Últimas Noticias Survey: Bolívar Continues to Dominate Payment Methods in Venezuela

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

It is quite common to hear that Venezuela has been “dollarized” and that the sovereign currency bolívar is “no longer economically worth anything.” Many of the formal and informal trade prices are set in dollars, although products can be paid and purchased both in bolívars as well as in foreign currencies. The government, however, claims that in Venezuela there will never be a dollarization of the economy and that what actually exists is a set of “mechanisms of economic war and resistance that push to exchange products in other currencies and cryptocurrencies.”

What is the real proportion of this phenomenon? Sometimes, glasses are indeed required to observe and understand what is “in plain sight.” For this reason, Últimas Noticias decided to explore how the people of Venezuela really make payments, so as to get a better idea of how much the national currency has actually been displaced or not. With this aim, Últimas Noticias conducted a digital survey on its web portal and through its social media platforms, with the following question:

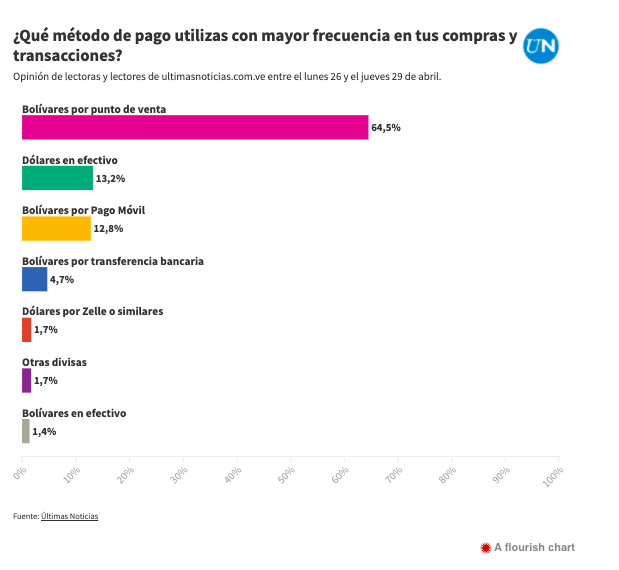

“What payment method do you use most frequently in your purchases and transactions?”

The options were: bolívars at points of sale, bolívars in bank transfers, bolívars for mobile payments, bolívars in cash, dollars in cash, dollars in Zelle or similar payment gateways, and other foreign currencies. From Monday, April 26 through Thursday, April 29, 2,950 responses were received, and the result was—the bolívar is alive!

The vast majority of users who responded to the survey affirmed that what they use most frequently to pay for goods and services are bolívars at points of sale. That number is about 64.5%, which is almost two-thirds of the responses. From the outset, it is clear that the bolívar is alive, and continues to have an important role in the national economic life.

After that, dollar cash payments were registered at a ratio of 13.2%. The most notorious expression of the so-called “dollarization,” the use of greenbacks, turns out to figure only slightly larger than a tenth in people’s day to day payments. To better appreciate this, the data can be compared with this observation—mobile payments with bolívars come in third place at 12.8%. This means that the number of people who pay mostly in cash dollars is almost equal to those who mostly use bolívars to make mobile payments. Bank transfers represent about 4.7% of all payments. On the other hand, payments in dollars through mobile applications, such as Zelle, as well as payments in currencies other than the dollar represent 1.7% in each case.

At last place came payments with bolívars in cash which corresponded to only 1.4% of the responses to the survey.

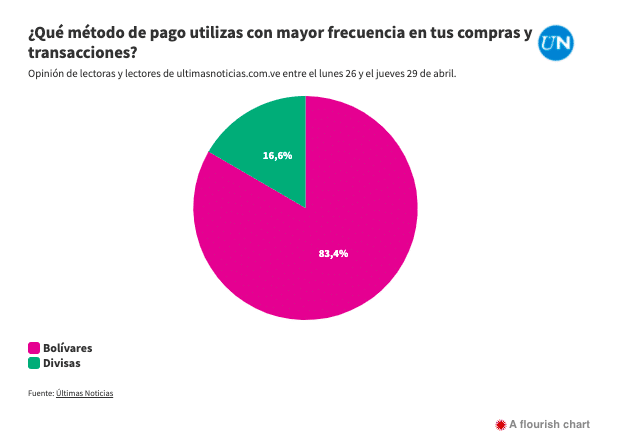

If the data is summarized, it can be seen that payments in bolívars amount to 83.4% of the survey responses, while foreign currencies represent 16.6%.

