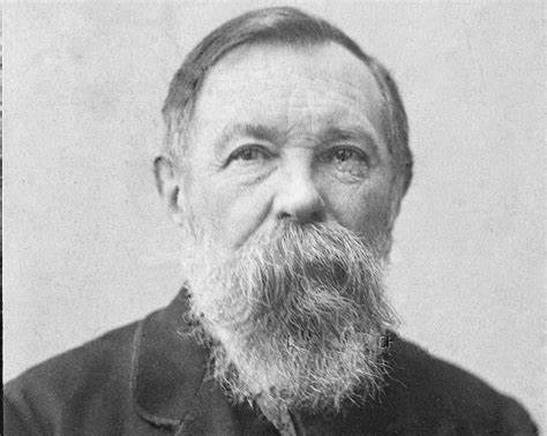

Friedrich Engels and the Dialectics of Nature. By: Kaan Kangal (Book Review)

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

By Carlos L. Garrido – Feb 8, 2022

For most Marxist scholars, the ‘break’ between ‘western’ and ‘soviet’ Marxism (and hence, the beginning of the ‘Engels debate’) occurs first in Georg Lukács’ famous sixth footnote of the first chapter in his 1923 History and Class Consciousness. Here, Lukács states that “Engels – following Hegel’s mistaken lead – extended the [dialectical] method also to knowledge of nature” (43). Instead, argued Lukács, the dialectical method should be limited to “historical-social reality” (ibid).

RELATED CONTENT: Interview with Frank Chapman about His New Book, Marxist Leninist Perspectives on Black Liberation and Socialism

What those who bank on this footnote forget, or are unaware of, is that Lukács comes to reject his own position to the point of “[launching] a campaign to prevent the reprints of his 1923 book” (55). Lukács had argued that his book was ‘outdated,’ ‘misleading,’ and ‘dangerous’ because “it was written in a ‘transition [period] from objective idealism to dialectical materialism’” (ibid). Additionally, he was quite explicit in arguing that “’[his] struggle against… the concept of dialectics in nature’ was one of the ‘central mistakes of [his] book’” (56). Further, in the posthumously published A Defense of History and Class Consciousness: Tailism and the Dialectic, Lukács says that “the dialectic could not possibly be effective as an objective principle of development of society, if it were not already effective as a principle of development of nature before society” (Ibid).

Lukács’ rectification should also show that he was the one that was following G. W. F. Hegel’s lead, for Hegel held that “organic nature has no history” (162). Therefore, “contra Hegel and Lukács, Engels is on the right track because he advances the view that nature has a history, and that it is a self-grounded totality,” i.e., that “dialectics applies to nature” (201-2).

Notwithstanding, Kangal argues that “the novelty of Lukács’ claim is overrated” (44). Before, during, and after the lives of Marx and Engels, debates concerning dialectics in general, and dialectics in nature in particular, had already been taking place in socialist theoretical circles across Europe. Instead of the orthodox origin story of the debate in Lukács’ footnote, Kangal “offer[s] an alternative history of the origin” of the debate which “goes back to the critical readings of Hegel among his pupils, most notably Adolf Trendelenburg and Eduard von Hartmann” (44).

After situating the origin of the Engels debate in the Hegel debate of the early 1840s with Trendelenburg, and the late 1860s with Hartmann, Kangal shows how this debate was rekindled during Marx and Engels’ lives in their debates with Eugen von Dühring and their friend Friedrich Albert Lange. Concerning the former, Engels “jokingly complained” to Marx while writing Anti-Dühring that

You can lie in a warm bed studying Russian agrarian conditions in general and ground rent in particular, without being interrupted, but I am expected to put everything else on one side immediately, to find a hard chair, to swill some cold wine, and to devote myself to going after the scalp of that dreary fellow Dühring (37).

Marx appreciatively noted in a letter exchange with Wilhelm Liebknecht the “great sacrifice” Engels made, “[postponing] an incomparably more important work [i.e., Dialectics of Nature],” to provide a comprehensive criticism of Dühring (31).

