Yemeni girl with an atribulated look shows her face will covering behind a metal object, Yemeni mountains in the background. Photo: Kellie Ryan/IRC.

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

Yemeni girl with an atribulated look shows her face will covering behind a metal object, Yemeni mountains in the background. Photo: Kellie Ryan/IRC.

In the following interview, Timo Kivimäki analyses the complex, tragic Yemen War, “the worst humanitarian catastrophe in nearly a century” according to the United Nations.

The Finish researcher is an expert in international conflicts. Doctor Kivimäki is the Director of Research, and Professor of International Relations at the University of Bath, UK. His most recent book is titled Protecting the Global Civilian from Violence: UN Discourses and Practices in Fragile States (2021).

Edu Montesanti: How has Yemen gotten to this situation, and how could this catastrophe have been avoided?

Professor Doctor Timo Kivimäki: Yemen’s conflict has plenty of internal reasons that I am not an expert on. In general, my recent research has shown that organized violence – conflicts, authoritarian violence, terror, and chaotic political violence without state involvement – in the Middle East and North Africa [MENA], has its domestic root in the factionalization of the State.

This means that people feel that the State serves only some of the groups of the country, while political elites also use the State for privileging their own ethnic, religious, regional, or other groups. Such factionalism explains almost half of the fatalities of organized violence in the MENA region.

In Yemen, and elsewhere in the MENA region, there is an external reason that explains how conflicts escalate, once often internal reasons have sparked them. This is the fact that external great powers intervene in conflicts militarily, often with a moral declaratory agenda.

Often, great powers come to the defense of weaker parties in conflict and create a situation in which the weaker party has more resources to continue the fight that it will then eventually lose.

In Yemen, Western powers have supported a “government” that does not have enough legitimacy and support to even dare to be present in the country. As a result, its opponents have needed the military support of the dictatorial Saudi Arabian regime that has received some 90 percent of its weapons from the US and about five percent from the UK.

Supporting a weak favorite in a domestic conflict often weakens the State, and makes it unable to offer basic services let alone contain criminal and political violence in the country. In Yemen, State weakening has also been accelerated by the US military operations against terrorist groups, which it launched in early 2008.

When a foreign power wages war in a country without as much as asking the government for permission for each operation, this must humiliate the government which is supposed to offer a monopoly of legitimate violence within its territory.

For the United States, the War on Terror was such an important project that it could not tolerate a government that did not accept the American independent military role inside the territory of the Yemeni people.

At the same time, not many people accept such a role for any foreign power, the right of external power to decide who is to be killed by a drone strike, and thus, there has not been much hope for any Yemeni government to be accepted both by the US and its own people.

As a result “the Yemeni government” has stayed much of the Yemeni war, outside the Yemeni territory, supported by an American ally, Saudi Arabia, unable to create a state that could serve as an instrument of the Yemeni people.

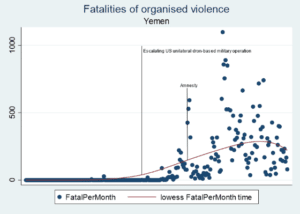

The impact of the US military involvement after March 2008 in Yemen can be clearly seen in the following graph that shows the number of monthly fatalities as dots and a trend curve of escalating violence soon after the US military involvement in the country.

How do you see the presence of foreign military forces in Yemen, engaging billions of dollars in a humanitarian catastrophe? Do you share the view that this is much more of a Saudi-Iran proxy war than any other thing?

I think there are several wars in Yemen, some internal and some external. One of the elements of the external war is power competition between Saudi Arabia and Iran, with the Sunni forces and Shia forces of Yemen.

However, to consider the main war as one between US-supported Saudi Arabia and Iran would probably exaggerate the Iranian role. While Saudi bombings constitute most of the organized violence in the country, the role of the Houthi rebels and especially the support they receive from Iran is much smaller.

This is why I would rather see this war as one in which Saudi Arabia is the main aggressor in a country that has no functioning state.

During the presidential campaign, Joe Biden promised not to support Saudi Arabia in Yemen; soon after taking power, President Biden changed justifying the US support in “defensive weapons” for Saudis”: “Keeping with the president’s commitment to supporting the territorial defense of Saudi Arabia,” said a White House spokesperson.

How do you see Biden’s change, and do you believe such weapons have been used just for defensive purposes?

This is something that puzzles me. During Nixon’s presidency, many of the aggressive inputs in the administration came from the president while the administration then tried to input reason and restraint in policy-making: Nixon for example, ordered a nuclear strike against North Korea, something that the bureaucracy under Kissinger simply ignored for a while until the president had sobered up and calmed down.

During the new millennium, the role of the bureaucracy has had the opposite role. Each of the presidents of the new millennium won their presidency with a campaign that promised to demilitarise US foreign policy: Bush and Trump wanted to focus on America’s own problems and reduce the moralistic interventionism of their predecessors, while Obama and Biden promised to end Guantanamo Bay torture facility and clean up the act of the US military and intelligence apparatus.

Yet, they all ended up increasing the US military effort, with the exception of Trump they all started new wars and backed down from the peace rhetoric they had campaigned with.

Why is this? Some claim it is the power of the capital in the US political system. But surely the huge military expenditure that US foreign policy imposes on corporate taxpayers should discourage 90 percent of the US capital owners from these reckless wars and militaristic adventurism of the US foreign policy.

The military-industrial complex is but a small minority of the US capital owners, the only one that benefits from this tax burden. Yet, it seems that the system forces presidents that get elected based on promises of peace to choose a policy of war.

Can it be that the political system is bought by the arms traders, can corruption, and a relaxed attitude toward “corruptive lobbying,” be the explanation? Frankly, I do not know. Yet it is puzzling why Biden and Trump wanted out of the Yemeni war crimes as they were presidential candidates and yet they fully participated in it after having been elected.

About the solution for the Yemeni tragedy, is “cosmopolitan law enforcement,” a term you approached in your research First Do Not Harm: Do Air Raids Protect Civilians? the right path for it? Please specify a way out of the Yemeni humanitarian catastrophe.

There is a strong popular will against the kind of unilateral, selfish version of cosmopolitan law enforcement, the right that big powers take with might.

Since such unilateralism, as my graph shows, also tends to harm the people it claims to protect, I am sure it should be possible to persuade governments from supporting it. What we need is good data and exposure to the consequences of international efforts by big powers to enact their own interpretations of justice.

We should encourage governments to rely on the UN and UN institutions for the “enforcement of the humanitarian norms”, unilateral powers do not have the justification for it.

Unilateral efforts tend to escalate violence as we have seen in Yemen, while my recent book showed that UN peacekeeping efforts have been exceptionally successful in reducing violence and tackling problems of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Orinoco Tribune special by Edu Montesanti

EM/OT

You must be logged in to post a comment.