Peru: Community Kitchens, Crisis and Inequality

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

By Marco Teruggi – Jun 30, 2021

The pandemic and the economic crisis in Peru have led to the emergence of community kitchens being organized in the poorest areas of the country’s capital, Lima. In such neighborhoods, local women have organized themselves to get food and cook it, thus facing poverty and filling in for the absence of aid from the State.

It is noon and Edith Tajani comes to the door of her house with a megaphone in hand. ”Neighbors, lunch is ready, you can come and collect,” she speaks into the megaphone. Tajani is surrounded by hills on which there are a few scattered brick houses, and many more houses made of wood, cardboard and other materials that can be scavenged in one of the poorest and most populated areas in the south of Lima, Villa María del Triunfo.

Beside Edith stand the women who have prepared the collective meal. The menu for this day is rice, lentils and tuna fish. Women and children begin to approach with bags, plates and different containers to take home their lunch. The women who manage the kitchen keep note of the names of each person in a list that is upgraded daily at the Community Kitchen Juntos Venceremos esta Lucha [Together We Will Win This Fight].

Queue for food outside the community kitchen Juntos Venceremos esta Lucha. Photo: Sputnik / Marco Teruggi

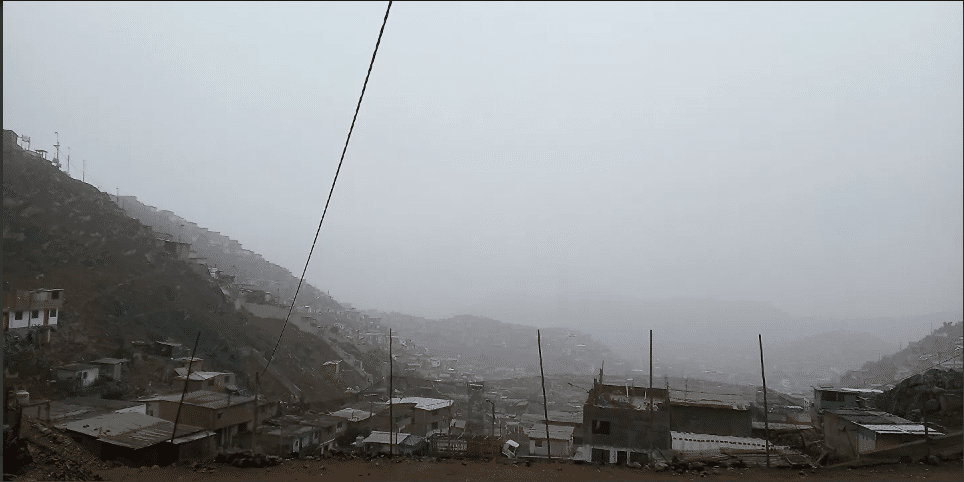

Queue for food outside the community kitchen Juntos Venceremos esta Lucha. Photo: Sputnik / Marco TeruggiIf it weren’t for the clouds, one would have been able to see the entire extent of the immense working class neighborhood that is a succession of conic hills filled with houses up to their tops. But this is the season of permanent clouds, of rain, cold temperatures, and danger for those who live here. A neighbor approaches Edith and tells her that her house fell down due to the rain, the mud, and poverty. She carries her daughter on her back wrapped in a lliclla, a traditional colored cloth of the Andes.

RELATED CONTENT: Perú: Fujimori’s Right-Wing Thugs Kill Castillo Supporter in Clashes

Edith was part of a group that started the kitchen at the beginning of the pandemic. ”The lockdown order was imposed, and everyone was left without work. We had to stay with the family at home,” she recalls. The store where Edith was employed in Lima closed, and her two daughters could not continue their work of going to Brazil to sell clothes. The three women were left without a fixed income and with the responsibility of supporting ten grandchildren.

Edith says that the kitchen started with a donation of thirty chickens. ”Then each family brought rice, peas and we made a large pot of food,” she recalls. ”We began to distribute food to everyone and started to call the neighbors.” The formation of the olla común [community kitchen] in her locality, Las Flores del Paraíso, coincided with the multiplication of kitchens in poor neighborhoods. Edith is now in charge of coordinating 80 kitchens in her area. It is estimated that there are around 2,700 kitchens in all of Lima and about 243,000 people who depend on them for food.

Against all odds

View from the community kitchen Santuario de las Vizcachas. Photo: Sputnik / Marco Teruggi

View from the community kitchen Santuario de las Vizcachas. Photo: Sputnik / Marco TeruggiAccording to María, who runs another community kitchen called Santuario de las Vizcachas, ”the government does not help at all. We collect money every day in order to be able to sustain our kitchen; otherwise there would be no food; we would not have anything to eat. What we want is that there should be a budget for the community kitchen, to be able to sustain it every day.”Here also the lunch is rice, with lentils and squash porridge. The women cook with gas and firewood, and, as there is no water supply here, each neighbor who buys their lunch at the price of 2 Peruvian soles (around $0.60 US cents) brings with them a bucket of water. The kitchen is at the foot of a hill that, higher up, is beginning to turn green with the first yellow amancay flowers. Up there, on the slope of the mountain are the houses at the highest reaches, built of wood, and without electricity.

