 39% rise in the number of billionaires. The collective wealth of the richest 100 people in India reached an all-time record of $775 billion in 2021. From late March 2020—when nationwide lockdown was declared for the first time—to November 30, 2021, the wealth of Indian billionaires increased from $313 billion to $719 billion. On the other hand, in 2020 alone, over 46 million Indians fell into extreme poverty, representing nearly half of the new global poor according to the UN. The rate of poverty increase in India is higher than that in sub-Saharan Africa. At present, 50% of the population of India owns only 6% of the national wealth. In terms of income, the 142 billionaires earn more than what 550 million Indians earn together.

Among the billionaires, the one who made the most riches is Gautam Adani, owner of Adani Group that invests in multiple areas, from energy and mining to airports. About 20% of the collective wealth increase of the Indian billionaires corresponds to Adani’s increase of net worth. In 2020, his net worth was $8.9 billion; by the middle of 2021 it rose to $50.5 billion. In fact, according to real-time data, his net worth has crossed $90 billion. The net worth of another well-known billionaire, Mukesh Ambani of Reliance Industries, rose from $36.8 billion in 2020 to $85.5 billion in 2021. He is the richest person in India at present, with $98.3 billion to his name.

During the same period, successive—and ongoing—lockdowns led to a tremendous loss of livelihoods. In 2021, India registered the highest rate of unemployment. In urban India, unemployment has reached 15%, and this rate almost tripled in the age group 15-40. Women suffered around two-thirds of the job losses during the pandemic. However, according to many experts, these numbers do not properly reflect the situation on the ground. Most jobs in both urban and rural India are contractual, informal and insecure, which would make the real unemployment numbers much higher.

“The hundreds of millions of people who have suffered disproportionately during this pandemic were already likely to be more disadvantaged: more likely to live in low- and middle-income countries, to be women or girls, to belong to socially discriminated-against groups, to be informal workers,” says economist Prof. Jayati Ghosh, who is a member of the World Health Organization’s Council on the Economics of Health for All. The people who have suffered the most are also the most unlikely to have a voice in policy making, she points out.

RELATED CONTENT: Terror, Destabilization, Genocide: India’s Imperialist Proxy Role

