Classified Documents Invalidate United States’ Appeal Against Assange

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

By Richard Medhurst – Nov 29, 2021

The United States broke diplomatic assurances for David Mendoza. It will do the same with Julian Assange.

David Mendoza Herrarte was born and raised in the United States. His mother being from Spain, he would go there every summer, describing it to me as his second home. He is both an American and Spanish national.

Mendoza was wanted by the United States for drug trafficking. In the early 2000s, he used helicopters to transport marijuana, known commonly as BC Bud, from Canada across the US border into Seattle. Today, marijuana is legal in Seattle.

Mendoza worked in building and property development, making good money. He told me he only did this on the side to help subsidize some of his building projects: “I had so many things going on, but I should have never done it to begin with. Too much ambition in my mid-twenties.”

Mendoza first realized US authorities were on to him when he was rear-ended by a truck while driving, causing the bumper on his car to fall off. When he took it to a repair shop, the mechanic informed him that a GPS tracker which read “property of the federal government” had been placed under his car.

Mendoza tells me that teams were put on him to surveil him 24 hours a day. While casually chatting to a neighbor, he finds out the government had rented property across the street from him, which another neighbor had been trying to lease forever, with little success, at an astronomical rate of $6,000/month.

To avoid arousing suspicion, Mendoza knew he couldn’t just fly out the country, as he’d likely be stopped at the airport. Instead, he exchanged cars with a waitress working at one of his restaurants, and unbeknownst to her, drove for 20 hours straight to the Mexican border.

Once in Mexico, he stayed at a house that he owned for about a month, until he caught wind that an international arrest warrant was out on him. He left Mexico and headed to Madrid, arriving in Spain in June 2006.

Two years later in June 2008, Mendoza was arrested by Spanish police under an international arrest warrant. The United States had requested his extradition on drug-related and money laundering charges.

At this point, Mendoza had already settled in Spain and started a family. He was now married with two kids.

Mendoza told me, “In Spain if you get sentenced, they send you as close as possible to your family. You have open visits, conjugal visits, your child can be with you. In many cases the children live with the mother. The idea is to maintain the nucleus of family.”

Judges took into account that Mendoza was now living in Spain, married, and his first child, barely 9 months old, was born with down syndrome. He had another child, just conceived, also on the way—both Spanish nationals. In light of these conditions, Mendoza asked the court to take his family into consideration.

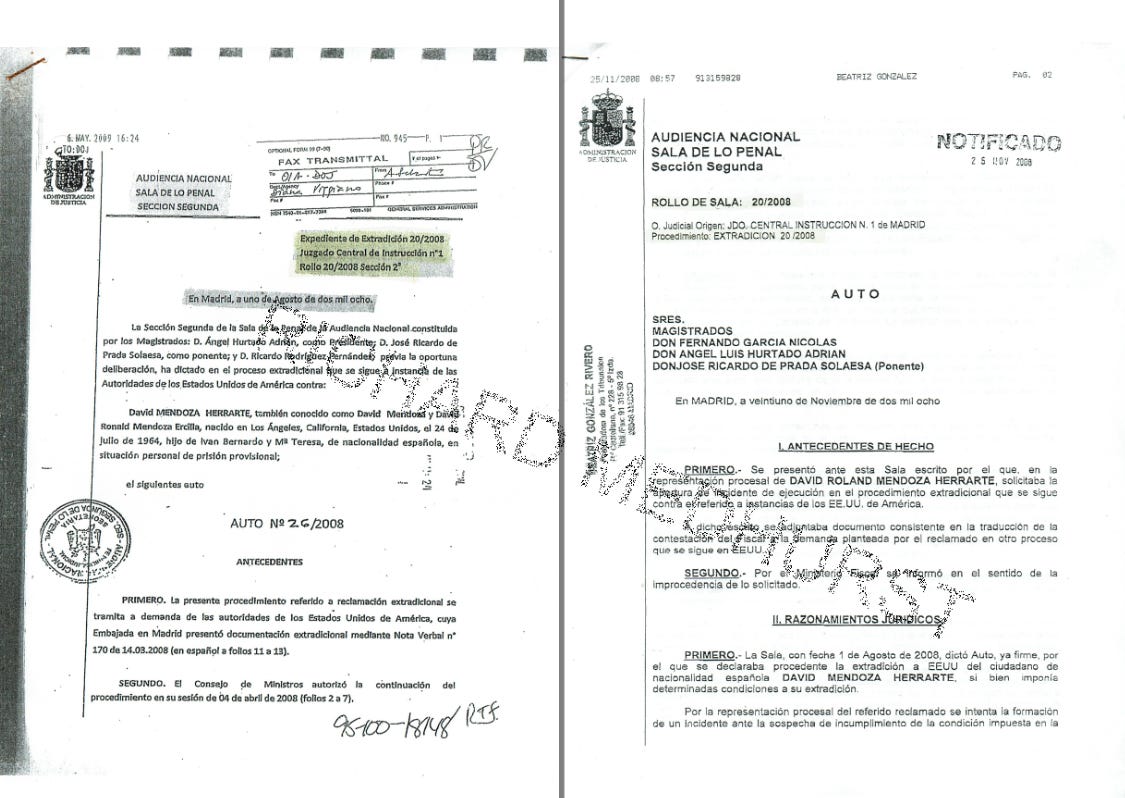

August 2008: The Spanish National Court ruled that Mendoza’s extradition to the United States could only proceed under three conditions: (1) that he serve any sentence in Spain, (2) that no life sentence be given, and (3) that he would not be tried for currency structuring.

US prosecutors rejected this, arguing that the US-Spain Extradition Treaty did not allow for Spain to condition transfers.

November 2008: The Spanish Court responded with a second ruling. It reiterated that it does have the power to impose conditions on the extradition of a Spanish national.

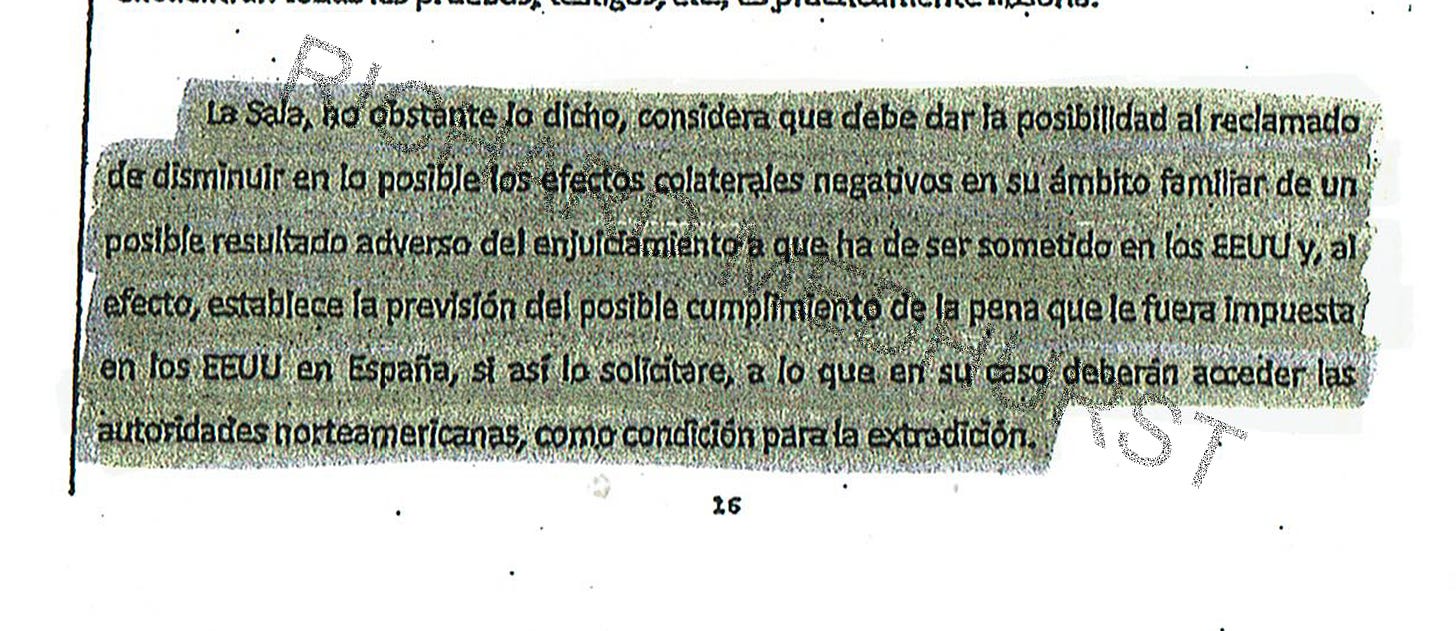

In both rulings, Spanish judges had made their position unequivocal: if the United States wanted to extradite Mendoza, it had to send him back to Spain to serve his sentence.

