A meeting at the communal house of the women's collective Reunião Tramuco, Caracas, Venezuela. Photo: Bianca Pessoa.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

A meeting at the communal house of the women's collective Reunião Tramuco, Caracas, Venezuela. Photo: Bianca Pessoa.

By Ana Priscila Alves and Bianca Pessoa – May 24, 2024

Women in Caracas are building alternatives for political participation, autonomy, and fighting violence.

The presence of women spearheading local struggles on the ground is not something that happens only in Venezuela, but it has also been a recurring topic in political theory and practice for a long time around the world. Women’s everyday experiences are a key factor: they are rendered responsible for the care labor, making community life a necessity so that this care work can be as collective as possible.

The caring regard for the demands of homes, communities, and the many generations that need this care is fundamental for the organization. In Venezuela, women resist and are at the forefront of the political struggle, from everyday life to broader collective processes.

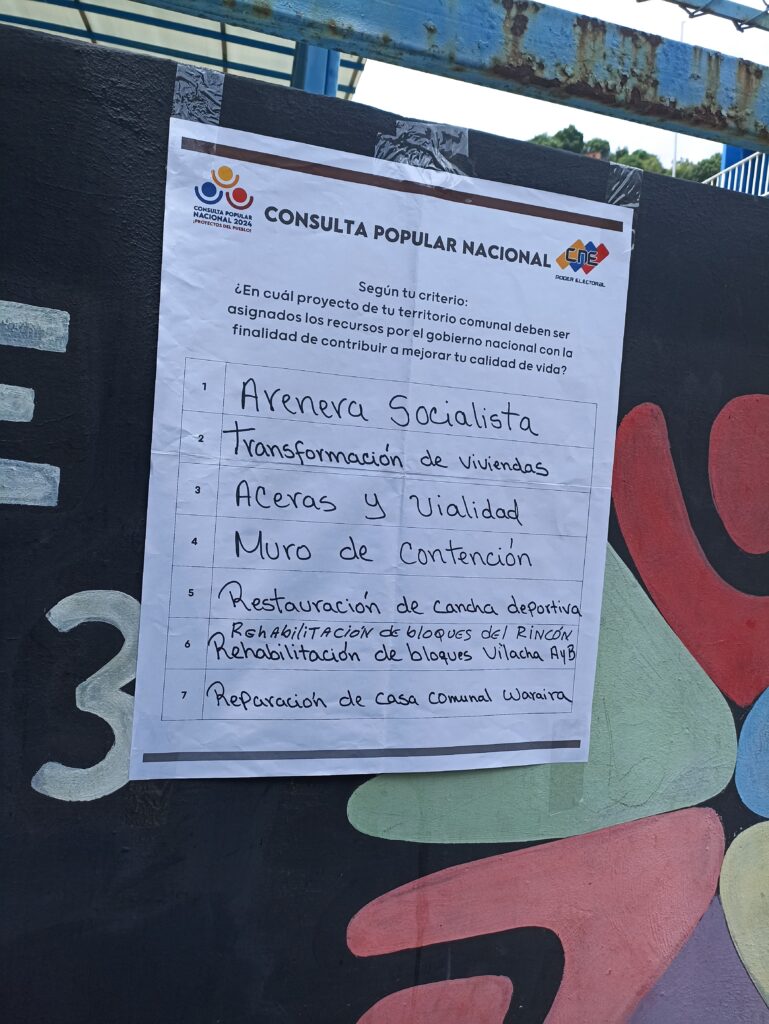

Here are some organizing and mobilization experiences by Venezuelan women building a society centered around life, free from violence. The accounts we share here have been gathered in April 18-21, during the Conference of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America – Peoples’ Trade Treaty (ALBA-TCP) and the National People’s Consultation ¡Proyectos del pueblo! held in more than 49,000 communal councils in 24 states across the country.

Women and public participation

Among the experiences of the Bolivarian revolution, we highlight the practices of people power. The communes are a form of social organization from the territories acknowledged by the Venezuelan government. Since the Organic Law of Communes was established in 2010, more than 3,000 communes have been registered. Each commune has its own structure, including communal councils (subdivisions of the larger area of the commune for self-organizing purposes). All of them meet at the highest level of local deliberation: the citizens’ assembly, where they map demands, define priorities, and organize the community.

On April 21, 2024, we attended a trailblazing process for the organization of people power: for the first time, people cast their ballots to decide which projects should be top priority in their own communes. Each commune presented seven projects, and each citizen had the right to vote for one of them to be executed with federal funds.

How a project should be executed is also important. The funds are transferred to the account of each commune, which manages everything: they make the assessments and build the necessary structure, with their own labor power, and prioritizing materials produced in the commune, whether hiring people from the commune or often counting on collective voluntary efforts, based on each one’s needs and capacities.

