By Sonia Fleury – Mar 22, 2022

Her assassination four years ago exposed the hijacking of democracy and the presence of militias in the interior of the State. But Marielle Franco’s life became a seed that inspires the hacking of politics, collective mandates and rebellions in the peripheries of Brazilian society.

It is already four years without her smile, her audacity, her unwavering stance in defense of social justice, the struggle to transform repressive customs and rotten powers through inclusive policies. It is already four years without Marielle, who was brutally murdered on March 14, 2018, along with her driver Anderson Gomes. The fact that until now it is not known who were the main perpetrators for her murder is a powerful reminder of how Brazilian institutions work in favor of individuals and criminal groups who consider themselves untouchable and unimpeachable, corrupting of public agents, distancing them from their functions those whose duty it is to seek the truth in investigations, who instead erase evidence and threaten witnesses.

Guilty silence

This is a glaring case that reveals the existence of networks of assassins and bandits with a peculiar proximity to the dominant political groups in Rio de Janeiro and in Brazil, acting clandestinely in official institutions. These illegal political networks include professional assassins such as former congressman Ronnie Lessa, recognized as a killer, active in the war of the bicheiros [illegal gambling and casino mafia], who, despite his modest income, became the president’s neighbor in a condominium on Barra da Tijuca beach. Lessa, who, together with Élcio Vieira Queiroz, was accused of the murder of Marielle, had in his possession an arsenal of 117 rifles.

The illegal network also includes members of gangs linked to international trafficking and theft of weapons from the police and armed forces, militiamen such as former BOPE (Special Police Operations Battalion) captain Adriano Nóbrega, leader of the Crime Bureau; and practitioners of extortion, land grabbing and homicides. While in prison, Adriano received the Tiradentes Medal, the highest honor of the Legislative Assembly of Rio de Janeiro, from the hands of Congressman Flávio Bolsonaro, who also hired members of Adriano’s family as parliamentary advisors. Adriano ended up assassinated in 2020, after expressing his fear of being the victim of a “burning of files.”

RELATED CONTENT: Argentina: Hunger and the Capitulation of the Political Class

So many years have passed and despite the fact that at the time of Marielle’s murder, Rio de Janeiro was under military intervention, commanded by Army General Walter Braga Neto—currently Minister of Defense—to this day there are no answers to many questions raised by the Marielle Franco Institute. These include: manipulation of evidence in the car in which Marielle was traveling at the time of her murder, lack of coordination between state and federal bodies, failure of Google to send the data requested by the MPRJ (Rio de Janeiro Public Ministry) and the Civil Police, numerous changes of command in the Homicide Police Station responsible for the case, fraud attempts, change of the superintendent of the Federal Police investigating interference in the investigation, alteration of the testimony of the doorman of the condominium where Jair Bolsonaro and Ronnie Lessa (one of the murderers) lived.

The guilty silence is accompanied by actions that perpetrate violence both symbolically, such as the breaking of the plaque paying homage to Marielle by federal deputy Daniel Silveira (PSL-Rio de Janeiro), who was arrested for attacks on the Supreme Federal Court and had been supported as a possible candidate for the Senate by the Bolsonaro family; and through the extermination and repression of young black people in the favelas, who Marielle represented. In 2021 alone, the Military Police killed 109 more people in Rio de Janeiro than in 2020.

The symbol

One has to wonder what led thousands of people, mostly young people, to take to the streets to mourn the murdered councilor, in a scene that has been repeated in several cities, countries and dates since the murder, chanting slogans like “Marielle is present, she has become a seed!”

Marielle was elected councilwoman of Rio de Janeiro in 2016, aged 37, with 46,502 votes, being the fifth most voted parliamentarian in these elections. Introducing herself as a woman, Black, mother, sociologist, native of the favela of Maré, defender of human rights and LGBTQIA+ population, Marielle synthesized a personal and collective trajectory of struggles and achievements of the population of the favelas and the peripheries and of identity movements.