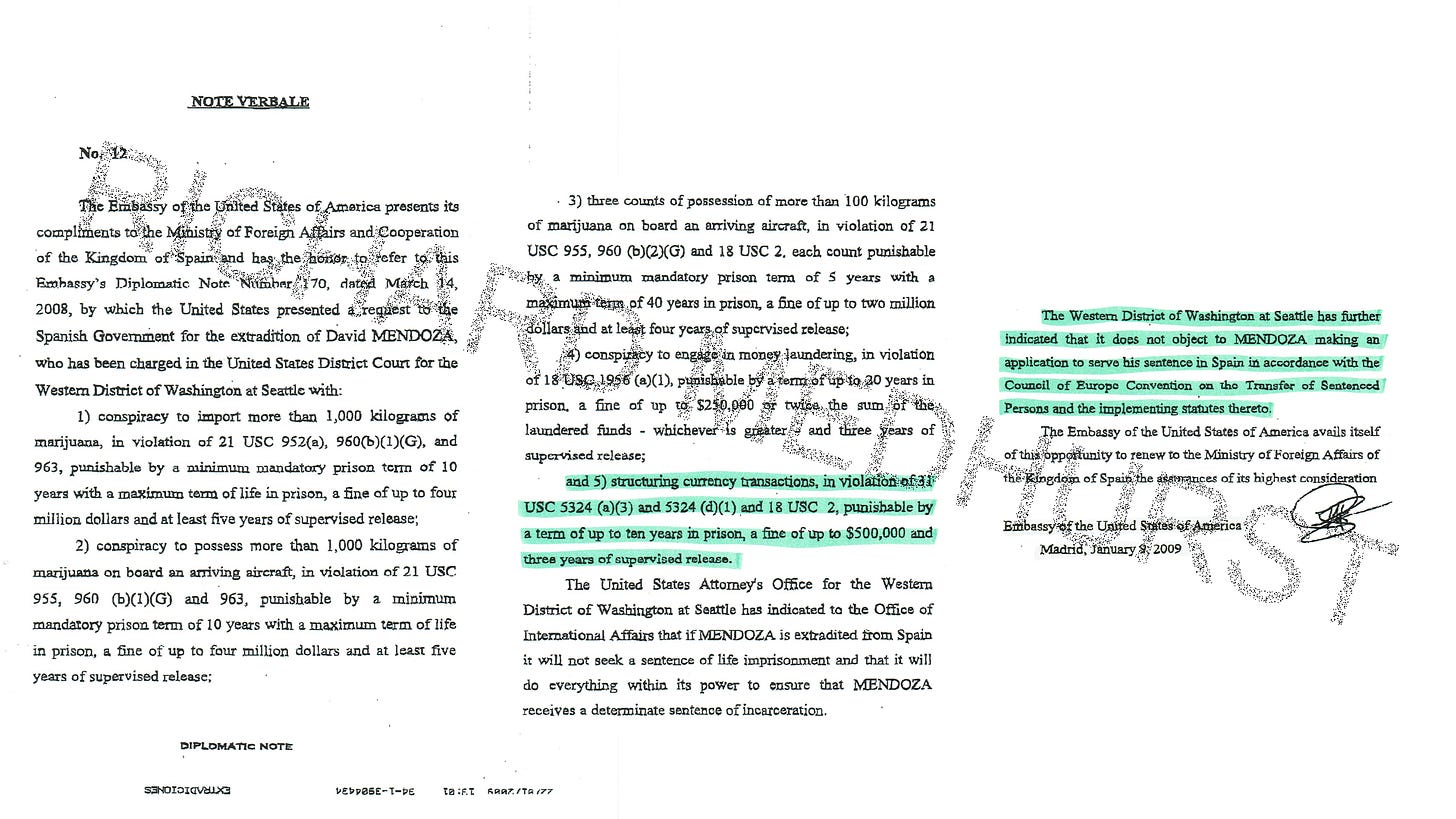

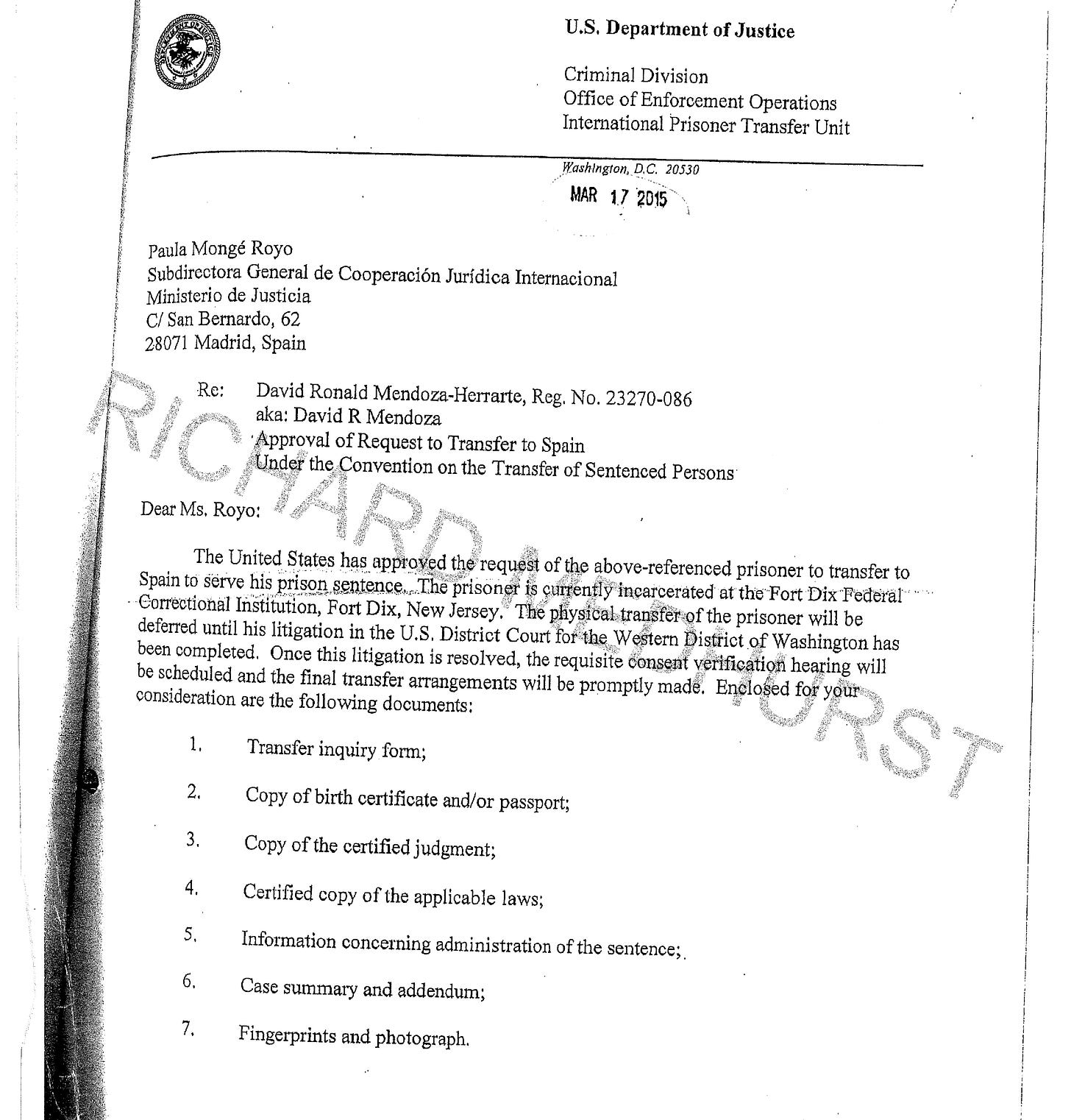

January 2009: The US Embassy in Madrid sent the Spanish government a verbal note containing diplomatic assurances regarding David Mendoza.

It listed all the charges brought against Mendoza, including the currency structuring charge, despite this being explicitly ruled out by the Spanish Court. This is because no equivalent exists under Spanish law. A life sentence was ruled out for the same reason, as life sentences are not permitted in Spain and the extradition must be compatible with Spanish law.

The diplomatic assurances given to Spain by the United States read: “The Western District of Washington at Seattle has further indicated that it does not object to MENDOZA making an application to serve his sentence in Spain in accordance with the Council of Europe Convention on the Transfer of Sentenced Persons and the implementing statutes thereto.”

This diplomatic “assurance” immediately raised eyebrows

The diplomatic assurance did not specifically state that Mendoza would be sent to Spain to serve his sentence. It only said that the United States “does not object to Mendoza making an application to serve his sentence in Spain”—something the United States cannot object to anyway, as it is every prisoner’s right to apply for a treaty transfer.

Mendoza tells me, “This shows the deviance of these people. They use this ambiguous language on purpose. There’s precedent in federal court that if they don’t specifically agree to the transfer, it’s not valid.”

Recently, the United States offered similar diplomatic assurances to the United Kingdom, namely that Assange could serve a sentence in his home country of Australia.

Mendoza says for this to be valid, the diplomatic assurances from the US must explicitly state in advance that the US Department of Justice and Australia accept Assange’s transfer—otherwise it’s meaningless.

“With the Assange thing, I can see it black and white,” says Mendoza. “They [Australia] are not going to do a thing. Under the treaty, all three parties must agree: Julian, Australia, and the United States. But the US can tell Australia behind the scenes: ‘screw this guy, don’t do anything.’”

The Convention on the Transfer of Sentenced Persons specifically states under Article 3(f) that a sentenced person may be transferred “if the sentencing and administering States agree to the transfer.” (The administering state here meaning Australia)

Being one of the few journalists to cover Assange’s extradition, I can confirm that as of now Australia has not given any indication that it would accept Julian Assange’s request to serve a sentence there, should he apply.

In its rulings, the Spanish National Court had also explicitly stated that Mendoza cannot be given a life sentence, or equivalent term of confinement if extradited. The diplomatic note did say that US prosecutors “will not seek a life sentence of imprisonment,” however, they would ensure “Mendoza receives a determinate sentence of incarceration”—which could mean any number of years and does not explicitly comply with Spain’s conditions.

While the United States’ diplomatic assurances to Spain may have been vaguely worded, the next document signed by the US Embassy certainly wasn’t.

