If sanctions can be invoked by a social media network to take down certain content, what is next?

By Ari Paul

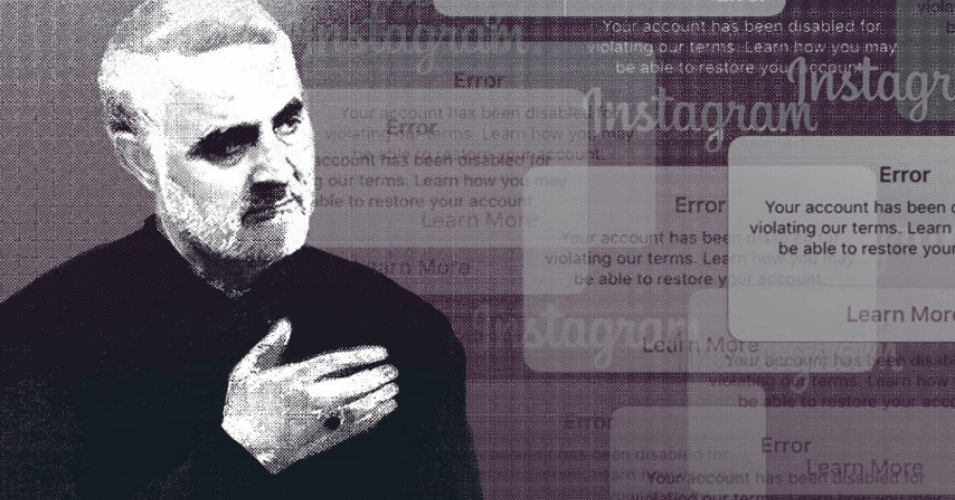

Instagram, and its parent company Facebook, took down posts regarded as too sympathetic to Iranian Gen. Qassem Soleimani, who was assassinated January 3 in a controversial US airstrike. The news website Coda (1/10/20) was credited with breaking the news, and Newsweek (1/10/20) also reported that:

Iranian journalists have reported the censorship of their Instagram accounts. Posts about Soleimani have disappeared from Instagram, which is currently the only operational international social media site within Iran.

According to the Facebook corporation, as quoted by CNN (1/10/20), removal of such posts is required by US sanctions; the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, of which Soleimani was a commander, was designated as a terrorist organization by the US government in April:

As part of its compliance with US law, the Facebook spokesperson said the company removes accounts run by or on behalf of sanctioned people and organizations.

One might rightly ask: What constitutes a post supportive of the late military commander? According to the CNN report, merely posting a photo of the general could get the Facebook authorities to take a post down.

RELATED CONTENT: Killing Soleimani Broke International Law: Former Nuremburg War Crimes Prosecutor

The International Federation of Journalists condemned the censorship:

The measures have gone even further, and some accounts of Iranian newspapers and news agencies have now been removed from the social media platform. This poses an immediate threat to freedom of information in Iran, as Instagram is the only international social media platform currently still operating in the country.

The Washington Times (1/11/20) reported:

Ali Rabiei, a spokesperson for the Iranian government, complained from his Twitter account on Monday this week about the disappearance of social media discussions about Soleimani, accusing Instagram of acting “undemocratic and unashamed.”

Much of the coverage has centered on the fact that Instagram is one of the few social media networks not widely restricted in Iran—thus, the blackout serves as a way of censoring information going into Iran. In fact, the US government news agency Voice of America (1/7/20) reported that the Iranian government was clamping down on social media posts too critical of Soleimani, and NBC News (8/21/19) reported on how Iranians used networks like Instagram to skirt government regulation. (The irony here is thick.)

But this news has also gotten journalists and press advocates worried about what this means for free speech and the First Amendment in the United States. On the one hand, as a private company, Facebook is free to make its own rules about acceptable content. Yet if the network is removing content because it believes it is required to do so by law, that is government censorship—and forbidden by the Constitution’s guarantee of freedom of the press.

Shayana Kadidal, a senior managing attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights, told FAIR that while it was possible for the US government to restrict media companies from coordinating with sanctioned entities and providing “material support” to the IRGC, the US government cannot restrict Americans from engaging in what he called “independent advocacy.”

RELATED CONTENT: Soleimani Killing: The Unintended Consequences

“Independent advocacy, as the law stands, can’t be banned,” he said. “For [Instagram] to remove every single post would mean it was pulling posts that are protected.”

The Washington Post (1/13/20) reported that free speech advocates were worried, with the director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation calling it “legally wrong.” Others concurred:

Eliza Campbell, associate director at the Cyber Program at the Middle East Institute in Washington, DC, [said] that the existing laws had failed to keep up with online speech, calling it a field of law “that hasn’t been written quite yet.”

“The terrorist designation system is an important tool, but it’s also a blunt instrument,” she said. “I think we’re walking down a dangerous path when we afford these platforms—which are private entities, have no oversight, and are not elected bodies—to essentially dictate policy, which is what’s happening right now.”

Emerson T. Brooking, a resident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, [said] that Facebook and Instagram are taking “a very aggressive position and it may not be sustainable.” He said it could result in Facebook removing any speech of any Iranian mourning Soleimani’s death and could represent a “harsh new precedent.”

Regardless of whether the government directed Facebook to take this action, the fact that a media company felt the need to do so is proof of a chilling effect on speech. Who, specifically, is to decide what is so unabashedly pro-Soleimani material that it violates US sanctions? Is an article that merely acknowledges that many Iranians mourned Soleimani and denounced his killing a violation? Is an anti-war editorial that doesn’t sufficiently assert Soleimani was “no angel” constitute such a crime? Could satirical material that facetiously supported the Tehran regime get censored? (The last item isn’t so hypothetical: A Babson College professor was fired for jokingly encouraging Iran to follow Trump’s lead by targeting US cultural sites.)

All of these questions, and all this ambiguity, should be enough evidence that this kind of censorship would be capricious and unfairly applied, and thus inappropriate in the face of free speech protections.

Free press advocates in the United States should think seriously in the coming days about how to respond. If sanctions can be invoked by a social media network to take down certain content, what is next? In order not to find out, we’ll need a concerted pushback to Facebook’s censorship from journalists and civil libertarians.

Ari Paul is a New York-based journalist who has reported for the Nation, the Guardian, the Forward, the Brooklyn Rail, Vice News, In These Times, Jacobin and many other outlets. Follow him on Twitter: @aripaul

Featured image: According to the CNN report, merely posting a photo of the general could get the Facebook authorities to take a post down. (Photo: Coda/Screenshot)

- orinocotribunehttps://orinocotribune.com/author/orinocotribune/

- orinocotribunehttps://orinocotribune.com/author/orinocotribune/

- orinocotribunehttps://orinocotribune.com/author/orinocotribune/

- orinocotribunehttps://orinocotribune.com/author/orinocotribune/April 24, 2024

Tags: corporate censorship Facebook first amendment Freedom of press freedom of speech General Qassem Soleimani Instagram Iran Social Media US Imperialism

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)