Concerning their friend Lange, he argued in 1865 that the “Hegelian system [was] a step backward towards scholasticism,” and that Hegel’s views on mathematics and natural science were a substantial “weak spot” (47). In the same year Engels sent him a letter defending “the titanic old fellow” and argued that Hegel’s “true philosophy of nature is to be found in the second part of the ‘Logic,’ in the theory of essence, the authentic core of the whole doctrine” (ibid). To this he added that the “modern scientific doctrine of reciprocity of natural forces [was] just another expression or rather the positive proof of the Hegelian development on cause & effect, reciprocity, force, etc.” (ibid). Kangal notes that Lange’s latter work shows he took “Engels’ comments on Hegel seriously,” to the point of having developed in the posthumously published Logical Studies a “dialectical theory of probability” (48).In addition to the debates during the lifetime of Marx and Engels, Kangal also covers the debates that took place in the interlude between Engels’ death and the Russian 1917 revolution. For instance, he presents the arguments of the Russian Khaim Zhitlovskii (1896), who was the first to attempt a divide between Marx and Engels on the subject of natural dialectics; the arguments from the German revisionist Edward Bernstein (1921), who argued that “the great things which Marx and Engels achieved, they accomplished in spite of, not because of, Hegel’s dialectics”; the critical reply from the Austrian Marxist philosopher Karl Kautsky (1899), who in seeing and affinity between Bernstein and Dühring rhetorically asked (quoting Engels), “what remains of Marxism if it is deprived of dialectics that was its best ‘working tool’ and its ‘sharpest weapon?’”; and lastly, the debates between Austrian-Marxist Max Adler (1908) and the Russian Marxist Georgii Plekhanov (1891) over the former’s attack, and the latter’s defense, of philosophical materialism and dialectics (49-52).Kangal also provides a thorough study of the debates and contradictions that arose in the Soviet Union concerning the relationship of Marxism to Hegel, Marxism to philosophy, and of dialectics to nature. Focusing on the debates between the Deborinites and the Mechanists, Kangal brilliantly shows the plurality and heterogeneity of Marxist thought that existed in the Soviet Union. He says, “it is no exaggeration to say that the Soviet debates accumulated an astonishing variety of contradictions, even if some figures embodying those ambiguities, or later historians narrating them, would not openly admit this” (60).In journals like Pod Znamenem Marksizma (“Under the Banner of Marxism”), Vestnik Kommunisticheskii Akademii(“Bulletin of the Communist Academy”), Bolshevik, and Dialektika v Prirode (“Dialectics in Nature”) these debates would openly take place between scholars and party theoreticians (ibid). The research Kangal does of these Soviet debates lucidly depicts the monumental ignorance of ‘western’ Marxists’ dogmatic critiques of what they labeled as ‘Soviet Marxism.’ Such homogeneity never existed, plurality and debate were always present. Only in the anti-communist plagued minds of western Marxists did such homogeneity exist in Soviet philosophy.

One of the novel points Kangal stresses is that the “197 manuscript fragments” contained in the “four folders” that would be made into the book we now know as Dialectics of Nature (or Dialectics and Nature for the 1927 German edition), has its “completeness and maturity… editorially imposed” (58, 3). This is something that has been mostly ignored by both sides of the Engels debate, each which assumed that, although incomplete, the book had a single and consistent intention it aimed to carry out. In response to this historical misreading of Engels’ intentions, Kangal states that,

There is not necessarily a single overriding intention, a single goal, and a single argument in his entire undertaking; Engels’ readers do not appear to be prepared to accept the fact that some of his intentions, articulated or otherwise, might be incomplete, or incongruent with his other intentions, goals and arguments (184).