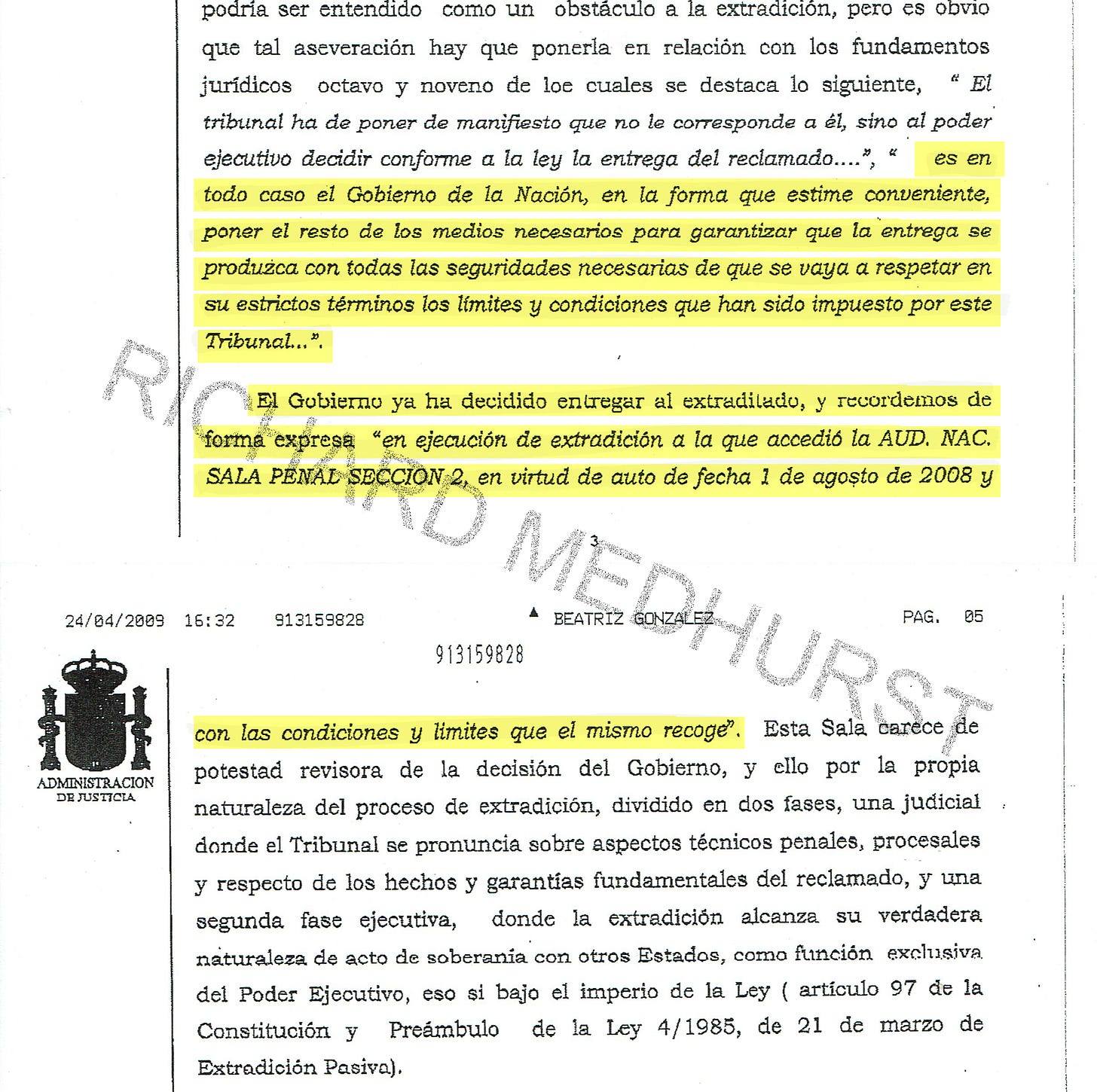

April 2009: Mendoza showed the United States’ diplomatic assurances to the Spanish court, complaining they were too ambiguous. The Court then explicitly ordered the Spanish government to “take all the necessary measures to guarantee” that the United States would respect all the conditions of his surrender [and extradition].

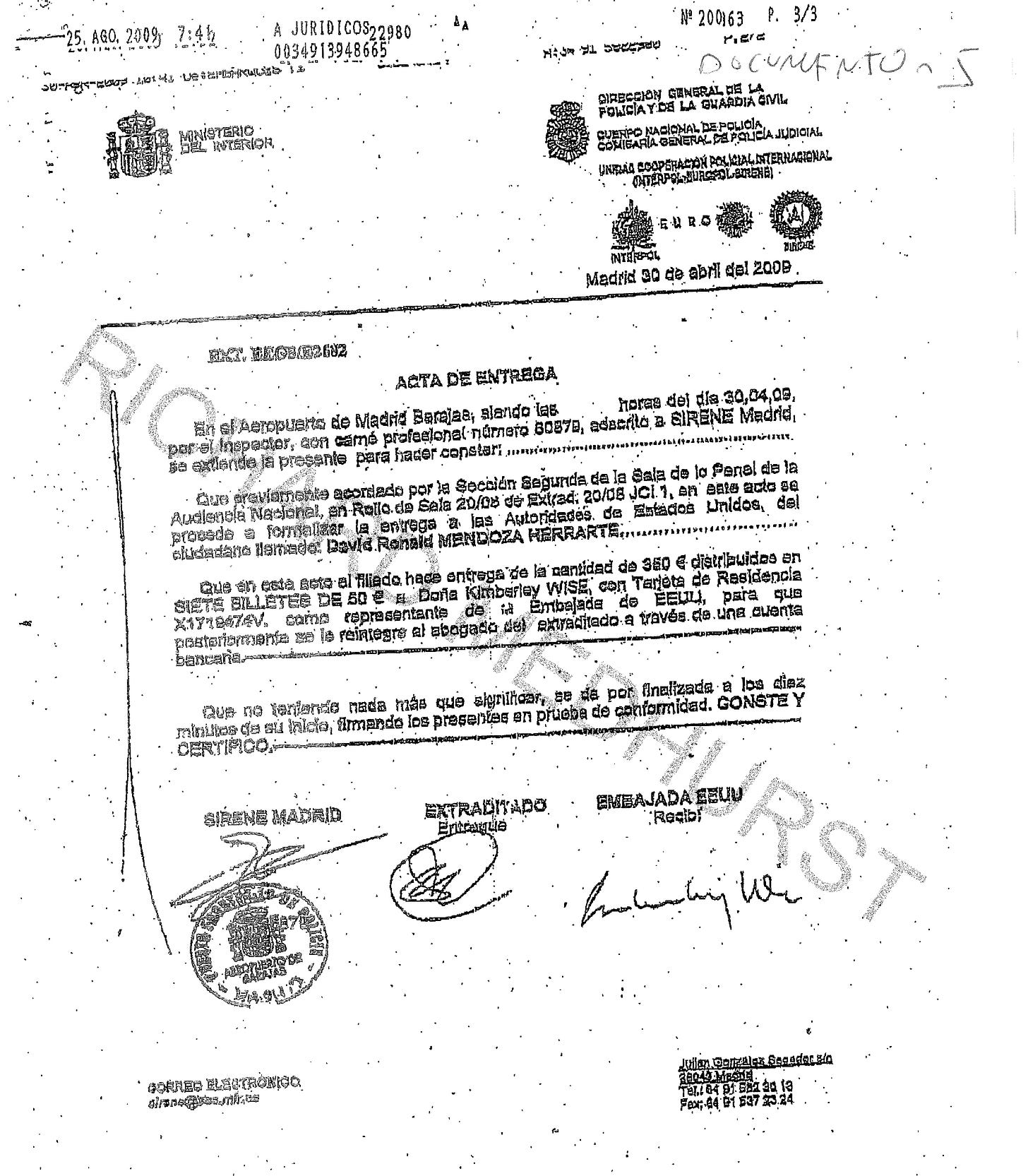

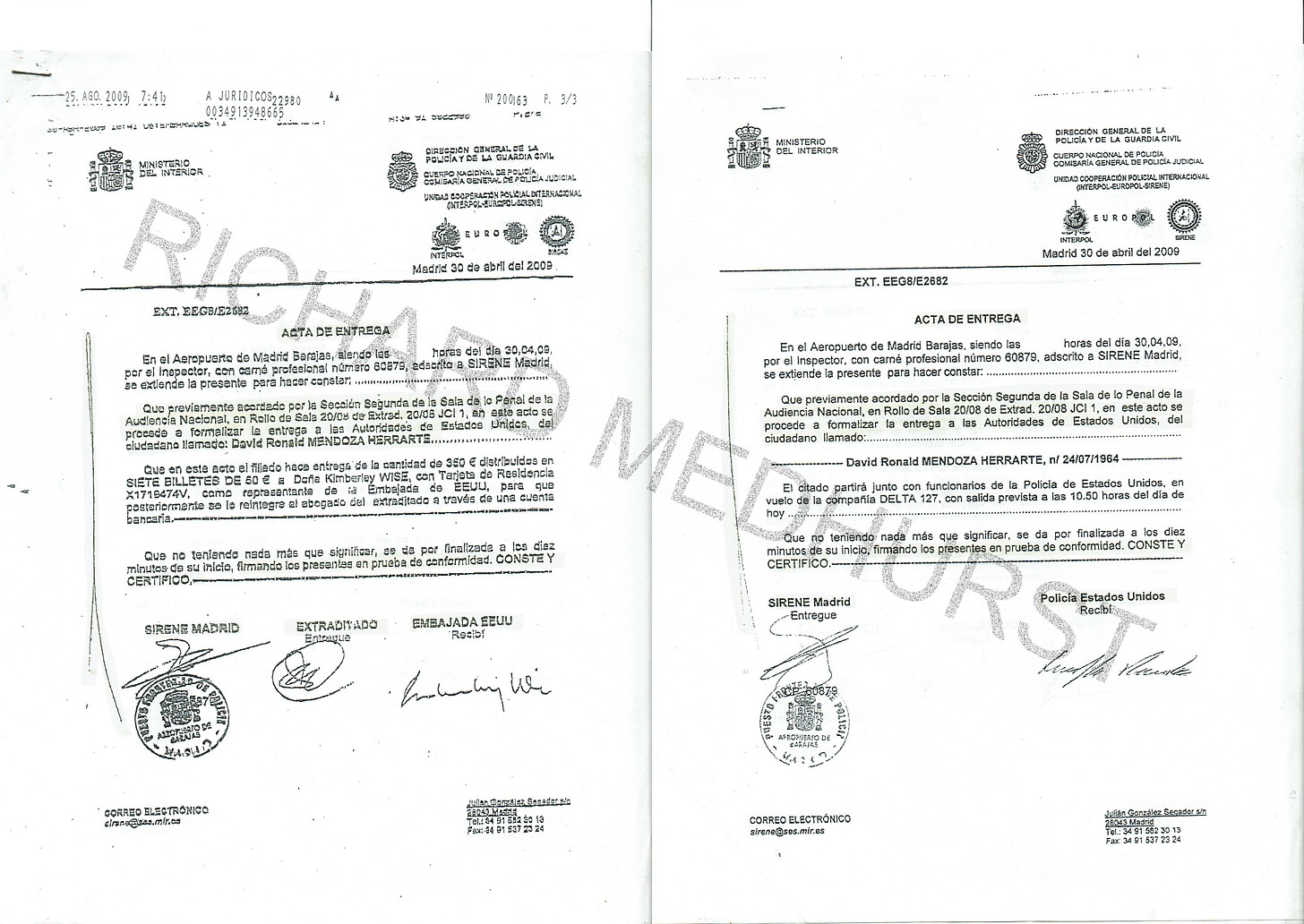

As a result, a contract for Mendoza’s extradition was established: the Acta de Entrega or Deed of Surrender.

