From Hyperinflation to Hyperdeflation of the Pockets: is a Salary Increase Coming?

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

By Luis Salas Rodríguez

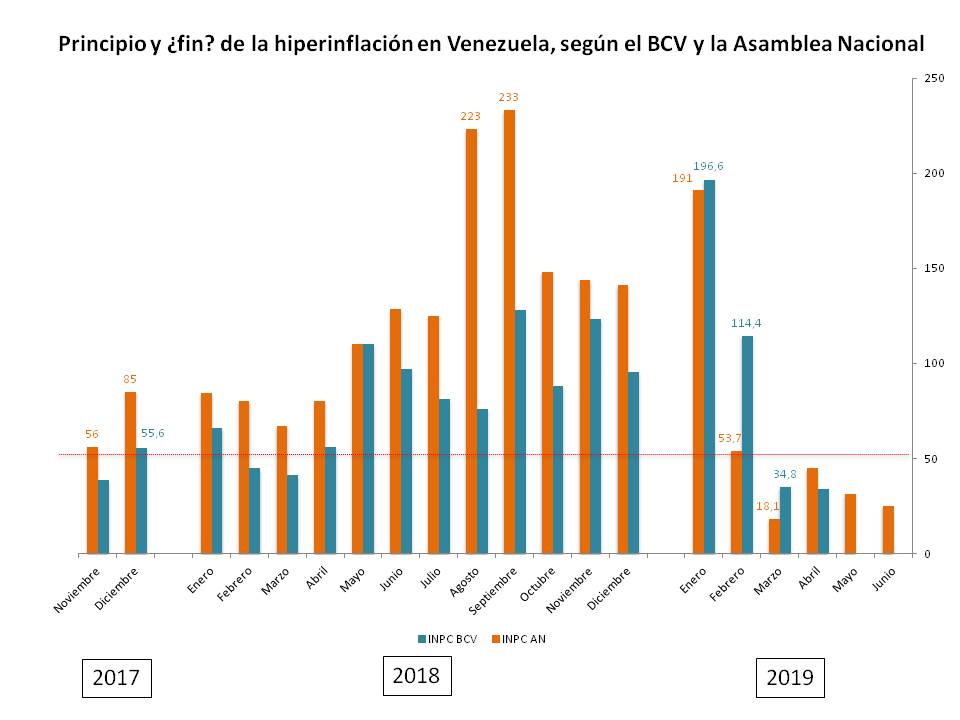

On April 11, a note was published here entitled “End of hyperinflation: good news?” regarding the INPC (national price index) reported previous days by the National Assembly, in that case the one corresponding to the month of March 2019 and which gave them 18.1%, less than half of the one reported by themselves for February (53.7%) and about ten times less than January (191.6%).

Our point then was that if the affirmation of the AN was true, it meant that, technically speaking, we were facing the end of the hyperinflationary rally this instance in contempt had been reporting unofficially since November 2017, on the understanding that, according to the conventions of economics, there is talk of hyperinflation when the National Consumer Price Index exceeds 50% monthly.

Given this, immediately the “experts” of anti-Chavismo jumped in arguing that it was not enough to have a month below 50% to talk about an end of hyperinflation. Of course, there was no shortage of mentions of Phillip Cagan, who is considered the main theoretician on hyperinflation, who in “The Monetary Dynamics of Inflation” (1956) points out that it ends “the month before the monthly increase in prices fall below that amount [50%] and remain below at least one year ”.

Our response was that the criteria in this regard are quite arbitrary, posing as episteme definitions that look more like dogma. In the case of the aforementioned author, in fact he points that out in passages of his work, but in other parts he does not put the tail end of that “necessary” year to decree the end of a hyperinflation, as well as not specifying why “a year” is necessary and not any other number of months. For the rest, other economists handle different criteria, including Steve Hanke, for whom Venezuela was in hyperinflation long before, at least since 2016. Or Carmen Reinhart, Miguel Savastano and Kenneth Rogoff, for whom a hyperinflationary phenomenon occurs when the rate reaches a year-on-year variation exceeding 500%.

