The sanctions that Trump himself imposed in his first term destroyed the logistical bridges that their corporations would now need to operate efficiently. Photo: Adriana Loureiro Fernández / The New York Times.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

The sanctions that Trump himself imposed in his first term destroyed the logistical bridges that their corporations would now need to operate efficiently. Photo: Adriana Loureiro Fernández / The New York Times.

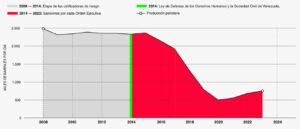

Against Venezuela between 2017 and 2020, Donald Trump’s first administration implemented the most aggressive sanctions regime in contemporary history on an oil-producing country. The design of this policy, far from responding to human rights concerns as officially alleged, attempted to paralyze the Venezuelan economy.

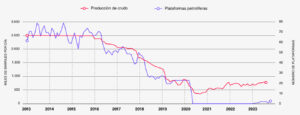

A study by Francisco Rodríguez on the subject documents that the fall in Venezuelan oil production accelerated from a 1% loss per month in January 2016–August 2017 to a loss of 3.1% per month for the following 16 months. Thus, if the financial sanctions of August 2017 had not existed, oil production would have remained stable. The sanctions resulted in an estimated loss of between 616,000 and 1.23 million barrels per day.

Trump 1.0: acceleration of Venezuelan oil decline

US Executive Order 13808 of August 2017 was the first direct impact against PDVSA’s financial circuit, restricting access to international financing and freezing assets under US jurisdiction. This measure specifically affected companies with access to external financing, which represented 46% of the loss of production attributable to sanctions.

The second blow came in January 2019 with the designation of PDVSA (Venezuela’s publicly owned petroleum company) as a sanctioned entity and the recognition of the parallel government of Juan Guaidó, which caused an additional contraction of 35.2% in production between January and March of that year.

The third phase, the secondary sanctions of February–March 2020 against Russian and Mexican companies in charge of international marketing, generated a fall of 55.7% between February and June 2020.

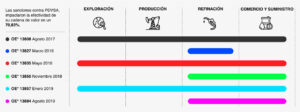

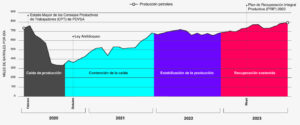

Impact of the sanctions imposed by Trump 1.0 on PDVSA’s value chain: graph made with public data. Photo: Misión Verdad.

The mechanism of destruction operated through multiple pathways. The confiscation of Citgo, valued at approximately US $8 billion, deprived Venezuela of US $900 million per month in dividends and the ability to acquire diluents necessary to process Venezuelan extra-heavy crude oil.

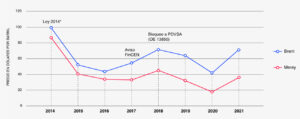

The price differential between Venezuelan Merey crude oil and Brent reached discounts of up to 40% in 2018, with sales prices of US $18 per barrel in 2020 compared to US $41 for the international benchmark.

Estimated differential between crude oil markers due to sanctions until 2021: graph made with public data. Photo: Misión Verdad.

President Nicolás Maduro revealed in September 2020 that Venezuela lost 99% of its oil revenues between 2014 and 2019, a fall that some analysts compared to that of an economy under conventional military conflict.

Stages of the United States attack on PDVSA until 2023: graph made with public data. Photo: Misión Verdad.

PDVSA’s value chain suffered an impact of 70.83% on its operational effectiveness. Sequential sanctions affected exploration, production, refining, and trade, restricting access to technology, spare parts, and specialized services. The withdrawal of service providers such as Halliburton, Schlumberger and Baker Hughes—limited to mere asset preservation operations—left the industry without preventive maintenance capacity. The number of operational oil platforms fell into direct correlation with production, showing that the collapse did not correspond to external management factors but to the material impossibility of operating under extreme financial and commercial restrictions.

Oil platforms and crude oil production in Venezuela: graph made with public data. Photo: Misión Verdad.

The progressive recovery of Venezuela

The Venezuelan response to the US siege configured a process of energy geopolitical reconfiguration with global implications. In 2020, the Venezuelan government, led by President Maduro, implemented the Comprehensive Productive Recovery Plan (PRIP), structured in four phases: containment of the fall, stabilization of production, sustained recovery, and growth.

Recovery of oil production in Venezuela: graph made with public data. Photo: Misión Verdad.

The vice president at that time, Delcy Rodríguez, emphasized in 2025 that “Venezuela’s oil and gas production is maintained, and in the process of recovery, with its own efforts, which is the path that should guide us, there is no other way.” In addition, she has defended the Venezuelan right to cooperation with friendly countries, particularly China, Russia, and Iran.

Official data from the Central Bank of Venezuela indicate that oil production grew by 18.23% in the first quarter of 2025, reaching levels above 800,000 barrels per day according to direct communications from PDVSA to OPEC. This recovery was developed through the activation of the Productive Councils of Oil Workers (CPTP), the rehabilitation of critical infrastructure, and the replacement of pipes in Lake Maracaibo. The Anti-Blockade Law of October 2020 created the legal framework for commercial operations under exceptional conditions, allowing the diversification of export routes to Asian markets.