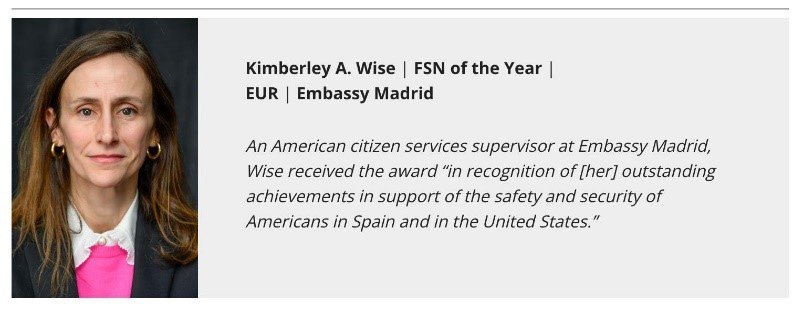

As Mendoza stood on the tarmac at Barajas airport, ready to be extradited to the United States, he was accompanied by Spanish police and a Spanish diplomat. Waiting for him were US Marshalls and a representative of the US Embassy in Madrid, Kimberley Wise.

Mendoza was stripped, placed in an orange jumpsuit and shackles, and told to sign the Acta de Entrega.

The Acta de Entrega is a crucial document. It states that Mendoza was handed over to the United States authorities, and more importantly, it confirms that he was handed over “in accordance with what was previously stipulated by Section Two of the National Criminal Court”. Meaning whoever signs this document agrees to the terms and conditions imposed by the Spanish court, i.e., that Mendoza must serve his sentence in Spain.

Kimberley Wise signed the Acta de Entraga on behalf of the United States government, agreeing to the conditions of Mendoza’s extradition. Wise signed it together with Mendoza, and a representative of the Spanish government. All three signatures on the Acta de Entrega are shown below.

Leaving no room for ambiguity, Mendoza recalls how a Spanish court official held up the paper in front of everyone, and specifically asked: “Do you all understand what you are signing?”, highlighting the text with a squiggle, still visible on the left side of the page.

Despite reading and signing this document, the United States government would never allow Mendoza to see it again, saying it was classified and that he was not privy to diplomatic communications.

Kimberley Wise, who signed the Acta de Entrega on behalf of the United States, can be seen still working at the US embassy in Madrid as recently as 2019.

In an interview with the State Department’s magazine, Kimberley Wise boasts about her close relationship with the Spanish legal system: “I know the police. I know the prosecutors.”

When I showed this video to Mendoza, he immediately recognized Wise. “It’s disgusting how these people are so integrated into Spain’s justice system—and with such arrogance, as if she controls them.”

April 2009: David Mendoza Herrarte is extradited to the United States

After signing the Acta de Entrega, Mendoza was officially under US jurisdiction. He recalls being handed over to US authorities: “The first thing they do when they get you, is they strip you naked. The marshals look in your mouth, your ass, your ears, every orifice. They attempt to humiliate you in every fashion: ‘Squat! Now do this…’. They tell you: you’re under US jurisdiction now, and our law is what is going to apply to you.”

June 2009: Once in the United States, Mendoza took part in what is known as an arbitration hearing or settlement conference. This is where plea bargains are hashed out in the presence of the judge, between prosecutors and defendant.

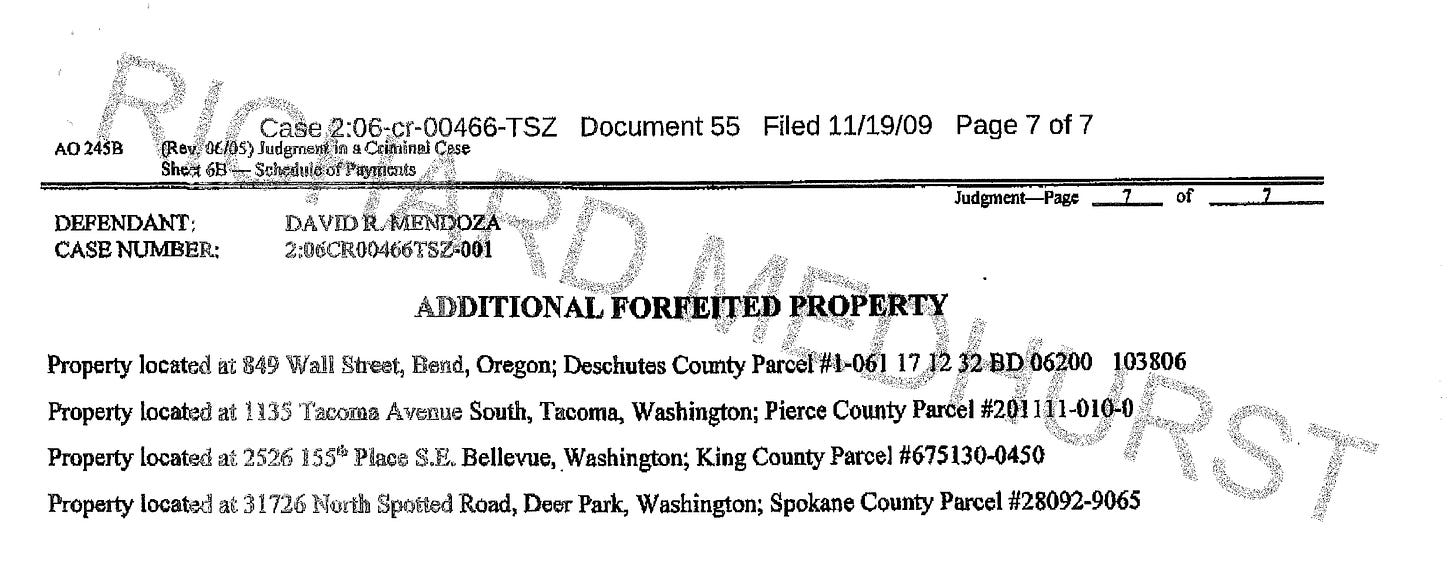

Prosecutors threatened Mendoza with over 20 years in prison if he didn’t hand over more of his property.

“I had a very large building in Tacoma, Washington worth $2 million. The feds wanted to seize it but couldn’t, it was in my wife’s name, it had no association to narcotics.”

Mendoza was told that if he handed over the building, the US government would not oppose his transfer request to Spain. Mendoza asked them to put it in writing. He was told no; that this wasn’t common practice during arbitration. The judge, Ricardo Martínez, reassured him that he’s there to make sure the government keeps its word.

Mendoza reluctantly handed over the property, thinking it would improve his chances of getting back to Spain. “Right as I got into town, I could see it was all about money. They wanted me to give up everything.”

The Assistant US Attorneys present were Susan Roe, Roger Rogoff, and Richard Cohen. All decisions had to go through Jenny Durkan, the lead prosecutor against Mendoza. Durkan is now the mayor of Seattle, WA.

At this point, the US government had already seized $14 million of Mendoza’s assets and properties, the overwhelming majority with no relation to narcotics.

During sentencing Mendoza was now looking at 14 years in prison. Mendoza told the judge: “Your honor, the prosecution’s estimate is that I made $2 million from marijuana, yet you guys have taken $14 million of my property. Where’s the balance of justice here? Take $2 million, and I keep 12. Every hour of my life I worked on these buildings.”

Thomas Zilly, the senior District Judge, looked down at Mendoza and told him: “Young man, in the United States of America, when you mix one dirty penny with a hundred clean pennies, it becomes United States property.”

Mendoza explains to me, “Before I was even indicted or extradited, they seized my property and indicted my property in civil court.”

“On every property I owned they posted signs that it’s being seized by the federal government and that I had 90 days to challenge.”

Mendoza suspects the government was trying to trap him by getting him to return to the US to challenge the seizures in court, because they didn’t have enough evidence tying him to narcotics.

“I hired an attorney to challenge the seizures. But one of the games the government plays is that you can’t challenge a civil suit outside the United States. You have to be there yourself. That was a tactic to force me back to the United States. They indicted all my property; they didn’t care whether it was used in the crime or proceeds—they took all of it.”

At sentencing, Mendoza asked that the court respect the conditions of the extradition and send him back to Spain to serve his sentence. Mendoza recalls the following exchange:

Judge Zilly: Mr. Mendoza, do you know under what instrument you were extradited to the United States?

Mendoza: Yes, the Extradition Treaty between Spain and the United States of America.

Judge Zilly: That’s correct. And are you a signatory to this treaty? Did you sign it?

Mendoza: No, I did not. Spain and the United States signed it.

Judge Zilly: That’s correct. Unless you’re a signatory of this treaty, you have no claim.

It now became clear that the United States never intended to send Mendoza back to Spain. They had squeezed him for every last penny, then violated the diplomatic assurances given to Spain.

What the United States was essentially saying is: Mendoza isn’t a signatory of the Spain-US Extradition Treaty; therefore he can’t sue for breach of contract if the US doesn’t send him to Spain.

That might sound like a ridiculous statement because it is. Obviously, Mendoza isn’t a signatory of the extradition treaty because treaties are signed between countries, not natural persons.

Mendoza expects the United States government will play the same trick on Assange if they refuse to send him to Australia and he contests it in court.

“Within that note, it must specifically state that Julian has a right to contest non-compliance of the United States, even as a non-signatory to the treaty. Because the US will start playing games.”

In Mendoza’s case, however, there was a document that he, the United States and Spain had all signed together, which clearly stated that he must serve his sentence in Spain: the Acta de Entrega.

Mendoza asked for a copy under a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request but was denied. Instead, he was given another version of the Acta de Entrega, with his signature missing. The version given to him by the US only bore the signatures of the Spanish and US authorities (left) instead of the original version (right) signed by him, Spain, and the United States.