RELATED CONTENT: Credit Suisse’s ‘Suspicious’ Forecast for Venezuelan Economy: 4% Growth in 2021

Mastery by the digital realm

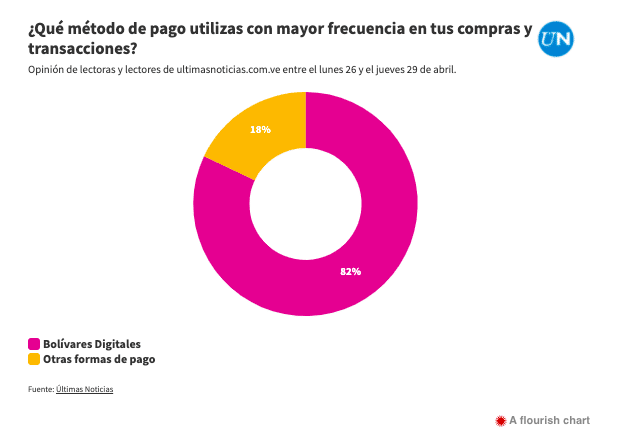

President Nicolás Maduro affirmed in an interview with Ignacio Ramonet on January 1 that during 2020, “77.3% of commercial transactions in the country were made in bolívars through digital payment methods.” In the featured survey, that figure rises up to 82%, grouping together payments in bolívars by point of sale, through mobile payments and by bank transfers.

The government has also stated that it plans to move towards a “100% digitization of the economy” this year, and in this regard it is worth highlighting the data obtained in the survey about the use of bolívars in cash. Considering payments in bolívars only, cash would represent only 1.75% of payments compared to 98.25% digital forms of payment. Although a new set of currency notes was put into circulation this year, everything seems to indicate that the country is seriously heading towards an abandonment of physical payments and their full replacement by digital ones. For example, there has been progress in the implementation of electronic collection mechanisms for urban transport, which apparently is the area in which bolívars are most used as cash.

Contrasts

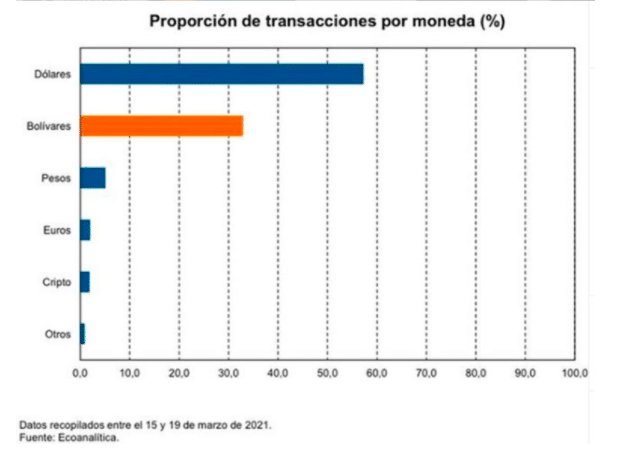

Últimas Noticias also looked for other data with the purpose of comparing with this survey and found that the private consultancy firm Econanalítica had published, in its social media accounts, the result of a study carried out in March on this very same topic. In an Instagram publication the organization asserts that commercial transactions by currency at national level are: dollars 57.3%, bolívars 32.9%, Colombian pesos 5.1%, euros 2%, and cryptocurrencies 1.9%. It claims that “67.1% of payments were made with a currency other than bolívar.”

Evidently the two results differ greatly, to the point that an almost opposite phenomenon is presented. In order to comprehend these results, Últimas Noticias consulted economist Pablo Giménez, professor of the Graduate Training Program in Political Economy at the Bolivarian University of Venezuela (UBV).

The academic pointed out that, first of all, it is necessary to pay attention to the type of survey carried out and that these consultants usually recur to samples of merchants and traders. Indeed, Ecoanalítica clarifies in its publication that its survey included “10 cities, 360 establishments, 7 items and more than 21,600 transactions.” Giménez pointed out that it would be necessary to know which cities of the country the consultant firm chose for its survey, and which urban sectors within those cities and what types of establishments were surveyed, if they were restaurants, grocery shops, or sellers of spare parts of vehicles.