To make good on the thesis of the arbitrariness of criteria, the deputy Ángel Alvarado, president of the Finance Commission of the AN and usually in charge of offering the parallel INPC that this instance in contempt does, said that “technically, going out of hyperinflation requires ( an INPC) three consecutive months below 50%”. This affirmation at the time seemed to give way to any government claim to sing early victory. However, from March to date, more than three months have passed and according to the AN, the INPC has only gone down further, so at this point under that criteria then, and unless they have changed it, Venezuelan hyperinflation finished last May.

Weeks after this debate, on May 28, the BCV ended three years of statistical blackout, proceeding to publish the economic indicators in question. And among the indicators published was the official INPC, which confirmed for the same month of March that the price growth rate fell below 50%. Unfortunately, the BCV has not updated numbers since then, being that the last INPC reported was that of April, also below 50%.

The most recent contribution to this debate was given in recent days by the Director of CENDAS, Oscar Mesa – openly oppositionist – who stated emphatically in an interview that hyperinflation in Venezuela had ended.

So: did it end or not?

Thus, if we take as reference the extra-official INPC published by the National Assembly and the official published by the BCV, we have that the evolution of the 2017-2019 Venezuelan hyperinflationary rally has been as follows:

As you can see, for the National Assembly hyperinflation began in November 2017 and was held for 16 consecutive months until February 2019. However, for the BCV it began a month later – December 2017 – in a series interrupted in February and March 2018, but resumed in April of that same year, also until February 2019. It will then remain open to discussion if the hyperinflationary rally for the BCV began strictu sensu in December 2017 until February 2019, or it is two series: a short one of two months and another long one from April 2018 to February 2019.

RELATED CONTENT: The Strength of Women: Venezuelan Commune Members Facing the Blockade

However this may be, the truth is that if we take as a reference the criteria of the Economy and Finance Commission of the opposition National Assembly, then the hyperinflationary stage, a criterion shared by CENDAS, also oppositionist, has already been overcome. This is not the case with Steve Hanke, for whom hyperinflation remains galloping although he acknowledges that its pace has decreased. The majority of opposition “experts” debate between this last position and those who say that although the fall in INPC growth below 50% per month is true, the causes of hyperinflation remain latent and at any time that rhythm will resume. Unfortunately, we do not know what the government and the BCV think, because upstream nobody speaks about it and consequently not downstream either.