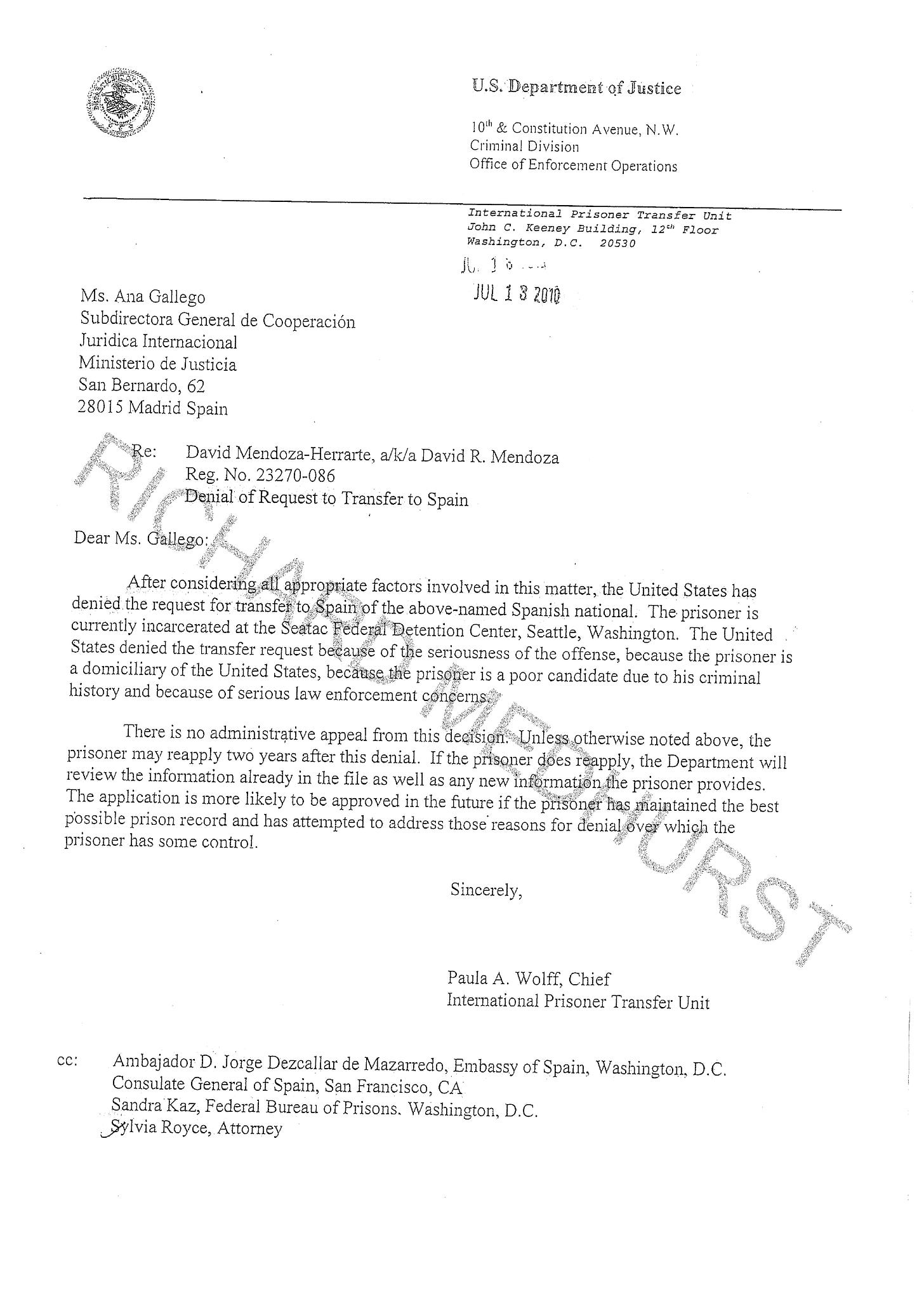

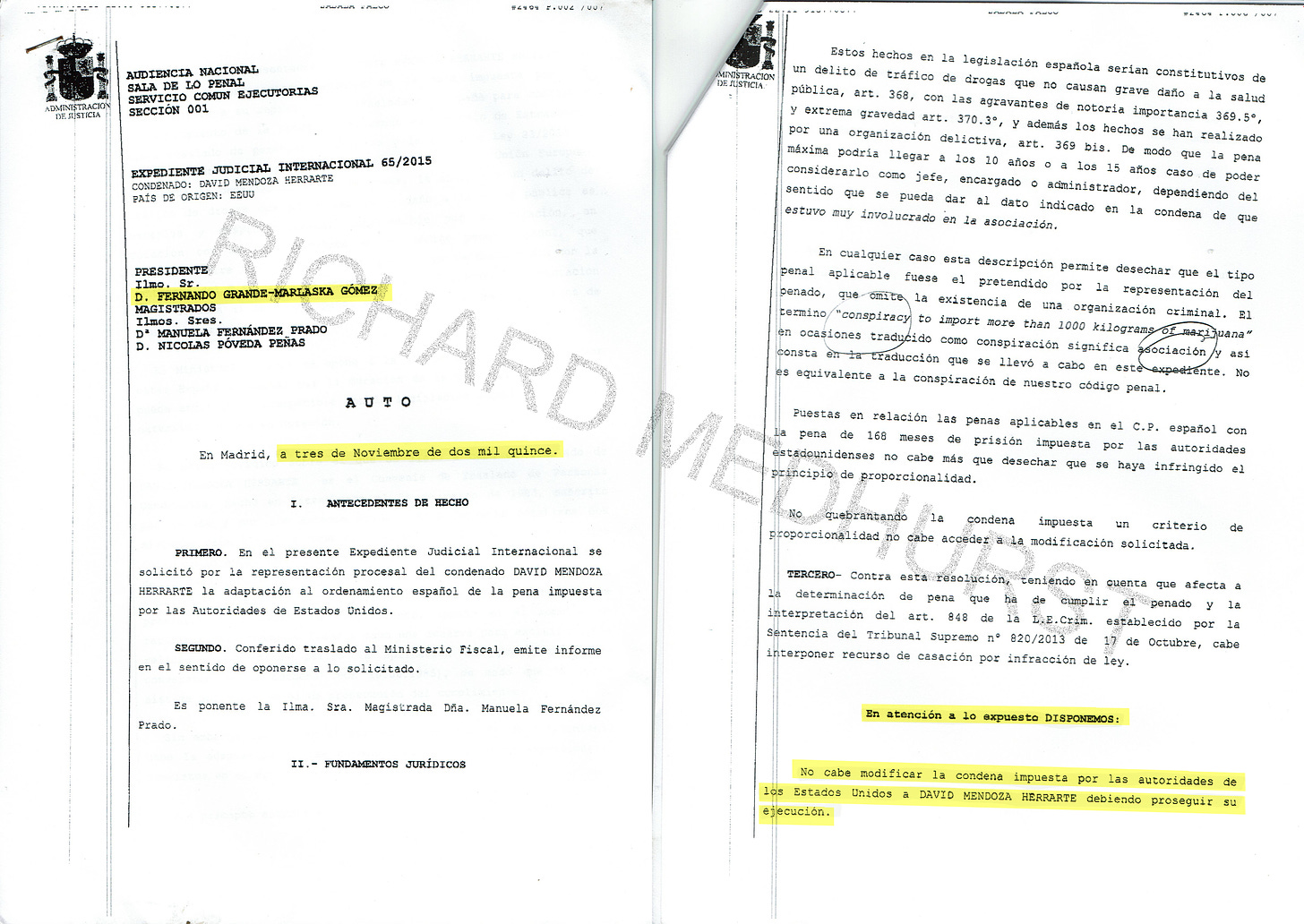

Mendoza was sentenced to 14 years in prison. Instead of being sent to Spain immediately to carry out his sentence, Mendoza was told to apply for a treaty transfer. He applied, and the answer from the United States was “no.”

“The United States denies the transfer request because of the seriousness of the offense, because the prisoner is a domiciliary of the United States, because the prisoner is a poor candidate due to his criminal record and because of serious law enforcement concerns,” was the response to his application.

In total, Mendoza applied three times for treaty transfer to Spain. All three applications were denied, violating the conditions of his extradition. Each time he applied, he had to wait 8 months for a decision, and even longer to apply again. The denial states: “There is no administrative appeal from this decision. Unless otherwise noted above, the prisoner may reapply two years after this denial.”

Mendoza told me: “That’s when I realized I’m in the wrong court. I’m going to get nothing here. I’m going to sue my own country because at least I might have a little taste of justice there.”

After the first denial in 2010, Mendoza sued Spain in criminal court, asking Spanish judges to enforce the extradition conditions, i.e., return him to Spain. At first, the lower courts told him there was nothing they could do. Then the case went to the Criminal Supreme Court, which refused to touch it.

Two years had gone by, and Mendoza was getting nowhere in the criminal courts. His next move was to try the Spanish Constitutional Court, which also refused to take his case, nor compel the Americans to hold up their end of the deal.

The third and final option was the civil court.