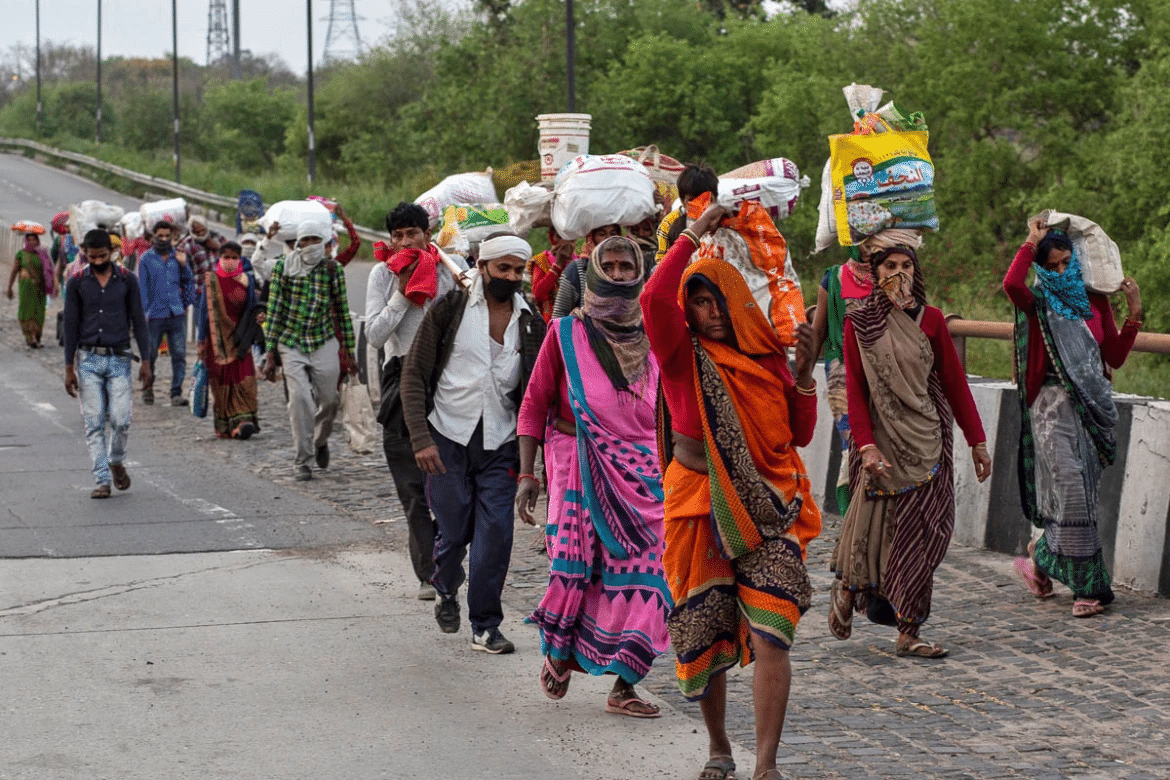

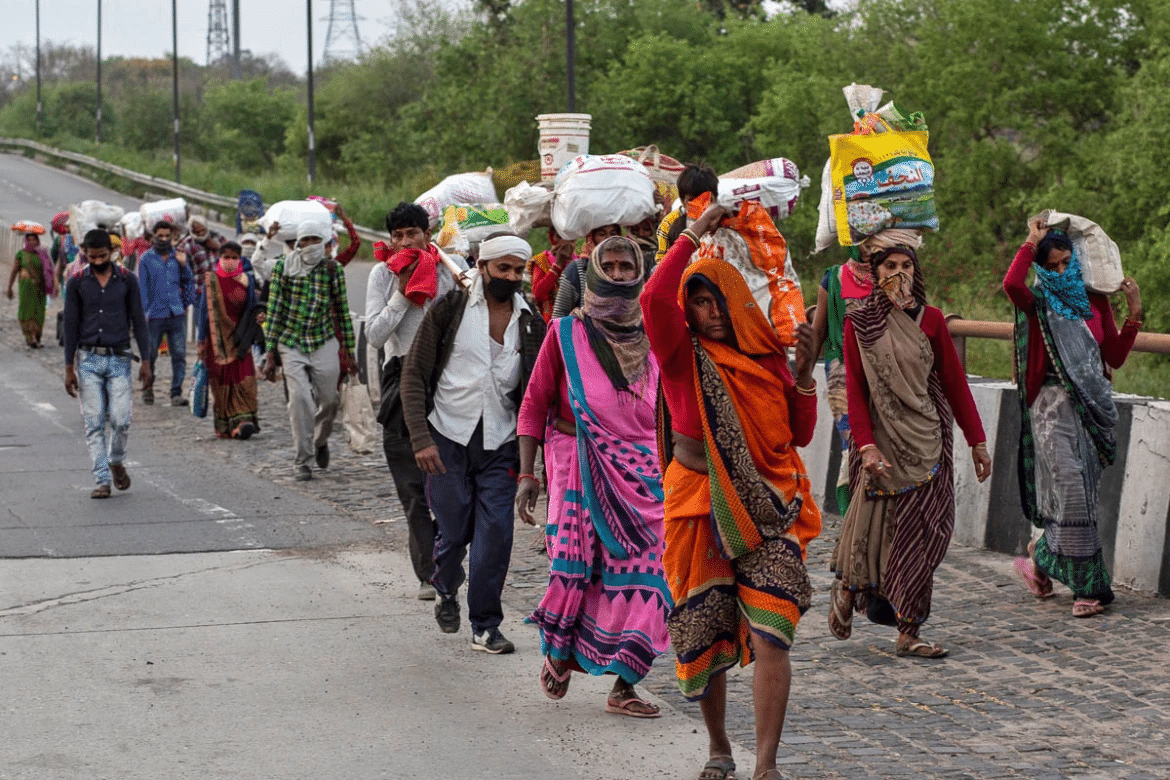

In India, the economic policies of the Narendra Modi government during the pandemic were certainly made by the richest, as exhibited by the policies themselves. The indirect revenue earned by the government of India has been increasing during the last four years, while corporate tax earning has been steadily decreasing. The indirect taxes, consisting of goods and services tax, land revenue, and taxes on petroleum products and electricity, are borne by the people of India, the vast majority of whom are poor. Compared to the pre-COVID period, taxes on fuel have been raised by 79%. The associated rise in prices of food items led to an overall inflation of 14.23% in November 2021. On the other hand, since 2016, the government, headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, eliminated the wealth and property taxes on the super rich, and reduced tax on corporations (corporate tax) from 30% to 22%. Even during the pandemic, the economic relief packages were made for the super rich and the corporations, while migrant workers, having lost their livelihoods, died on roads and railway tracks, trying to return to their villages of origin.

In the 2020-2021 budget, allocation in public health was reduced by 10%, and the education sector suffered a 6% cut. Only 0.6% of the budget was allocated for social security in the midst of the biggest health crisis and the worst economic contraction in living memory. The result is reflected in India’s COVID-19 numbers: 37.6 million cases and 487,000 deaths, although there is a general consensus in the country that these numbers should be multiplied by two to five times to get the real picture, as obfuscation and distortion of statistics is a common practice. Thus, inequality in wealth and income has really killed people in India, as wrote Prof. Jayati Ghosh in the foreword to the Oxfam report:

Over the past two years, people have died when they contracted an infectious disease because they did not get vaccines in time, even though those vaccines could have been more widely produced and distributed if the technology had been shared. They have died because they did not get essential hospital care or oxygen when they needed it, because of shortages in underfunded public health systems. They have died because other illnesses and diseases could not be treated in time as public health facilities were overburdened and they could not afford private care. They have died because of despair and desperation at the loss of livelihood. They have died of hunger because they could not afford to buy food. They have died because their governments could not or would not provide the social protection essential to survive the crisis.

Oxfam, in the introduction to its report, called such extreme inequality “economic violence,” and in the case of India, suggested that the government impose a 1% tax on the richest 10% in order to fund “proven inequality-busting public measures” such as higher investments in education, universal healthcare, and social security benefits. Prof. Ghosh called for systemic solutions, such as “reversal of the disastrous privatizations of finance, of knowledge, of public services and utilities, of the natural commons,” as well as economic policies like taxation of the super rich and the multinationals, and social policies like gender and racial equality. The Davos Agenda, on the other hand, is likely to suggest the opposite.

Featured image: Migrant workers in New Delhi, India, walking through the highways to return to their villages in Uttar Pradesh, after country-wide lockdown was declared in late March 2020. Millions of such workers, who are rural migrants to urban centers, were forced to walk hundreds of kilometers as a nation of 1.37 billion people was closed down on a four-hour notice. Photo: Danish Siddiqui / Reuters

Special for Orinoco Tribune by Saheli Chowdhury

OT/SC/JRE/SL

Saheli Chowdhury is from West Bengal, India, studying physics for a profession, but with a passion for writing. She is interested in history and popular movements around the world, especially in the Global South. She is a contributor and works for Orinoco Tribune.

You must be logged in to post a comment.