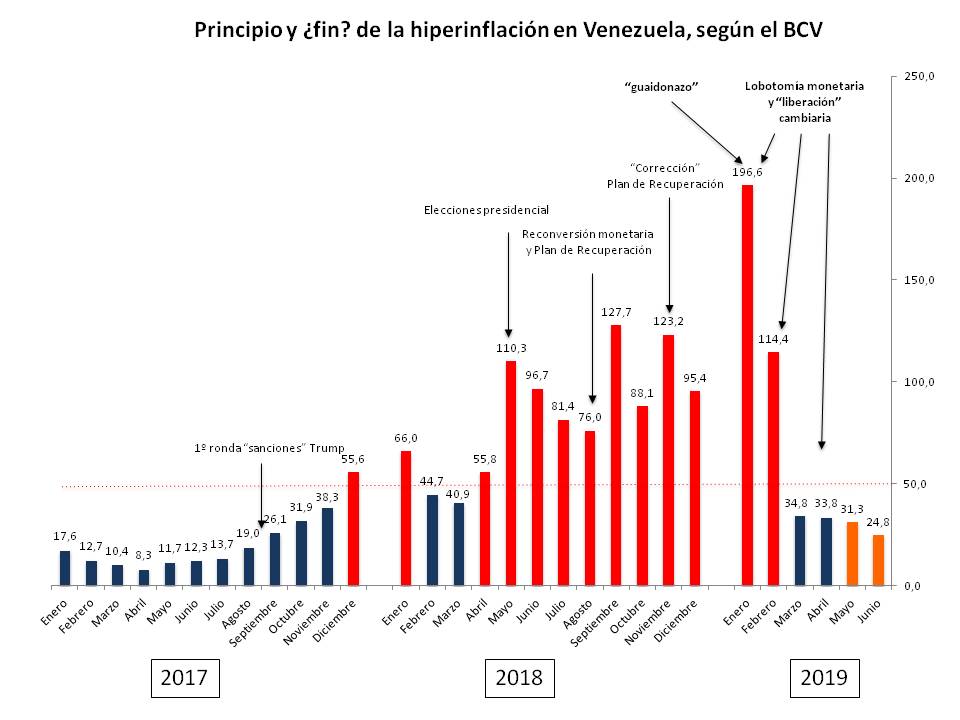

As far as this discussion is concerned, it is secondary, in the sense that more important than knowing whether the INPC will remain below 50% monthly or not, is to clearly understand the dynamics that made it possible to go from 196% in January 2019, to 34% only two months later, taking the official BCV figures as a reference. And what we are talking about here is the radical reversal of a trend that, by the smallest measure, lasted 11 months (again: according to the BCV), in the specific case of hyperinflation. The point is that something very decisive had to happen for that to happen, with the understanding that, from January to March 2019, the price variation fell 161 points, or what is the same: 5.6 times.

Once this is understood, we will be in a better position to answer what we can expect from now on, being one of many doubts to unravel if hyperinflation will return or if we can already consider it a thing of the past.

From hyperinflation of prices to hyperdeflation of the pockets: the resolution of the BCV trilemma

Let’s see the following graph:

In my view, the acceleration of the rate of price growth that degenerated in the hyperinflationary rally was mainly – not exclusively – from the shock wave caused by Trump’s first round of sanctions in August 2017, which generated sequels and added reinforcements throughout 2018. Subsequently, the rally reached a peak during the presidential elections of May 2018, gained a significant boost after the monetary reconversion and the Recovery Plan of August 2018 – in its first version – and November 2018, in its second “corrected” version.

In this regard, it could sound tempting to say that the rebound in hyperinflation from the August plan is paradoxical if it is considered that the announced purpose of said plan was to defeat it. However, reaching that conclusion seems superficial, to the extent that it involves a close reading of the anti-inflationary measures contemplated therein.

At first, the price rebound was predictable both due to the uncertainty of any measure of that nature – especially in the polarized context and our hysteresis – as well as the salary, monetary, exchange rate adjustments, etc., made in the framework of the conversion. Just to mention two, in addition to the injection of liquidity contemplated in said conversion, remember that in August the minimum wage was increased by 5,900%, while the exchange rate by 2,145%, equivalent to a devaluation of 95.5%, taking into account the previous values in Strong Bolivars (BsF).

Now, that was in the first moment of the plan. Of which it may be said (and under suspicion until further notice) that the hyperinflationary rebound was a side effect. But under no circumstances can the same be said of the second moment of the plan: in this case the rebound was deliberate.

And, as we reviewed widely at the time , it was from that November that the national government abandoned not only the agreed price policy ( apparently designed exactly to not work) but also and above all the publicized anchoring of the sovereign novel bolivar to the petro, splitting the latter into two (as a unit of account and as a speculative cryptoactive of “saving”) and anchoring both the bolivar and the cryptoactive petro to the dollar via DICOM. Since then, the exchange rate began to rise and the bolivar to be devalued rapidly as a result, since everything indicated that the economic policy strategy repeated what the government tried without much fruit since the second half of 2016: reach the exchange rate parallel and effect the definitive exchange “liberation” (remember in this respect that the law of illegal exchange was repealed in September ).