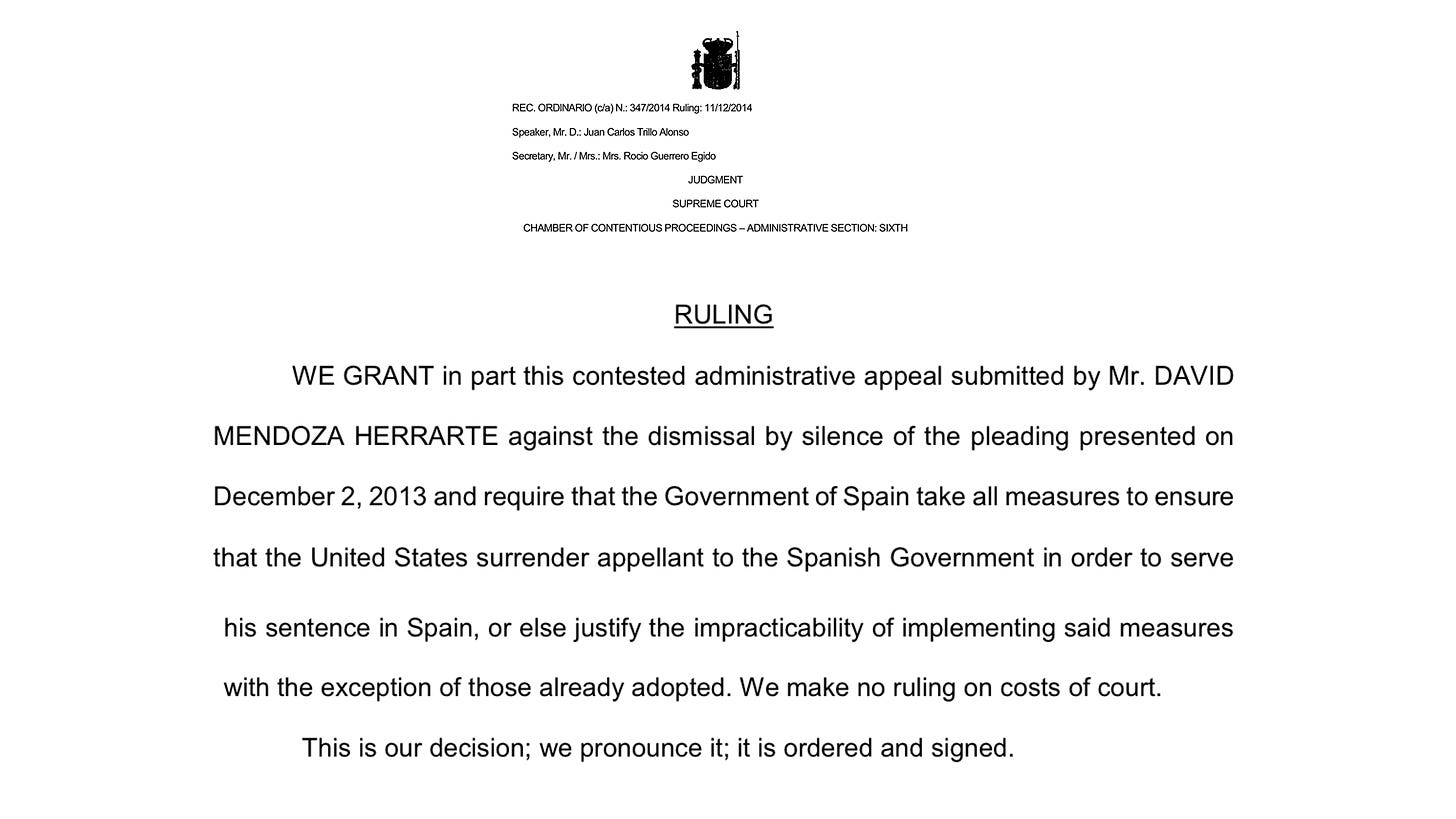

In 2014, Mendoza filed two lawsuits against Spain: (1) that the conditions of his extradition had been violated, and (2) that his human rights had been violated. Each case went to the Supreme Court. Mendoza won both.

The Spanish Supreme Court found the government’s efforts to retrieve Mendoza from the United States to be inadequate and laughable. The Spanish government was ordered to hand over diplomatic communications with the US—which it had previously refused to give Mendoza. They revealed that Spain had only asked the Americans to send Mendoza back two times.

The Spanish government was ordered to “take all measures to ensure that the US surrender the appellant [Mendoza] to the Spanish government in order to serve his sentence in Spain.” If not, the Supreme Court would use all the tools at its disposal to do so. In other words, the Supreme Court threatened to suspend the extradition treaty between Spain and the United States altogether.

That’s when the United States finally began to feel some pressure.

“Once the Spanish Supreme Court came out with that ruling, they started shitting their pants,” Mendoza explains. “If Spain’s courts suspended the extradition treaty, there is a huge process to get it back in again. It has to go through the Spanish Congress, the EU, and would attract too much attention. They like doing these things under the radar, the last thing they want is to have this in public.”

In 2014, shortly before the Supreme Court ruled in Mendoza’s favor, Spanish diplomats visited him in prison. They put a piece of paper in front of him and said if he signed it, he’d be on his way back to Spain immediately. Apparently, the United States wanted five Colombians who were in Spain, which they were willing to swap for Mendoza.

Mendoza flat out refused. He wasn’t going to be responsible for helping extradite five Colombians, not to mention this was never part of the deal.

The diplomat was outraged by Mendoza’s refusal to comply. “She had a look of shock on her face and told me in Spanish: why are you always making everything so difficult?”

Mendoza snapped at her: “Madam, you are making things difficult. You’re the ones not following the court order. The court order doesn’t say 5 Colombians or 5 Germans in exchange for Mendoza.”

Mendoza suspects this was a manipulation tactic. He says the government probably caught wind that the Supreme Court was going to rule in his favor, so they wanted to get him back to Spain as fast as possible before the ruling caused any rift with the United States.

At the same time Mendoza was suing Spain from his jail cell in the US, pressure was mounting inside the country.

While in prison, Mendoza wrote to every single member of the Spanish Parliament. Every week, he would send out bundles of letters addressed to MPs, judges, lawyers, and others, trying to raise awareness about his case.

Mendoza tells me how he spent his days in prison at the law library, learning criminal law, familiarizing himself with extraditions, and discovering how the United States government had broken assurances many times before.

Support for Mendoza grew considerably inside Spain. When Spanish judges learned of what was going on, they became disgruntled with the United States refusal to uphold the conditions of his extradition. They began applying pressure on the US in their own way and stopped processing extraditions of Spanish nationals.

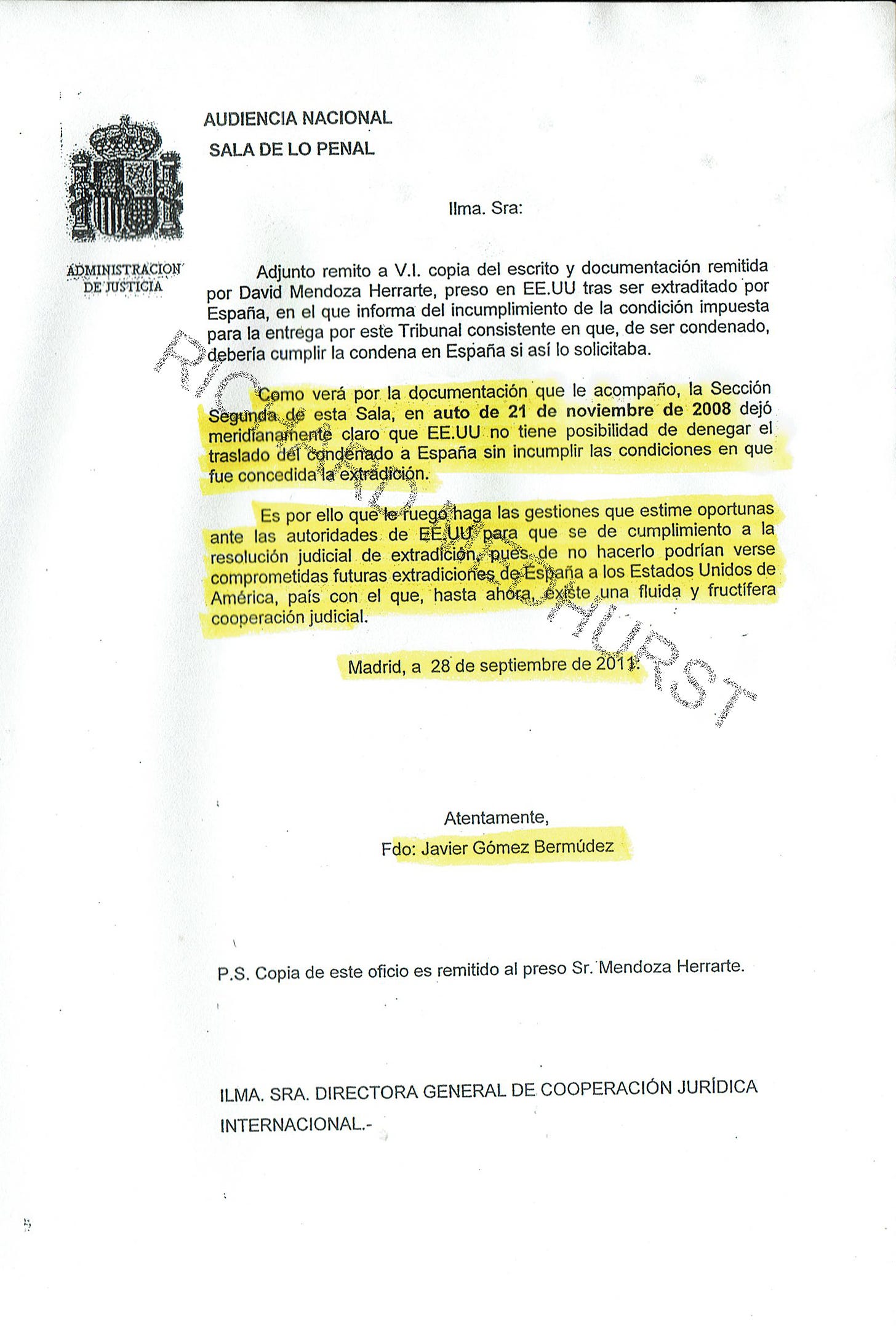

To drive the point home, Gómez Bermúdez, a senior judge in the Audiencia Nacional called in the US Ambassador to Spain, and wrote a deposition saying the Spanish Courts “made it crystal clear that the US does not have the possibility to deny the transfer of [Mendoza] to Spain without being in violation of the condition under which his extradition was allowed.”

He told them they had better return Mendoza “because not doing so could compromise future extraditions from Spain to the United States, a country in which up to this moment has existed a fluent and fruitful legal cooperation.”

He sent the same order to the Minister of Justice.

Another lucky break for Mendoza came through the mail, hidden in a stack of court documents. A Spanish judge had anonymously sent him a copy of the original Acta de Entrega: the contract that he, the United States and Spain had all signed together.

