Human Rights Conditions Have Deteriorated Rapidly Under Bolivia’s De Facto Government

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

By Lola Allen and Brett Heinz – March 24, 2020

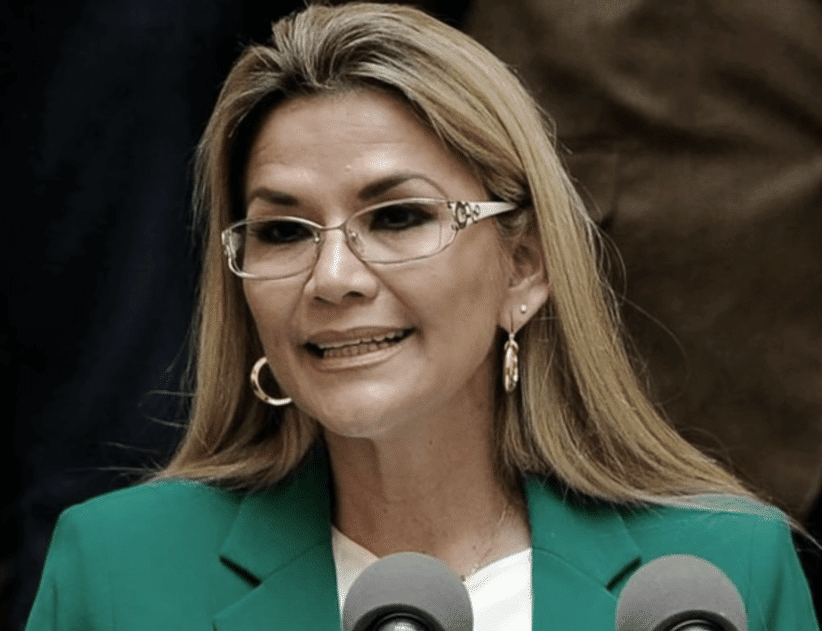

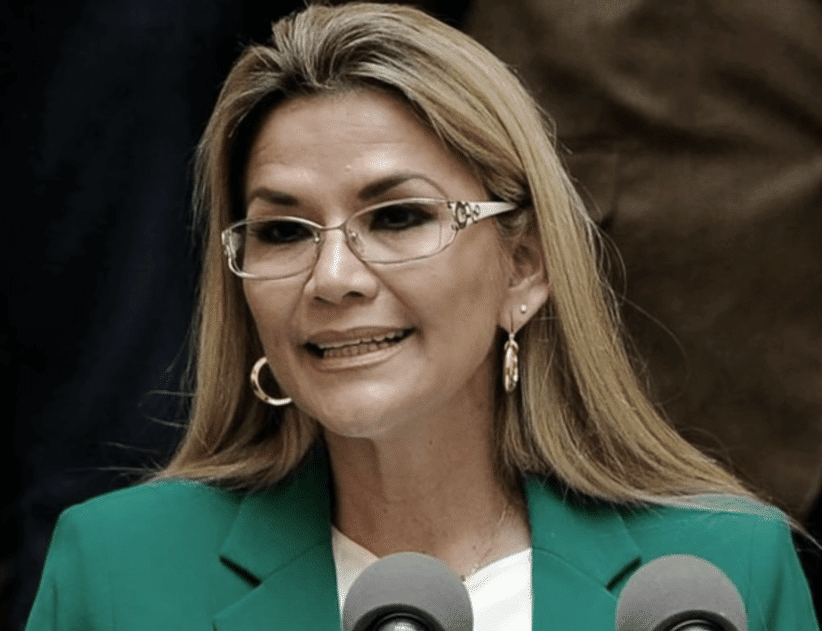

Since the de facto government of Jeanine Áñez took power in early November 2019, the human rights situation in Bolivia has significantly deteriorated. Various government actions have been strongly criticized by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the Organization of American States (OAS), and over 850 public figures and scholars. Earlier this month, Bolivia’s human rights ombudsman — an independent government official appointed by the legislature — called for an “urgent visit” by UN experts to report on “violations of human rights,” and requested the same from the IACHR.

The following is a summary, not comprehensive, of various human rights violations under Bolivia’s de facto government:

Police Violence — Repression by security forces and paramilitary organizations resulted in 35 dead, 833 injured, and 1,504 arrested by late 2019. The OHCHR reported 600 detentions in a single period lasting less than four weeks. Bolivia’s Torture Prevention Service reported violence and abuse against the newly arrested, but the head of that agency has since resigned, allegedly having been asked to do so. In November, the government passed Decree 4078 to provide legal immunity to security forces involved in abuses (a move met with harsh condemnation by Amnesty International) and only repealed it after multiple police massacres of protestors had taken place. Government officials have repeatedly skipped congressional hearings on the massacres. When the families of the deceased publicly protested, they were met with a police tear gas attack so severe that a nearby school had to be evacuated, with 100 children affected. The government has also stepped up its attempt to militarize social conflict by creating new “anti-terror” security forces, enlisting the military to participate in domestic law enforcement, and introducing new measures to make military and police spending confidential.