Both the government and communers estimate that women make up 80 percent of the people who are engaged in the movement, building practical communal processes. This participation was evident at voting spaces and centers. We were almost every time welcomed by sisters, local leaders who were connected to local demands and the local population. It is no coincidence that many of the projects were related to supplying drinking water, improving home structures and even communal offices, and building collective spaces, like amphitheater rooms.

In the communes, women ensure the sustainability of life in its broadest sense. Through self-organizing, they are currently working to hold the first national meeting of women communers. The meeting will be a fundamental milestone to promote those who are spearheading these processes, sustaining people power from the grassroots, and it will be a space where women will be able to formulate, together, the specific and different experiences they have while building what they have called communal feminism.

Llaneros Resist the Blockade: The Pancha Vásquez Commune (Part II)

Transformative experiences

Beyond the territory-specific realm, Venezuelan women are organizing in several fronts of struggle to ensure the sustainability of life. One of these experiences of community work is the Transformation, Women, Community (TRAMUCO) Cooperative Production Unity. The 45 women members of the collective, which was established in 2023, organize a community-based, participatory solid-waste management system in the parishes of Antímano, La Vega, Sucre, Altagracia, San Agustín, Coche, and Valle. The self-managed work these women conduct aims to repurpose glass, paper, and plastic, which are compacted and sold to the industrial sector or turned into new products that are traded and distributed in their communities.

During the implementation of the cooperative, an investigation was conducted in the territories to understand the systemic problems regarding each one’s solid-waste management. “These investigations involved local people and businesses. Then training and exchange sessions were held with women who work in the cooperative and the people from the communities,” TRAMUCO chair and resident of the La Vega parish Luz Daza explains. Luz says that the first challenge they faced was regarding incorporating the cooperative work: “Over time, we started to recognize ourselves as members of the organization, women who exchange their knowledge-wisdom and are part of this family.”

Barbara Quintero is 21 years old and is one of the members of the cooperative. During the meeting to create a statute for the cooperative, on April 19, she said “the cooperative is a space that dignifies the community with labor from a completely feminist management model.” She underscores the character of collective and individual development that such a process has by investing in training for the work and in women’s political education. “Each woman eventually finds herself, getting involved and developing herself by learning about each one’s reality,” she says.

The cooperative TRAMUCO is one of the projects that are part of the feminist organization Tinta Violeta, a member of the World March of Women in the country. In an interview to the Ministry of People Power for Women and Gender Equality granted on May 2, the chair of the organization said the work of Venezuelan feminist organizations empowers the public policy project known as Great Venezuela Women Mission (Gran Misión Venezuela Mujer, GMVM). In addition to projects such as TRAMUCO, Tinta Violeta is also in charge of research and action for women’s rights and against sexist violence.

The March 5 Commune and the Weaving Women Collective

Around 5,000 people live in the Eternal Commander March 5 Socialist Commune. Investing in the communal organization of life, women from the seven communal councils that make up the administration of the commune are organized in the Women and Gender Equality Management Committee. Based on the idea of communal feminism, the women in the territory reflect on their everyday needs for the sustainability of life in their communities and work in projects to ensure rights, protection, and education on gender-based violence and reproductive health. “When we talk about women’s networks, we are talking about the fabric we weave every day, one by one, but which are intertwined with other people’s fabrics, with other people’s threads and yarns, no matter how many kilometers they have between them,” the collective wrote on social media.

The Flower Route is one of the feminist communal policies organized in the March 5 Commune, in Caracas, and also in the communes Vencedores de Carorita, Estado Lara, and in Las 5 Fortalezas de Cumanacoa, in Sucre state. The three flowers, cayenne, sunflower, and bromeliad, are references for the three lines of the organization: women’s health care, fighting violence, and education and information. Women’s work in the Flower Route organizes the distribution of contraception and expands their knowledge on sexuality and protection. The organization also promotes communal feminist movement-building in regional meetings with women from the communities. Not only that, women who are victims of sexist violence find in the Women Weaving (Tejiéndonos Mujeres) Collective Communal House a center for meetings and spaces where they find services and emergency care, including psychological care and other necessary actions to make sure women and children are safe.

This set of grassroots initiatives that bring together the struggle for the sustainability of life from the ground and the building of people power in public policy management are some examples of the feminist power of Venezuelan women. Women build alternatives together from their own communities, from the lives of their sisters in their neighborhoods, from everyday needs. The radical organization of these women ensure changes in society and in life in the communes, not only for the women, but for everyone, showing how powerful communal feminism is as a pathway to build the world they want to live in.

(Capire)