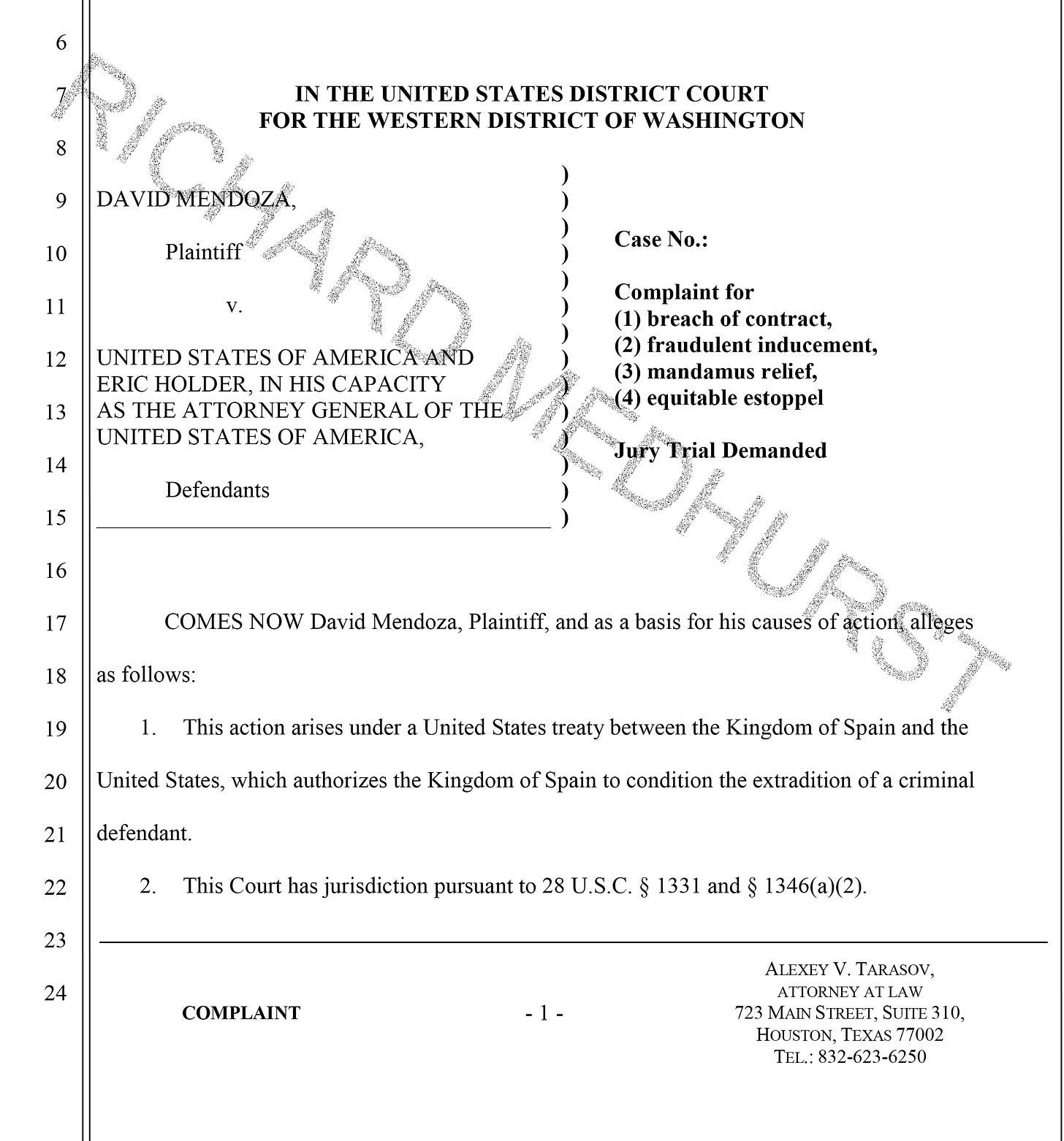

This meant that Mendoza could now sue the United States government for breach of contract for not sending him to Spain. Which is exactly what he did.

Mendoza filed a civil suit against the government of the United States and Eric Holder, Obama’s Attorney General.

Mendoza sued the United States on four counts. In court, the US attorney claimed that the Acta de Entrega was not a contract, but a receipt for €350. Mendoza called him an idiot and asked if he got his law degree in a Cracker Jack box, which caused the judge to giggle a little.

Alexey Tarasov represented Mendoza when he sued the United States. Tarasov tells me that as he was buying plane tickets to go to court in Seattle, he got a phone call from the US prosecutor there who informed him that if Mendoza dropped the civil suit, they would let him go to Spain immediately.

The pressure Mendoza was able to apply from inside his jail cell, suing both Spain and the United States, seemed to have worked—for now.

Paula Wolff was head of prisoner transfers at the Department of Justice at the time. She was in constant communication with the CIA, FBI, DEA, and State Department. In order to leave for Spain, every single one of these agencies had to approve the transfer.

Before he could leave, Mendoza was brought before a judge, along with other prisoners being processed for extradition. Mendoza was told to sign a paper that he would serve his full sentence once back in Spain. He refused, saying that this wasn’t part of the deal. This caused a holdup and the judge called recess. Mendoza suspects the judge likely called someone in Washington DC and was told to just let Mendoza go and be done with the whole story, as he was causing them too much trouble.

“The US lawsuit was just a financial thing to get all my property back, but what really worried them was the fear of losing the Extradition Treaty with Spain,” he told me.

Mendoza was allowed to return to Spain, but he tells me, “Dropping the suit against the United States is the biggest regret of my life.”

“They didn’t want to be liable in civil court for breach of contract. I was going to ask for all my property back until they made good on the agreement.”

While in prison Mendoza had studied the law books; how Americans had sued other countries from inside the United States, in federal court. He was inspired to do the same: “When I got back to Spain, I said I’m going to sue them [the US] under the same contingencies.”

Much to his surprise, however, he found that this was no longer possible. Spain had passed a new law on state immunity in 2015.

In total, Mendoza had spent 6 years and 9 months in the United States prison system. Each day in violation of the US-Spain Extradition Treaty and the conditions imposed by the Spanish National Court.

When Mendoza returned to Spain in 2015, he was originally told by Judge Grande-Marlaska that he would be freed. Three days later, however, Grande-Marlaska abruptly changed his mind. Mendoza suspects the Americans pressured him.

He upheld Mendoza’s 14-year sentence, because the law in Spain had been changed in 2014, raising the sentence from 6 to 15 years. Marlaska has since been promoted to Interior Minister.

Marlaska’s logic was that Mendoza had been transferred in 2015, so he had to apply the law at that time. However, Mendoza’s criminal activities took place in the early 2000s and he was sentenced in the US in 2009.

Mendoza told the judge, “Your honor, you can’t sentence me retroactively. You have to apply the law from when I was sentenced, when the crime was committed.”

Retroactive sentencing is forbidden under the United Nations, the European Convention of Human Rights, and the Spanish constitution. Laws are usually only applied retroactively if they benefit the convicted person, i.e., reducing a sentence or expunging records.

Mendoza says: “If Spain and the United States had done what they were supposed to under the agreement, I would have been back in Spain at the end of 2009. There was no ‘new law’ then. I would have done a few more years in Spanish prison, I had already done 2 years in the US at that point. Instead, I did almost 7 years in the US and then 4 years in Spain.”

Mendoza suspects the new sentencing was done to spite him. “This is their way of saying: you may force us to send you back but you’re not getting away with it.” He thinks that Kimberley Wise, the US diplomat present at his extradition, had something to do with it.

In Spain, Mendoza didn’t get out of prison until 2019. “I got out under conditional release, which is allowed in Spain, after serving two-thirds of your sentence for non-violent crimes. They said you can go home and report every six months.”

Mendoza told me that after he got back, Spain stopped requiring the United States to send back prisoners to serve their sentences in Spain—probably to avoid upsetting the United States. Spain still asks for ‘no life sentences’ but serving a sentence in Spain is no longer a condition they impose.

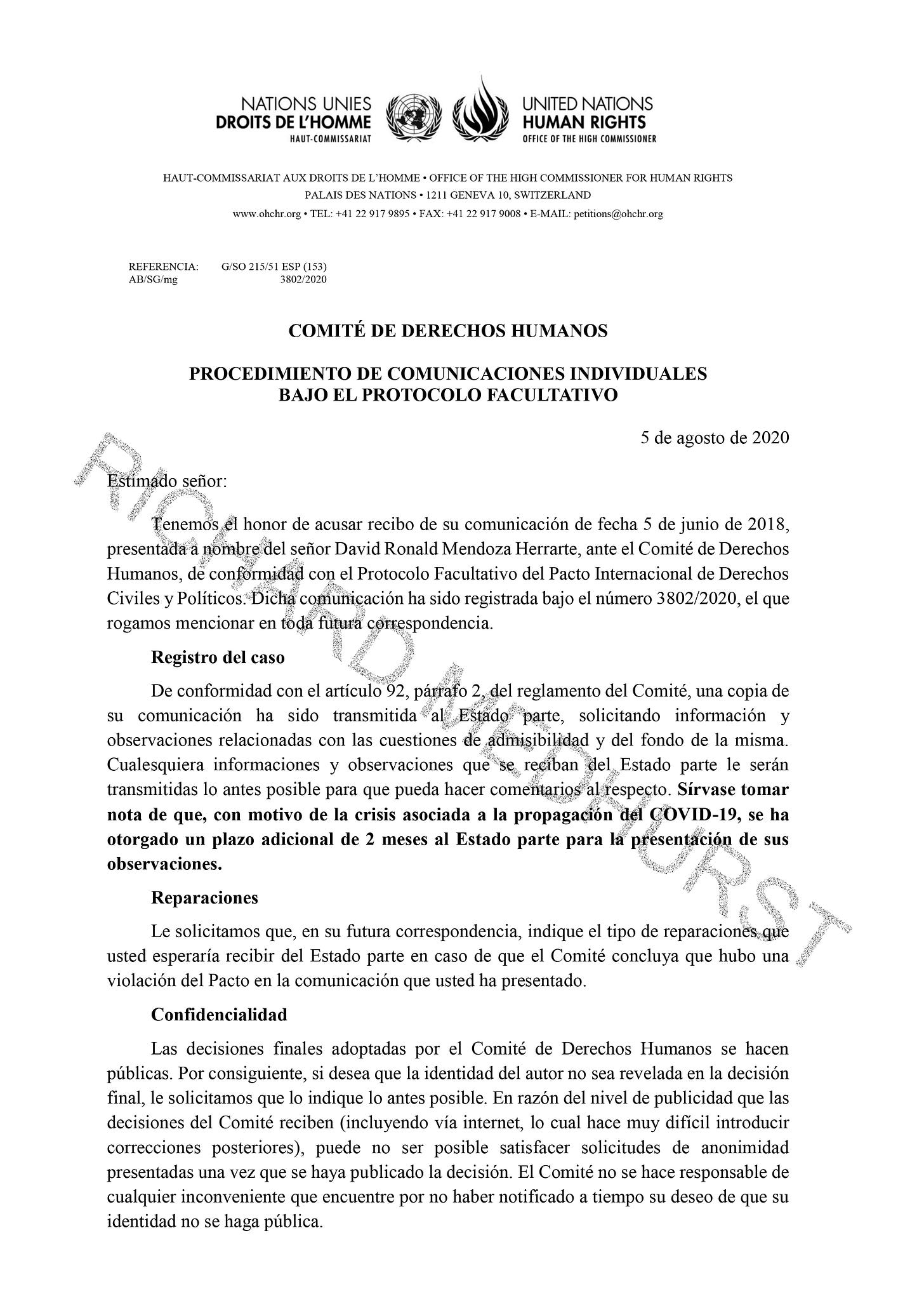

In 2020, Mendoza filed a complaint against Spain at the United Nations for sentencing him to prison retroactively. Usually, the UN only accepts 1-2% of cases brought before it. They took his.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is an international treaty meant to protect civil and political rights; a treaty which Spain is a party to. Ex post facto criminalization, i.e., implementing a criminal law retrospectively is prohibited under the treaty.