RELATED CONTENT: Venezuelan Food Houses: A Last Trench Against US Blockade

In our calculations , the above may have occurred between the end of 2018 and the beginning of 2019, around 800 sovereign bolivars. However, at the end of December, despite the devaluationist effort of the BCV, they failed to do so, and then the first week of January, while the DICOM auctions were on vacation, the parallel exchange rate began to increase dramatically. The fact is that when retaking the auctions the second week of January, the BCV was not intimidated by this behavior of the parallel and rather redoubled the bet, which led us to January 28, when after the “untimely” and “surprise” appearance of the private exchange platform Interbanex the exchange rate was set at 3,300 sovereign bolivars for US $, in a policy that the BCV termed briefly as “monetary anchoring.”

So that we have a clear idea of the magnitudes, we are talking about:

The application of this aggressive exchange rate policy in the middle of a conflictive political context, added to the seasonal factor of the time of the year (November-December are traditionally months of price increase) is what in principle explains the hyperinflationary rebound of the end of 2018. Said aggressiveness of the exchange rate policy in January 2019, but also the political conflict with everything associated with the “guaidonazo” , which in turn explains why two months like January and February when the INPC also for seasonal reasons is overall low, rather rose to its highest levels above, including, from September and August 2018.

Now: why does the INPC begin to recede from February and in fact falls below 50% in March, if the case is that in February we were at the brink of a military invasion and from January to date the aggressiveness of the Foreign exchange policy has not been lower (as of July 15, the official exchange rate was 7,246 VES per US $, more than double what it was at the end of January)?

The answer to this question is that in addition to the above and in the midst of the conflict that consumed us the first quarter of this year, the monetary authorities began to apply what we called monetary lobotomy at the time, that is, an aggressive policy of restricting all circulation of bolivars to the minimum possible (from August to date, in real terms the amount of money in circulation has fallen by 70%). To this end, it has been applying severe banking reserve measures, cutting almost any possibility for banks to issue their own liquidity through bank credit. However, the corrosive effects of the sharp devaluations on purchasing power, the de facto release of prices, budgetary cuts in the public sector and the deliberate wage lag policy (to a lesser extent a indirect layoff) that were combined to strangle, when not cut from the base, the monetary and merchandise flows through which hyperinflation was spreading.

The price to pay for this is that by strangling these flows, families and consumers in general were also strangled, including the State’s ability to buy and by that means the economy as a whole. That is why we call it a monetary lobotomy: because, as with the medical lobotomy (an atavistic and wild procedure, fortunately already unincorporated), everything indicates that the government opted to put an end to the price schizophrenia, plunging the patient into a state of catatonic prostration, a more dangerous condition insofar as it’s a matter of a country that has come through 5 consecutive years of historical contraction of its GDP (52% according to BCV itself between 2014 and the third quarter of 2018) involved in a complex political conflict and also severely blocked and harassed internationally.

