‘Four Meals from Anarchy’: Rising Food Prices Could Spark Famine, War, and Revolution in 2022

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

By Alan MacLeod – Dec 17, 2021

The political consequences of hunger are profound and unpredictable but could be the spark that lights a powder keg of anger and resentment that would make the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests look tame by comparison.

Already dealing with the economic fallout from a protracted pandemic, the rapidly rising prices of food and other key commodities have many fearing that unprecedented political and social instability could be just around the corner next year.

With the clock ticking on student loan and rent debts, the price of a standard cart of food has jumped 6.4% in the past 12 months, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, with the cost of eating out in a restaurant similarly spiking, by 5.8% since November 2020.

The most notable change has been in the price of meat, with beef costing 26.2% more than it did last year, pork 19.2% more and chicken 14.8% more. Bacon prices have reached historic levels, and are now 36% higher than in 1980, even after adjusting for inflation. And with new animal welfare laws coming into effect soon regarding the minimum space required for pigs, some have predicted widespread shortages of bacon and a further price increase of up to 60%.

Eggs, sugar, and fresh fruit and vegetables have also hit consumers’ wallets, putting the average cost of hosting a Thanksgiving dinner at $53.31 this year, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation’s annual survey. This is up from $46.90 in 2020—a 14% increase and the most expensive it has ever been since the organization began tracking costs in 1985.

Facing unprecedented rises in costs, McDonalds announced that its prices were increasing by around 6%, while Dollar Tree has taken the decision to ditch its branding of over 30 years and roll out a 25% price increase on many of its products, meaning they will cost $1.25.

An unmerry Christmas

Food price rises are merely one aspect of a worrying overall trend, which has seen the consumer price index—a general measure of how much it costs to live an ordinary life in the US—increase by 6.8%, the largest year-on-year spike since 1982. Gasoline costs 58% more than it did last year, while gas heating has increased by over 25% and home electricity costs by 6.8%.

Rising costs disproportionately impact working-class Americans. The poorest fifth of households spend far more of their income on food and groceries than the richest fifth, according to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA). 42 million Americans rely on the SNAP program to buy food. Seeing the urgency required, the USDA increased monthly payments in October by an average of $36.

Still, the majority of Americans are already flat broke. Nearly two-thirds of the country currently lives paycheck to paycheck, and just 39% of Americans believe that they could cover a $1,000 emergency. Thus, with rising heating, transport and food costs, Christmas is likely to be particularly lean this year for hundreds of millions of people.

Before the pandemic, one in eight Americans, including one in six children, regularly went hungry. Some 30 million children rely on schools for meals, but with COVID-related closures, that source of nourishment has sporadically been lost. Facing this pressure, many Americans simply have not been able to cope. Feeding America, the nation’s largest chain of food banks, told MintPress that they have been forced to purchase 58% more food than last year to meet ever-rising demand. Katie Fitzgerald, the company’s president and COO, stated, “There are more than 38 million people, including nearly 12 million children, facing hunger in the US. Our food banks and partners are resilient and are doing everything they can to continue to provide food to our neighbors in need, but we cannot sustain this level of response without the continued support from the public and private sector.”

The effects have been felt across the country, but not equally. Save The Children identifies East Carroll Parish, Louisiana as the county with the highest food insecurity rate in the nation. In the far northeast of Louisiana, among the bayous and fields just west of the Mississippi River, 40% of children do not get enough food to eat; a rate comparable with Bangladesh and Peru, and higher than in sub-Saharan nations such as Mali. Those on the front lines against hunger told MintPress that rising prices have dramatically affected the amount of groceries they could purchase and distribute. Jen Toth, Executive Director of the Food Bank of Northeast Louisiana, noted, “The higher cost of food has definitely been felt by those living on very low fixed incomes or low hourly wages. Their dollars simply don’t stretch as far, and they aren’t able to buy the same amount of food compared to a year ago. Unlike rent and utilities, food is one expense that a person can control, but unfortunately that can mean in order to be able to pay other bills, a senior or a family won’t have enough money left to buy food.”

A bread-and-butter wave?