I asked Mendoza what a favorable ruling from the UN would look like. “We asked that the United Nations forces compensation, publish my case in three major newspapers, and change the law to be effective.”

Spanish prosecutors told the United Nations that Mendoza’s complaint should be denied. They allege the only reason he came back to Spain was to get a sentence reduction. (In Spain, Mendoza would have received 6 years instead of the 14 years the United States gave him, for the same crime).

Mendoza says their claim is ridiculous. “Who imposed my return to Spain? Me or the courts? The courts, obviously, so go and try telling them that they’re ‘abusing’ the law.”

The Spanish government came to Mendoza’s attorney and asked if he’d be willing to drop the UN suit. They asked if it was a question of money. Mendoza says: “I told them to fuck off. I don’t want money; I’m not dropping this suit. I want this thing to be established as law, or it’ll be the same old dirty system.”

Mendoza hopes the United Nations will rule in his favor, a process which can typically take around 2 years.

Despite the United Nations taking his case, Mendoza has been deeply affected by the extradition, the numerous legal battles and abuse of his human rights.

While in prison, both his parents passed away. “I lost my parents after five years in federal prison. I was deprived of hugging my mother as she suffered through pancreatic cancer,” he recalls. The relationship with his ex-wife and children has also been strained.

“I blew my whole inheritance, and every honest dollar I ever made on this case. If I didn’t have these resources, I would still be in US prison.”

The United States government took $14 million from Mendoza, seizing various assets, restaurants and properties, the vast majority unrelated to marijuana. I asked Mendoza roughly how much he spent on legal fees trying to get back to Spain. He estimates somewhere between $220,000 – 250,000. He says he’s lucky compared to others. Had he no money to spend on lawyers, he would still be stuck in an American jail.

“I feel really bad about those guys still in prison, kids given life sentences for marijuana. It’s legal nowadays in most states in the US, yet they’re still in jail. You got a president whose son smokes crack cocaine, if he were anyone else, he would have gotten at least a 5-year sentence. Why shouldn’t everyone get a fair shot like him? It’s disgusting how the public turns a blind eye.”

Mendoza accepts that he did the crime, however, he says: “If the law has to apply to the letter for me, why doesn’t it for the United States government? The United States made a deal with Spain to send me back, and it broke that deal.”

Mendoza has offered his help to others facing extradition to the United States, including the late John McAfee, infamous arms dealer Viktor Bout, Konstantin Yaroshenko.

In 2013, a French court blocked the extradition of Michael and Linda Mastro to the United States, citing Mendoza’s case as proof that France could not trust assurances from the United States.

Mendoza hopes that his case will also help Julian Assange, who faces up to 175 years imprisonment in the US for publishing diplomatic cables and evidence of US war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan. The indictment against him effectively criminalizes journalism.

I covered Assange’s High Court appeal last month. The US is attempting to extradite him from the United Kingdom to the United States. Similarly, the US offered diplomatic assurances that Assange could serve his sentence in his home country of Australia.

I told Mendoza what James Lewis, the lead prosecutor, had said: “The United States have never broken a diplomatic assurance, ever.”

Mendoza exclaimed: “That response from the prosecutor? Honestly, I don’t frequently lose sleep but that’s disgusting, just to hear that from someone who’s supposed to tell the truth to the court.”

Assange’s lawyers cited Mendoza’s case as an example of the United States breaking its diplomatic assurances, suggesting that the ones being offered now for Assange cannot be trusted. Lewis replied that the United States didn’t break its assurances because in the end Mendoza was allowed to return to Spain to serve his sentence.

Mendoza was angered by Lewis’ response. “That’s like giving someone a death sentence, they manage to appeal it, and then you say you didn’t try to kill them. They put every impediment they possibly could [to stop me from going back to Spain].”

The other assurance offered by the United States appears to state that Assange would not be jailed at ADX Florence or placed under oppressive prison conditions known as Special Administrative Measures (SAMs).

Similiar to those offered for Mendoza, the assurances for Assange are ambiguous and vaguely-worded. The United States says he will not be subject to SAMs or imprisoned at ADX unless “in the event that, after entry of this assurance, he was to commit any future act that met the test for the imposition of a SAM pursuant to 28 C.F.R. § 501.2 or § 501.3.”

Once in US custody, the United States could simply allege that Assange did something that “met the test for the imposition of a SAM,” place him in isolation, and then claim that it never violated its assurances, because it already gave itself a backdoor to do so.

This is why Mendoza told me that assurances must be explicitly spelled out, with no room for derogation.

Assange’s extradition was blocked by a UK judge in January 2021, on grounds that US prison conditions would be too oppressive, leading him to commit suicide.

While in the US, Mendoza was imprisoned at a medium-high security facility in Englewood, Colorado. This is near ADX Florence, where Assange is likely to be sent.

“Believe me, European prisons aren’t nice. But US prisons are much worse. I was in Colorado, one of the biggest shitholes I’ve ever been to. It was dirty; they let you out of your cell one hour a day—when they decided, not when I wanted.”

“The prison cells had TVs that would randomly come on. If you asked the guards to change the channel too many times, they would punish you. It’s 3am, for example, they would buzz you and say: do you want your hour of recreation? Prisoners who declined would not be able to leave their cell until the next day.”

Mendoza explained to me the process of dehumanization and sleep deprivation in prison: “You don’t have a name; you have a number, and you have to repeat it during every count. Counts are every three hours in higher security federal prisons. Another thing guards would do is instead of pointing their flashlight up to the ceiling, they would flash it right in your face.”

“I’m scared that will be Assange. They will make him go nuts. The only thing that kept me sane is this legal work; writing to the judges and the press, going after the United States in civil court.”

What Mendoza went through is a step down from what Assange would be in. Not only is ADX Florence a federal super-maximum prison, but Assange would also be placed under Special Administrative Measures (SAMs), in extreme isolation.

Mendoza tells me that visitation had to be approved by specific people. “My wife was Canadian, but I had to get permission for her to cross the border every time she came to see me, because they thought I was passing on communications through her. I had to go to court just so my wife could bring my children to see me.”

At the time, Mendoza’s parents lived in Seattle, WA. He asked for a transfer to a facility in Sheridan, Oregon so he could be closer to them. “They sent me to New Jersey instead [on the other side of the US], to spite me.”

The whole point of Mendoza serving his sentence in Spain was that he could be close to his loved ones. Hence why such a condition was imposed by the Spanish Court: to maintain the nucleus of the family.

Under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, every prisoner has the right to respect for private and family life. This means that they cannot be imprisoned in a place that is so far away as to make family visits difficult or impossible.

Despite sending Mendoza back, in the end the United States succeeded in violating the whole point of this condition: Mendoza’s family fell apart. While in prison he lost his parents, he and his wife divorced, and he tells me, “My children don’t call me ‘dad,’ they call me David.”

Mendoza’s case is an incredible story on its own merits.

Nevertheless, it must be examined in the context of Assange’s extradition. When James Lewis told High Court judges that “the United States have never broken a diplomatic assurance, ever”—this is simply untrue.

The above documents make it clear that the United States violated its agreement and broke diplomatic assurances to Spain. Mendoza was to be returned to Spain to carry out his sentence, instead he spent six years and nine months in various US prisons. Only after suing both the United States and Spain—his own countries—for failing to enforce the conditions of his extradition, was he allowed to return. Only after the Spanish Supreme Court ruled in his favor, threatening the US-Spain Extradition Treaty itself, could he compel the United States to enforce the conditions of his extradition and return him to Spain.

Mendoza was fortunate enough to have the Spanish Supreme Court, senior judges and public on his side. Were the United States to violate the assurances of Assange’s extradition, it is extremely unlikely given the “Special Relationship” between the UK and US, that Assange would be able to successfully lobby the British government into compelling the US to uphold the conditions of his extradition.

James Lewis told the English High Court that diplomatic assurances are “solemn undertakings, given out at the highest order; they are not dished out like smarties.” He is correct. It is therefore incumbent on the Court to consider what happened to Mendoza, for whom the United States did offer diplomatic assurances, and assess whether those offered for Assange are adequate, but more importantly, whether they can be enforced once he is no longer under British jurisdiction.

Mendoza’s experience shows that for Assange, any diplomatic assurances or agreements must be written in explicit language and signed by all parties, including Assange, so that in the eventuality of non-compliance, he may be afforded the opportunity to contest this in court, despite his status as a non-signatory of the United Kingdom-United States Extradition Treaty.

Mendoza’s case offers the Court extraordinary insight into the inner workings of American diplomacy, legal proceedings, and extradition to the United States. It is a serious warning which High Court Justices should heed, who at their discretion, have the power to prevent gross miscarriages of justice which gravely imperil the respondent, before they arise.

“I’m a nobody. If they’re capable of doing this to me, just imagine what they can do to Assange,” Mendoza warns.

Richard Medhurst is a Syrian-British journalist, a producer and host of the PressTV show Communiqué, and contributor to RT. He also hosts his own show on YouTube where he speaks on geopolitical issues regarding the Middle East, US foreign policy, and world affairs.

Featured image: US government’s diplomatic assurances for Julian Assange are meaningless, as similar assurances were broken many times by the US, including in the case of Spanish national David Mendoza. Photo: Richard Medhurst

(Substack)