Strategic cooperation with Iran was particularly crucial. The exchange of Venezuelan crude oil for Iranian gasoline, publicly documented since 2020, allowed the internal supply of fuels to stabilize while rebuilding national refining capacity. China, through the National Oil Corporation (CNP), and Russia, via Rosneft, maintained operations in joint ventures that became “islands of productivity” within the sector. These strategic partnerships made it possible to reduce dependence on Western markets and establish alternative marketing mechanisms, although with financial costs exceeding 30% as a result of secondary sanctions.

The operational recovery produced in measurable macroeconomic results. Venezuela’s GDP grew by 9.32% in the first quarter of 2025, marking 16 consecutive quarters of expansion and closing 2024 with an annual growth of 8.54%.

According to the Preliminary Overview of the Economies of Latin America and the Caribbean 2025, presented by the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Venezuela was one of the countries with the highest growth in the region in 2024 (8.5%) and 2025 (6.5%), far exceeding the regional average (2.3-2.4%). This trajectory, developed in parallel with the relative containment of inflation (at 130% in 2018) to double-digit levels today, shows that the Venezuelan economy managed to adapt operationally to the sanctions regime through the reconstruction of alternative marketing chains and the strengthening of South–South cooperation.

The strategy of de-dollarization of oil sales has been a direct response to evade the financial architecture of the OFAC, linking national production to an emerging power bloc that challenges the hegemony of the petrodollar.

Venezuelan oil: a vital part of a systemic competition

Last January, the National Assembly approved the Partial Reform Law of the Hydrocarbons Organic Law, an instrument that redefines the framework for participation in the Venezuelan oil sector. The reform maintains the public domain of the deposits while introducing mechanisms of contractual flexibility: it allows the participation of private companies domiciled in Venezuela in primary activities, establishes royalties of up to 30% and integrated taxes of up to 15%, and incorporates international arbitration clauses for dispute resolution. The maximum duration of joint ventures is set at 25 years, extendable for an additional 15, with the return of assets to the state at the end of the contracts.

This legislative reform acquires particular relevance in the face of the plans announced by the Trump administration after the US military attack on Venezuela of January 3, 2026, that resulted in the abduction of President Maduro and the first lady, Cilia Flores. Although the legislative reform seeks to attract investment, it establishes state control frameworks and fiscal conditions that prioritize sovereignty and the recovery of national operational capacity not delivery of assets.

The criminal episode created a conjuncture of uncertainty but did not alter some structural difficulties. Trump’s plans, classified as “a break with precedents to take control,” depend on a political and legal strategy and on the will of corporations that today look more suspiciously at geopolitical risks.

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio detailed a three-phase plan—stabilization, recovery and transition—that would include the US obtaining and selling Venezuelan oil and controlling the income in order to allegedly “benefit the Venezuelan people.” However, the viability of this scheme faces significant structural obstacles:

US sanctions, far from consolidating Washington’s energy hegemony, accelerated the diversification of Venezuela’s partners towards powers that compete directly with the United States globally.

Trump’s attempt to force PDVSA to act according to Washington’s interests collides with reality: Venezuelan oil infrastructure no longer depends exclusively on US technology. The presence of strategic partners in the Orinoco Belt and the current debts with non-Western creditors act as a natural brake. In addition, the sanctions that Trump himself imposed in his first term destroyed the logistical bridges that their corporations would now need to operate efficiently.

Beyond Trump’s statements, the international context adds an additional variable of complexity. China’s advances in technological and energy sectors has resulted in Beijing taking the lead in 57 of 64 critical technologies between 2019 and 2023, including renewable energy, semiconductor manufacturing, and quantum computing. This reality transforms the dispute over Venezuelan oil into a component of a broader systemic competition, where the control of conventional energy resources is strategic for global energy dynamics.

The final paradox lies in the fact that the “maximum pressure” exerted by Trump in his first administration generated the conditions for a reconfiguration of the Venezuelan oil sector that could hinder the objectives of his second administration. The diversification of strategic partners and the updating of the legal framework create a scenario that is made more complicated by a transformed operational reality.

Venezuelan oil, far from constituting an accessible booty for the US, has become an indicator of the emerging energy multipolarity, where unilateral coercion loses effectiveness when faced with a diversification of alliances.

It is a battle that has ceased to be a bilateral issue to become a significant chapter in the reconfiguration of global power.

From Blockade to Asphyxiation: the US War on Cuba Enters Its Most Brutal Phase

Translation: Orinoco Tribune

OT/CB/SL

Cameron Baillie is an award-winning journalist, editor, and researcher. He won and was shortlisted for awards across Britain and Ireland. He is Editor-in-Chief of New Sociological Perspectives graduate journal and Commissioning Editor at The Student Intifada newsletter. He spent the first half of 2025 living, working, and writing in Ecuador. He does news translation and proofreading work with The Orinoco Tribune.