The political consequences of hunger are profound and unpredictable but could be the spark that lights a powder keg of anger and resentment that would make the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests look tame by comparison. President Joe Biden’s approval ratings are sinking, with some polls showing he is backed by only 39% of Americans. Even fewer—31%—think the country is on the right track. Already, Republicans appear to be making the greatly increased cost of food and gasoline a major focus of their attacks against the 46th president. The hashtag #ThanksgivingTax trended on social media last month, as conservatives pinned the blame for the costly festivities on their political opponents.

All 435 seats in the House of Representatives, 34 Senate seats, and many governorships and state legislative majorities will be decided in the 2022 midterm elections. Preliminary polling suggests a huge red wave of anger sweeping across the United States. As CNN recently wrote, “Pretty much every single indicator that pointed to a Democratic wave in the 2018 midterms now points to a Republican one in the 2022 midterms.”

Biden has backtracked on debt cancellation promises, while the Democrats, stymied by the stubborn recalcitrance of Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV), appear to have shelved the Build Back Better agenda until at least the new year. Build Back Better includes a great deal of poverty relief that food banks and other charities have been imploring the government to pass. While the general public often pays little attention to political scandals on the hill, food and gas prices are things that tangibly affect every one of us. These bread-and-butter issues could translate into a wave of public resentment and a slump in support among the Democrats’ voter base.

However, an electoral defeat turning him into a lame duck president might be the least of Biden’s woes. Around the world, rising food prices pushing people to the brink have frequently been the catalyst for mass actions, rebellions and revolutions.

Marion Nestle, professor emerita at New York University and author of the seminal work “Food Politics,” warned, “Rising food prices are not popular and [are] viewed as a sign of poor government. They are already having political consequences in that they are viewed as a criticism of Biden administration policies, whether or not those policies are actually responsible. Hungry people, harking back to Shakespeare, are dangerous. Hunger induces desperation.”

Nestle suggested that the political ramifications of rising prices depend upon how desperate people become. “I don’t have a crystal ball. If people can’t afford to feed their families, and the shortfalls are not made up by food assistance policies, it’s hard to predict what will happen,” she observed. “But it seems to me that a basic function of government is to ensure the welfare of its citizens and that means food, among other necessities.”

Food corps bring home the bacon

Facing increased criticism, the Biden administration has placed the blame for inflated prices on “the greed of the meat conglomerates.” “When people go to the grocery store and they’re trying to buy a pound of meat, two pounds of meat, ten pounds of meat, the prices are higher,” said White House Spokesperson Jen Psaki recently. “You could call it corporate greed, sure,” she added.

While Republicans have cast this off as shifting responsibility, there is certainly some truth to Psaki’s claims. While working-class Americans have been feeling the strain, food giants have been reveling in profits. The share price of Tyson Foods (the country’s largest processor and marketer of chicken, beef and pork) has moved from $63.05 last Christmas to $86.63 today—a 37% jump. Meanwhile, PepsiCo stock has risen from $145.06 to $171.82 and Nestlé’s from $109.56 to $137.13 over the same period. (Marion Nestle is not related to the food conglomerate).

Also to blame is a worldwide shortage of nitrogen fertilizer, meaning that prices are at least 80% higher than last year. Farmers held off purchasing it in the hopes that costs would drop, but instead were left with the options of paying the greatly increased price or going without and accepting far worse crop yields for 2021—both of which translate into higher prices for the consumer.

The hot and dry summer of 2021, which caused fires across the western part of the continent and parched fields across the midwest, is also a serious factor. The USDA recently announced that the 2021 wheat harvest was America’s worst in 20 years. The record temperatures also destroyed Canada’s agricultural output, with wheat production dropping by 35% and canola by 24%. Higher fuel prices also greatly affected the agricultural sector.

These costs have been passed down to stores, food banks, and, ultimately, the consumer. “Supply chain disruptions, lower inventories at the retail and manufacturer level, costs for fuel, transportation and labor shortages, along with other disruptions, are affecting food banks throughout the country. Freight costs to move donated food have increased over 20%,” Fitzgerald said.

There is little good news on the horizon, as food prices are set to rise again in the near future. The USDA predicts at-home expenses will increase by 1.5% to 2.5% and restaurant prices by between 3% and 4%. It should be noted, however, that the USDA underestimated the 2021 rise considerably.