Considering the former, Kangal argues that Engels’ “work in progress… remained incomplete” (124-5). This “incompleteness theorem,” as Kangal names it, states that “it is by no means self-evident that Engels’ project was ‘not finished’” (125). As he notes, a work can be “completed without being published” (ibid). A good example of this is The German Ideology, which although left to the “gnawing criticism of the mice,” nonetheless completed its “main purpose – self-clarification.”[5]One must ask, then, – why did Engels embark on such a momentous project? After providing a magnificent Marxist analysis of the function of theory and its relationship to practice, of the role of intellectuals in the workers’ struggle for socialism, and of the role of philosophy in relation to theory and practice, Kangal postulates four main motives behind Engels’ project: 1) “the political goal was to win over all (potentially) progressive forces, including natural scientists, to the socialist cause”; 2) to provide the natural sciences – who although think themselves to be free of philosophy are actually, according to Engels, always “under the dominion of philosophy” – the “methodological indispensability of philosophical dialectics”; 3) to consciously incorporate into the theoretical sciences the only method capable of comprehensively understanding the results derived from scientific studies – the Marxist materialist dialectics; and 4) to move beyond Ludwig Feuerbach’s insufficient discarding of Hegel, and instead sublate Hegel by showing that his revolutionary method is confirmed in nature and its historical development (something which Hegel rejected) (111-13).

In addition, after Marx’s death, Engels realized that Marx had never written the “2 or 3 sheets” he promised to him and Joseph Dietzgen where “the rational aspect” of Hegel’s method would be made “accessible to the common reader” (108). This, argued Kangal, was also an “occasion” (instead of a “direct reason”) for Engels’ undertaking in Dialectics of Nature (110).

After covering the Engels debate both contextually and genealogically, and providing a textual history of Dialectics of Nature and the multiple purposes behind it, Kangal dives into the most philosophically dense part of the book – his critical assessment of dialectics in Engels’ text. It is important to remember that although the critiques are directed at Engels and his Dialectics of Nature, the flaws Kangal points to are in Marx as well, for their perspectives on these were waged jointly. Here are some of the most important critiques Kangal provides of Engels’ “philosophical ambiguities” (125).

1- There are quite a few ambiguities and loose ends with Engels (and Marx’s) treatment of Hegel. First, Engels incorporates Hegelian categories (primarily from the first two sections of Hegel’s Science of Logic and Shorter Logic – the “Logic of Being” and the “Logic of Essence”) without an explanation for the differences in order and prioritization in how they appear in his and Hegel’s work. In Engels’ treatment, for instance, the categories from Hegel’s chapter “The Essentialities or Determinations of Reflection” (quantity/quality, identity/difference and its development into the categories of opposition and contradiction), are conjoined with the category of sublation (aufhebung) which Hegel introduces at the beginning of the “Logic of Being”, and are raised to the status of being ‘dialectical laws,’ that is, “the most general laws” of the “history of nature and human society.” These are, of course, the famous three – the “law of the transformation of quantity into quality and vice versa, the law of the interpenetration of opposites, [and] the law of the negation of the negation.”[6]

Why he chooses these to be ‘laws’ over other Hegelian categories he uses throughout his work (like force/manifestation, coincidence/necessity, causality/reciprocity, shine/essence, nodal line, etc.) is unclear. Similarly, why some of Hegel’s categories are fully discarded with is also left unexamined. In addition, the treatment of Hegel’s Logic (which he primarily uses the Shorter Logic for) contains no consideration for Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, which Hegel argued his Science of Logic was the “first sequel” of.[7] With the exception of his critiques of Hegel’s philosophy of nature (which is part two of the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences), Engels leaves what comes before and after the first division of Hegel’s Logic[s] (the sections in Objective Logic) largely unexamined.

The problem here is that it was Engels who, against Feuerbach, argued that Hegel couldn’t just be discarded, that his philosophy had to be “sublated in its own terms” (113). By discarding such a large amount of Hegel’s work, and further, by leaving largely unexplained the reasons for using those parts of Hegel which he does, Engels replicates (in a more advanced form) the Feuerbachian discarding of Hegel and fails to fully meet his own standards.