Having become a mother at the age of 19, she was part of the statistics of teenage pregnancies in the favelas, which interrupted her studies, and she returned afterwards to study at the community pre-university of the Centro de Ações Solidárias da Maré (CEASM). She entered the Social Sciences degree program at the Pontifical Catholic University PUC/Rio de Janeiro in 2002, obtaining a full scholarship from the University Program for All (Prouni). Marielle’s dissertation in 2014 exposed “a policy aimed at repression and control of the poor from the discourse of social insecurity, the most important mark of this framework being the militaristic siege in the favelas and the growing process of incarceration, in its broadest sense.”

RELATED CONTENT: Brazilian Precandidate Sergio Moro’s Accounts Frozen Due to Bribery Charges

Marielle was an inspiration of thousands of young people trapped in the favela’s to get an education. The entry of young people from the favela and the periphery into universities is the result of the insurgence of youth against the place of exclusion that society assigns them, in an environment of individualism and competitiveness, in which the promises of success through entrepreneurship end up blaming those who fail to achieve it. In the face of the hegemony of neoliberal values, it is important to recognize the emergence and proliferation of Cultural Collectives that challenge the norm by their very existence.

Since 2019, the majority of students in federal universities are black and come from public schools. In addition to allowing greater social mobility with the entry of people with lower income levels, it has provided engagement with higher education, with efforts of groups such as Educafro to overcome the exclusion of young blacks by the denial of access to quality education.

Marielle became a symbol of the identity struggles of women, blacks, LGBTQIA+ population, which today touch the hearts and minds of young people of all social strata. Far from the simplistic view, which considers identity struggles as a false consciousness that fractures the class struggle, Marielle’s performance as a parliamentarian and human rights activist with social movements always linked the different forms of exploitation to the reproduction of domination and social exclusion.

The seed

Marielle’s campaign slogan, “I am because we are,” inspired by the African concept Ubuntu, announced her candidacy as a collective construction that materialized in the Marielle Franco Mandates. Mandates are a new way of composing an office, through a collective mandate, fruit of the growing popular participation in the struggle for democratic representation. If before, social and identity movements were predominantly focused on the mobilization and organization of collective actions of vindication and denunciation, recently the occupation of legislative assemblies by popular representatives and/or groups discriminated against and excluded from the spheres of power has proliferated in the country.

Mandates are an innovation in the exercise of representation, fruit of the collectivist experience in popular struggles and social movements. Although the electoral legislation only allows the presentation of one candidacy, the device created by the mandate allows the joint exercise of representation. This is the first “foot in the door,” an expression often used by Marielle, in the exercise of politics as representation. The proliferation of mandates shows that this is an innovation that is here to stay.

In the first elections which followed Marielle’s murder, three black women from Marielle’s mandate were elected as state deputies for PSOL Party in Rio de Janeiro: Dani Monteiro, Renata Souza and Monica Francisco. In addition, Erica Maluginho, from PSOL, was elected to the ALESP [legislative assembly of São Paulo], and Benny Briolly to the Municipal Council of Niterói, the first black and trans women in the Chamber. In Joinville, the first black councilwoman to be elected was PT’s [Workers’ Party] Ana Lúcia Martins. PSOL also elected federal deputies Taliria Petrone for Rio de Janeiro and Áurea Carolina for Minas Gerais. These are the seeds that have borne fruit and have increased the participation of black women in political representation as never before. Yet, these parliamentarians are constantly subjected to racist, homophobic and transphobic attacks, symbolic violence and death threats, demonstrating how far we are from the democratization of political power in a society where racism, patriarchy and homophobia structure class domination.

Sonia Fleury is a senior researcher at the Center for Strategic Studies (CEE) of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation. Coordinator of the Diccionario de Favelas Marielle Franco do ICICT/FIOCRUZ.

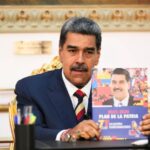

Featured image: Poster showing murdered Brazilian politician and activist Marielle Franco’s face in a background of flowers. Photo: Elástica magazine

(Resumen Latinoamericano – English)