A global powder keg

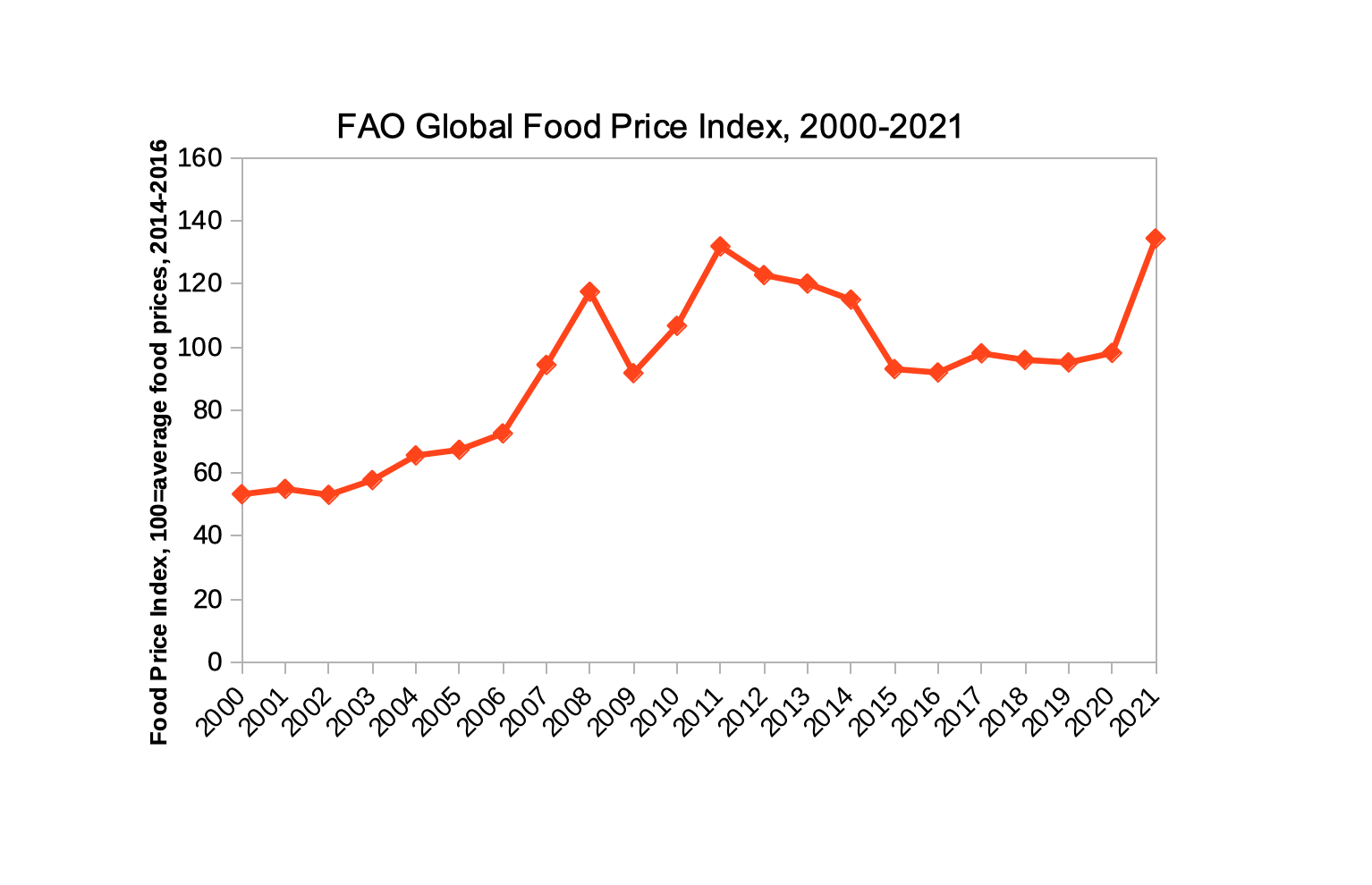

If the situation is bad in the United States, it is perilous around the globe. Fully 811 million people, around one tenth of the world’s population, already regularly go hungry, according to the United Nations. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization notes that food prices globally are as high as they have been in living memory, with the cost of nourishment spiking by 37% in the past 12 months.