“On the other hand,” continued Giménez, “when merchants talk about transactions, they take into consideration costs. It is not just about final purchases and sale operations, but of supplier operations as well, with other distributors and with wholesalers who provide the goods to be sold. So a merchant is looking at a broader set of operations, and is probably covering or calculating those costs in dollars and surely many of those operations do occur in other currencies or though banking operations and currency transfers. Contrary to this, consumers depend on their salary, and salaries in Venezuela are still mostly paid in bolívars.”

So, these are two different perspectives in regard to business transactions. The Últimas Noticias survey focused on the general public, without differentiating on which side of the trade transaction they were; still it is possible to assume that the vast majority are end consumers. Giménez pointed out that the differences can be explained through this type of bias in the surveys. However, he added that “if they are all final transactions, purchases made by the general public—most of them, indeed—should take place in bolívars”, as the Últimas Noticias survey shows. According to Giménez, it would be advisable to corroborate this information with the Banking Sector Superintendency (SUDEBAN) “so as to analyze the volume of daily transactions occurring in Venezuela, either by points of sale, or by mobile payments, or through bank transfers.”

However, that information is not available, at least not on the SUDEBAN web portal, which was consulted before this survey was released.

RELATED CONTENT: US Report Recognizes Impact of Sanctions on Venezuela’s Economy and Human Rights

Social differences

Perception of the so-called “dollarization” in Venezuela can vary according to the perspective from which it is viewed. As is evident in the study, the common people of Venezuela, working class people still use the national currency to a greater extent, although they also handle dollars up to a certain point. Meanwhile, there can be other sectors of the society in which “dollarization” is greater and the use of the bolívar has strongly diminished. This may be the case of business and commercial sectors of the country.

So, one has to be more specific when discussing a “dollarized economy,” or even just plainly mentioning “dollarization.” There are those who speak of a “dollarization process” as if this were an inevitable fate. But this would be inappropriate since, as has been pointed out at the beginning, the Venezuelan government has categorically rejected the possibility that the bolívar is going to be replaced any time soon by the dollar or by any other foreign currency.

What this conveys is the unequal dynamics and processes, typical of the situation in which the country finds itself at present. Although the bolívar continues to dominate transactions in volume, the dollar has taken center stage due to the role it has played in the economic dynamics. In Professor Pablo Giménez’s own words, “I prefer to use the term trade liberalization, or trade opening, which I think better describes what is happening in the country. This opening requires a setting of a much more objective exchange rate by market forces, as has been happening since May 2019 within the banking sector. This has effectively allowed greater volumes of transactions in dollars and foreign exchange flows, whether in cash or bank operations via transfer. So this is mainly a matter of dollar transactions; and given the crisis of the bolívar, the dollar is able to maintain its value and serves as the main unit of account for economic transactions.”

This allows people to resolve problems in their everyday transactions. However, its impact varies according to social class, and also depends on the productive area or the economic sector in which the transactions are operated. Workers who can access even a small volume of foreign exchange can better protect their income; and the commercial sector can maintain a volume of transactions that allows a certain “dynamization” of the economy in the current Venezuelan context. “As is well known,” explained Giménez, “we have already experienced 6 years of continuous fall of GDP, and from December 2017 to May 2019 we were in a situation of hyperinflation. There was the drop in oil prices in 2014 as well, and since 2015, we have progressively become a blockaded country in commercial and financial terms.”

Giménez added that, given the current situation, this transactional volume of foreign currency allows the economy to function in commercial areas as well as in the manufacturing and agricultural sectors. Workers in these sectors “are seeing an improvement in their income little by little as a result of these operations; some business owners are already remunerating their workforce directly in foreign currency.”

In conclusion, the analyst gave a suggestion with which Últimas Noticias agrees. In his opinion, it would be interesting to broaden the general scope of the economic perspective and complement it with further analysis by carrying out a “very objective study focused on how the workforce in Venezuela is getting paid.”

Featured image: A customer paying in dollars in December 2020 at a supermarket in Caracas. Photo courtesy of EFE

(Últimas Noticias) by Ángel D. González

Translation: Orinoco Tribune

OT/GMS/SC

You must be logged in to post a comment.