2- There are two central bifurcations Engels is engaging with in this text: dialectics and metaphysics, and idealism and materialism. As every Marxists knows, dialectics and materialism are supposed to be the ‘good guys’ and metaphysics and idealism the ‘bad guys.’ However, as Kangal shows, what allows for this neat separation is a synecdochal understanding of idealism and metaphysics on the part of Engels. Contrary to the common Marxist understanding, Kangal shows that there is a “compatibility rather than divergence between materialism and ‘a specific sort of) idealism, and between dialectics and (a specific sort of) metaphysics” (6).

Surely, Engels rejects Hegel’s depiction of the “realization of Spirit” or the “externalization of the Idea” by postulating the “primacy of nature over logic.” But this ‘inversion’ of what Hegel calls in his Philosophy of History a “true Theodicy” is not in itself a rejection of idealism en toto, but of a specific aspect of a particular philosopher’s (Hegel) objective idealism.[8] As Kangal states,

Hegel and Engels diverge in the following respect: materialism regards nature as a self-grounded totality with its own history, while this is denied by idealism. Idealism presupposes a ‘Spirit’ that precedes nature into which it ‘externalizes’ itself. Engels has no reason to commit himself to Hegel’s religious mysticism, but this, in turn, is no sufficient reason to discard ‘idealism’ in Hegel’s sense of the term (194).

This wholesale discarding of idealism is shown to be even more absurd by the fact that part of Engels’ critique of the natural sciences, specifically his appeal for a conceptually realist understanding of ‘real infinities,’ is itself an argument for what Hegel would call ‘idealism’ (126). Idealism (in Hegel specifically) argues that,

Singular finite entities have no veritable being without collective dependence and mutual interaction among each other; mutual interdependence of finite parts is an infinitely self-developing totality within which the singular parts play the role of individual moments of the whole (157).

With this Hegelian definition of idealism Engels would be in full accord. The only thing he would disagree with is the characterization of the above mentioned as ‘idealism’. However, “the infinite stands and falls within the area of idealist investigation insofar as it is not subject to finite empirical observations of particular natural sciences” (194). Hence, it would be superfluous to come up with another term for the investigation of the infinite. The term ‘idealism’ is sufficient here.Engels’ unorthodox and synechdochal understanding of idealism (as it appears in the Hegelian tradition at least) is at the core of his (and Marx’s) artificial bifurcation of materialism and idealism. Instead, Kangal argues, we must realize that a “local materialism” and a “global idealism” are perfectly compatible (195). Kangal adds that he “wouldn’t be surprised if it had been a similar conclusion that prompted Lenin’s emphasis on the ‘friendship’ between materialism and idealism” (205).

3- Engels’ treatment of metaphysics suffers from the same setbacks as his treatment of idealism. For instance, in Anti-Dühring he argues that “to the metaphysician, things and their mental images, ideas, are isolated, to be considered one after the other and apart from each other, fixed rigid objects of investigation given once for all.”[9]However, this definition of metaphysics synecdochally depicts what Immanuel Kant and Hegel would call ‘old metaphysics’ as metaphysics en toto. As Kangal notes, “Kant and Hegel famously attack the flaws of ‘old metaphysics’, but Engels takes the anti-dialectics of the old metaphysics to represent the defects of metaphysics as a whole” (195).

RELATED CONTENT: A Critique of Western Marxism’s Purity Fetish

Metaphysics, in the Hegelian tradition specifically, understands that,

Rational foundations of sciences demand a rigorous inquiry into the fundamental structures of reality and our understanding of them; in order to conduct such an inquiry, we need to construct a categorial framework that explicitly formulates and self-critically revises the conceptual tools in use in order to improve our command of the ways we experience and think of the world (157).