Much of the world is at risk of famine. The UN is warning that 28 million people in western and central Africa are at risk of starvation if nothing is done. Madagascar is also facing its worst drought in 40 years, and is in need of urgent food aid. Yet with the pandemic interfering with both harvests and global supply lines, this is no easy task.

RELATED CONTENT: How Washington led the Purge of Christians from its ‘New Middle East’- Part 1

Meanwhile, Lebanon is facing a range of crises, from an economic collapse to the massive destruction in Beirut caused by the 2020 port explosion. Currency depreciation has seen the Lebanese pound lose 90% of its value and food prices increase by 628% in the previous two years. Across the border in Syria, 12.4 million people—more than half the population—are struggling to find food. Since 2000, the Arab world has witnessed a 91% increase in hunger, to the point where one-third of the region does not get enough food, according to a new UN report. The World Food Program has estimated it needs to find nearly half a billion dollars by February to avert a humanitarian catastrophe.The best predictor of political instability—be it wars, coups, revolutions or revolts—is not GDP or unemployment; it is the price of staple foods. “If I were to pick a single indicator—economic, political, social—that I think will tell us more than any other, it would be the price of grain,” said Lester Brown of the Earth Policy Institute.

Few remember it today, but 11 years ago, the Arab Spring was sparked by rising food insecurity. Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian fruit and vegetable vendor, set himself on fire in the town of Sidi Bouzid, protesting the government of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. This prompted a wave of public anger, fueled by empty stomachs. By January, 2011, the country was ablaze with revolution. Ben Ali well understood what was driving the revolt, and announced the price of basic foodstuffs would be lowered. However, it was too little, too late, and he was soon forced to flee to Saudi Arabia.

The protest quickly spread to Egypt, which had seen food prices double between 2007 and 2011. Under President Gamel Abdel Nasser (1956-1970), Egypt had been the world’s largest wheat exporter. However, then-President Mubarak embraced neoliberal globalization, allowing the country to be flooded with subsidized American grain, which caused a crash in the agricultural sector to the point where the country became the planet’s top importer of wheat. This new food insecurity was the major driver of popular anger, with Mubarak being forced out to chants of “bread, freedom and social justice,” a phrase that became the slogan of the movement. Egyptians famously attached loaves to their heads to make “bread helmets”—a symbolic gesture showing the world what the protest was about. Rising food prices also played a major factor in protests in Syria and across the Middle East.

Going further back, the Russian Revolution, one of the most momentous events of the 20th century, began as a Women’s Day protest against bread shortages. However, things soon escalated, as hundreds of thousands in St. Petersburg came out to show their anger. Barely a week later, Czar Nicholas II abdicated. This took political leaders completely by surprise. As late as January 1917, Vladimir Lenin gave a speech to other political exiles in Switzerland, where he claimed that their generation would never see revolution in their lifetimes. Only a few months later, he would become the head of state.

The short-lived provisional government that took power after the czar’s fall enjoyed widespread support at first. Yet their steadfast failure to improve the desperate situation in Russia led to their demise. By the time the provisional government fell, the crisis was so profound that cannibalism was rife in the Russian capital of St. Petersburg. With the slogan “peace, land and bread,” Lenin and the Bolsheviks rose to power and changed history forever.

The current spike in global food prices is sharper than it was in 2011. Today, food is even more expensive than it was at the beginning of the Arab Spring, and most signs point towards continued increases in 2022.

The British government has historically maintained that the United Kingdom is only ever “four meals from anarchy”—meaning that the country would descend into widespread disorder, rioting and protest if stores were to run out of food for more than a day. While there is little to no indication of that happening in the US, hunger is on the rise, and with it political disenchantment. What form that will take remains to be seen. Globally, however, the situation is as grave as it has been in living memory, and it seems inconceivable that there will be no political ramifications to the shortages. If so, it could make the Arab Spring look mild by comparison.

Featured image: A protester holds bread during a demonstration in Tunis, January 26, 2021. Photo: Hedi Ayari / AP

Alan MacLeod is a member of the Glasgow University Media Group and a Senior Staff Writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent, as well as a number of academic articles. He has also contributed to FAIR.org, The Guardian, Salon, The Grayzone, Jacobin Magazine, and Common Dreams.