RELATED CONTENT: Bolivia on the Verge of a Social Explosion Against the Pandemic and the Government

Paramilitary Violence — Extralegal violence has been widespread: officials in the MAS party and their supporters have had their houses burnt down, their family members kidnapped, and have been repeatedly beaten in public. Not only has law enforcement failed to open investigations into most of these attacks, but IACHR reports indicate that violent militias have “acted in association with state law enforcement” or have been “tolerated” by them. The police have failed to address this, leading Bolivia’s human rights ombudsman to raise concerns about the issue.

Assault on MAS and Former Government Officials — As the de facto president goes back on her earlier commitment not to run in the upcoming elections, she is engaging in far-reaching persecution of her main electoral opponents. Former MAS officials have been prosecuted on dubious charges including “terrorism” and “sedition,” and many have fled or gone into hiding; 65 local officials resigned due to a “pattern of pressure and intimidation”; 592 former officials have been targeted in an “anti-corruption probe” (to be released before the next election); and election agencies have considered legally revoking MAS’s status as a legitimate political party. Less than 24 hours after it was clear that Luis Arce would be the MAS presidential candidate, the de facto attorney general announced that he was launching a corruption investigation targeting Arce (a local body announced a criminal complaint against David Choquehuanca, the MAS vice presidential candidate, just days before). Former president Evo Morales has been charged with terrorism, forced to flee the country, been legally barred from running as a senate candidate in the upcoming election, and had his lawyer arrested in an act that was condemned by the human rights ombudsman.

Freedom of the Press — Bolivia’s de facto communications minister has threatened journalists whom she has accused of “sedition,” claiming within weeks of taking office that she already had a list of journalists in mind (sedition charges are now widely abused: Bolivia’s human rights ombudsman has noted that while there have been 22 charges of sedition in the last four months, last year saw only two). Journalists and presidents of private news organizations have been arrested, and 53 community radio stations have shut down. At least 50 journalists were assaulted in late 2019 (including the deliberate teargassing of a TV reporter on camera), and certain news channels have been censored. One Argentine journalist was beaten to death in unknown circumstances.

RELATED CONTENT: Bolivia: People Break Quarantine to Protest for Lack of Food

Freedom of Speech — Students and state employees have been arrested for social network posts critical of the government, a move which even some opponents of Evo Morales’s MAS party have labeled “totalitarian.” Some activists have alleged that the de facto government has been removing communications antennas in rural areas in order to hamper cell service where opposition to the government is strongest.

Racism — Threats and harassment have been particularly focused on indigenous communities and the secular nature of the Bolivian state. Upon taking power, Áñez stated that “God has allowed the Bible to re-enter the Palace.” She has made multiple racist Tweets about indigenous Bolivians, including calling them “satanic.” In December, the OAS passed a resolution condemning “the human rights violations and the use of violence against any citizen of Bolivia, especially any and all forms of violence and intimidation against Bolivians of indigenous origin.” This did not prevent Áñez from later speaking of preventing “the savages” from returning to power.

Rule of Law — The de facto government has drastically exceeded its stated mandate as a “caretaker” government overseeing the implementation of new elections by making substantive changes to Bolivian foreign policy, agriculture, criminal justice, and more. The government has also ignored Article 158 of the Bolivian Constitution by maintaining a defense minister in place even after he had been censured by the Legislative Assembly.

International Relations — United States Rep. Hank Johnson and 13 other members of congress signed a letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in November 2019, raising concerns about “an escalating political and human rights crisis.” When the IACHR attempted to create a mechanism to address human rights violations, the Bolivian government vetoed the appointment of two of its members in a move condemned by 40 human rights groups and US House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Eliot Engel. Three Spanish and Mexican diplomats were expelled following a diplomatic crisis during which Spain accused the Bolivian government of harassing its diplomats and violating the Vienna Convention. When the Mexican air force sent a plane to provide Morales with asylum, Bolivian authorities and their regional allies repeatedly attempted to block them in a “tense” standoff where “a serious situation could easily have unfolded,” according to Mexico’s foreign minister.

With the growing weight of evidence to suggest that the Áñez government has committed widespread human rights violations, major news outlets in the US are only now beginning to publicly question the role that the US government has played in supporting the de facto government.