Once again, Engels’ text is littered with examples which depict his agreement with the above-mentioned propositions. The only disagreement here is terminological, that is, Engels would only reject the term metaphysics being used to describe the former perspective. This rejection, however, is grounded on his stinted understanding of metaphysics qua old metaphysics. There is, then, no contradiction at all between dialectics and metaphysics as described above. In fact, as Kangal rightly states, “Engels’ defense of philosophy against positivism is a defense of ‘metaphysics’’’ understood in these terms (195). For Hegel – who Engels and Marx praise and consider as the point of departure for Marxist materialism – one cannot escape metaphysics, human beings are “born metaphysicians”; all that matters is “whether the metaphysics one applies is of the right kind” (161).[10]

Kangal’s text also explores how the ambiguities present in Engels’ understanding of the relationship of idealism and materialism, and metaphysics and dialectics, are reflected and refracted into further confusions and knots concerning his association with Aristotle and his disassociation and critique of Kant. His text additionally traverses how these ambiguities are intensified by the variances between Engels’ Plan 1878, Plan 1880, and his four folders for Dialectics of Nature (165-176).

It is impossible to do justice, in such limited space, to such a wonderful work of Marxist scholarship. What I can say is this, any reader of Kangal’s book will surely appreciate its abundance of letter references and its resuscitation of texts which have been largely obscured in anglophone Marxist scholarship over the last half a century. Even in the most philosophically muddy places of Kangal’s text, he does an exceptional job at clarifying things for the reader. In contrast to what a recent critical reviewer of Kangal’s text argued, the difficulties found in the philosophically densest section of the text are not the fault of Kangal, but of Engels (and Marx, who shares Engels’ flaws), who uses unorthodox and synechdochal definitions of idealism and materialism, and dialectics and metaphysics, to position himself in relation to Aristotle, Kant, and Hegel. If anything, Kangal must be thanked for untangling, in his comparative and critical analysis of the aforementioned thinkers, knots set by Marx and Engels’ philosophically unorthodox usage of the previous concepts.

Notes

[1] Two essays withing the Dialectics of Nature manuscript collection had already been published before by Eduard Bernstein, “The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man” (1895/6) and “Natural Science in the Spirit World” (1898).

[2] All numbers cited in the review article come from Kangal’s text: Kaan Kangal (2020), Friedrich Engels and the Dialectics of Nature, Palgrave.

[3] Edmund Husserl (1913), Ideas I, Hackett (2014)., pp. 109.

[4] Paul Blackledge article for Monthly Review (May 2020) “Engels vs. Marx?: Two Hundred Years of Frederick Engels,” also does a splendid job at countering the ‘betrayal’ or ‘corruption’ thesis of the Marx-Engels bifurcators.

[5] Karl Marx (1859), A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, International Publishers (1999)., pp. 22.

[6] Friedrich Engels (1964), Dialectics of Nature, Wellred Books (2012)., pp. 63.

[7] G. W. F. Hegel (1812), The Science of Logic, Cambridge (2015)., pp. 11.

[8] G. W. F. Hegel (1837), The Philosophy of History, Dover Publications (1956) ., pp. 457.

[9] Friedrich Engels (1879), Anti-Dühring, Foreign Language Press (1976)., pp. 20.

[10] It is also important to note that this ‘throw the baby out with the bathwater’ approach taken to idealism and metaphysics was never applied to the flaws they both saw in various parts of the materialist and dialectical tradition.

Featured image: Kaan Kangal, Friedrich Engels and the Dialectics of Nature (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 213 pages.

Carlos L. Garrido is a Cuban American philosophy instructor at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. He is the director of the Midwestern Marx Institute and the author of The Purity Fetish and the Crisis of Western Marxism (2023), Marxism and the Dialectical Materialist Worldview (2022), and the forthcoming Hegel, Marxism, and Dialectics (2024). He has written for dozens of scholarly and popular publications around the world and runs various live-broadcast shows for the Midwestern Marx Institute YouTube. You can subscribe to his Philosophy in Crisis Substack HERE.