Lack of state support is a common feature in the different kitchens that Edith coordinates. ”We want support for all the community kitchens; we are all suffering,” says Lurdes Canchari Santos, who cooks at the Santuario de las Vizcachas kitchen. ”In each kitchen we strive from day to day to feed people in need, our elderly, our children.”The situation has not really changed from the beginning, when the kitchens were spontaneously born out of necessity in the face of the pandemic and the economic crisis, which hit an economy where 70% of the population is engaged in some form of informal work. In the case of the Las Flores del Paraíso kitchen, Edith and several women began to walk in the markets ”from stall to stall” asking for food donations.

More than a year later, the situation remains the same. Help from the government has been scarce and not generalized, remarks Edith. ”The only thing that we have received from the government, just twice during the entire pandemic, are some baskets with small packages of sugar, noodles and beans. That is what the government has sent us. We do not have government; the only aid that comes to us is what we go out to seek in the factories, from the NGOs, in the parish.”

”We have asked that they declare a food emergency, a permanent budget and that common kitchens be legally recognized as an organization by the State,” explains Edith. ”We have also asked for technical training to carry on with our organization.” Today, the situation is the same as at the beginning: these women have to rely solely on their own initiative, will and perseverance.

Hope for change

Edith, on the right, at the Santuario de las Vizcachas community kitchen. Photo: Sputnik / Marco Teruggi

Edith, on the right, at the Santuario de las Vizcachas community kitchen. Photo: Sputnik / Marco Teruggi”A number of people from different political parties have come here to look for me during elections,” says Edith. This was the case for different community kitchens as well. ”During the campaign the people from the kitchens would call me up and tell me: ‘Look, a man came saying that he can monetarily help, but he wants us to put up a political party banner.’ I would tell them to receive the help if they want to give it, but not to put up the party banner, because the day the campaign ends they will forget about us.”

In the first round of the presidential elections, Edith voted for Verónika Mendoza, the progressive candidate of Juntos por el Perú, who came in at the sixth place in the April 11 elections. ”She is a feisty and provincial woman like us, the heads of the community kitchens,” Edith explains.

Then, on June 6, Edith and the others decided to vote for Peru Libre’s Pedro Castillo, ”because he too is from the provinces. We hope that he will be with us, with his people, and that he will understand his people’s needs, and that we need him as president. We hope that the professor brings a total change and ends all that corruption that is in the country.”

RELATED CONTENT: The Imminent Coup in Peru

The provincial component, that is, those who are not from Lima, is important in Edith’s area, where the vast majority of people come from the different provinces within the country. In Edith’s case, she came ”from the jungle,” as it is said, from the Loreto department, on the border with Colombia. Her kitchen companions are from Ayacucho, Puno, Arequipa and other places.

Edith and the community kitchens are part of the deeply unequal social geography of Lima, in a country crisscrossed by multiple fractures. These cleavages are quite visible—on the border between Villa María del Triunfo and La Molina, one of the richest areas of the capital, there is a partition called the Wall of Shame, which is a wall running several kilometers that prevents passage from one side to the other.

These divisions within Peruvian society were also visible in the June 6 election in which Castillo and Keiko Fujimori, of the neoliberal and dictatorial right, faced each other. The Peru Libre candidate brought together under him a range of demands, expectations and the need to ”start over,” as Edith states. Although he could not win in any electoral district of Lima, the support that he got in the provinces allowed him to win the election with 44,058 more votes than his opponent.Although the political situation in the country is still unstable due to Fujimori’s attempt at not recognizing the results, Edith has expectations for Castillo’s future government, which should begin on July 28. ”The hope is that there will be a redistribution of wealth, which right now is in the hands of a tiny minority,” continues Edith. ”At the same time, the vast majority of people—look at how we live! Look at the hills that you have climbed up! We live without water, without electricity, without roads—this is the reality. We want decent housing, decent food, a minimum wage. We don’t want them to give us anything for free, we want work,” she concludes.

Featured image: A community kitchen in the impoverished areas hard hit by the pandemic and the economic crisis in Lima, Peru. Photo: Sputnik / Marco Teruggi

Argentinian Sociologist. He played in the Anahí Association, in HIJOS and in the Popular Front Darío Santillán. Since the beginning of 2013 he lives in Caracas. Author of the books: "I always return to the foot of the tree", "Founded days" and "Chronicles of communes, where Chávez lives". Currently collaborates in Telesur, Latin American Summary, Notes, Sudestada Magazine, Amphibian, among others.

You must be logged in to post a comment.