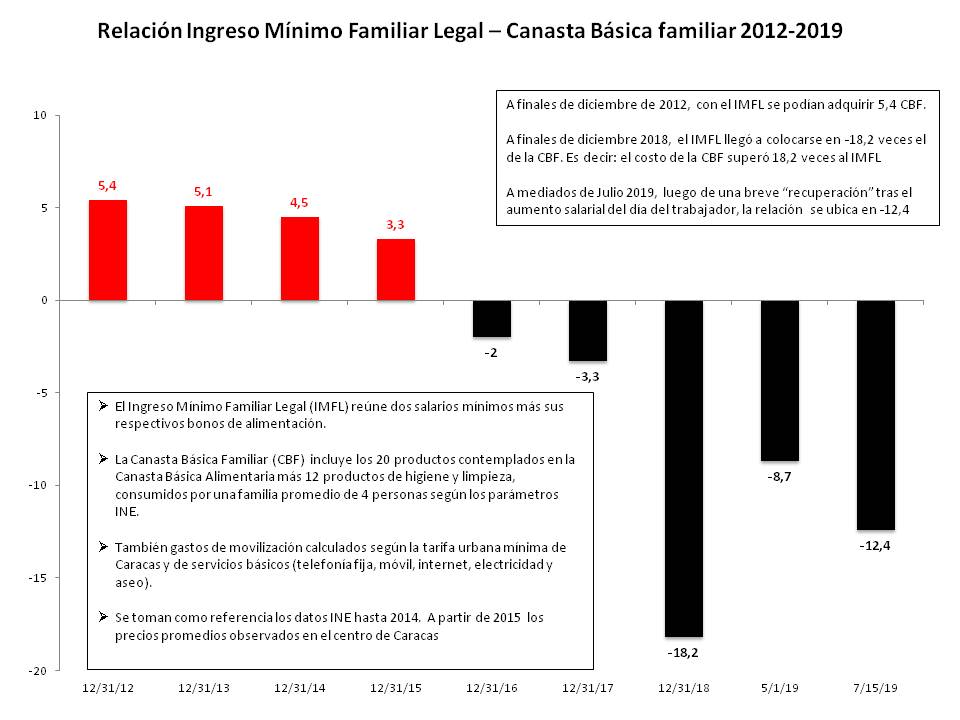

The demonstration of the above can be seen in the following graphs, where the dramatic fall in purchasing power is represented. Or what is the same: the replacement of hyperinflation prices with hyperdeflation of the pockets.

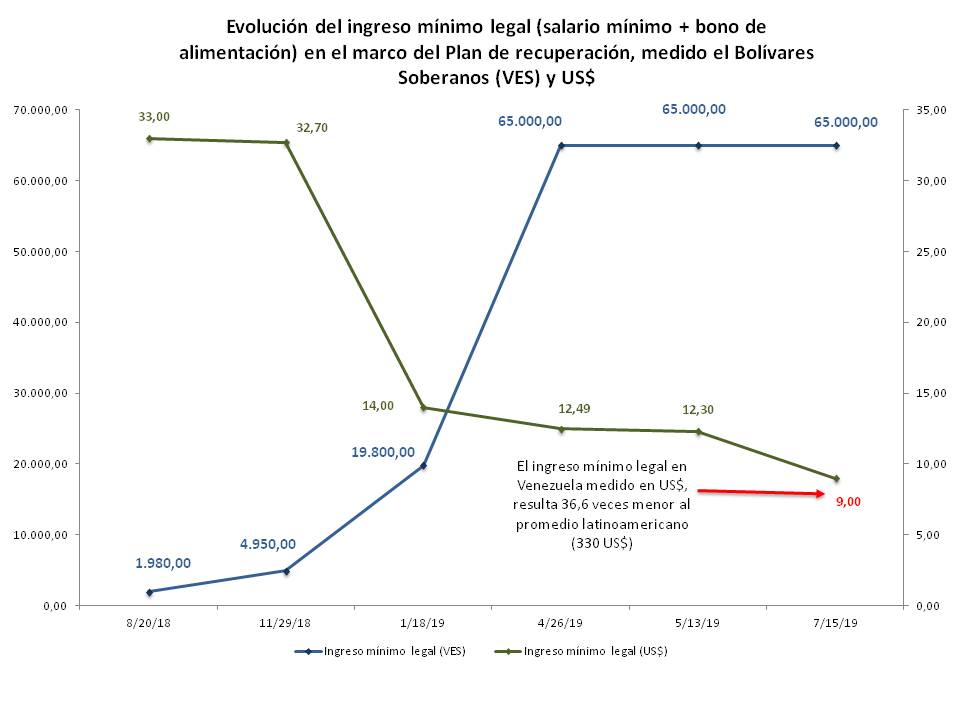

Or in this case, which reflects the dramatic drop in the minimum wage in both bolivars and dollars:

As we pointed out at the time, the trilemma of goals presented by the BCV (stabilizing the exchange rate, stopping hyperinflation and regaining purchasing power) was impossible given its jump to the neoliberal side of wild monetarism. In any case, it could precariously achieve the first two, but at the expense of the third, that is, sacrificing purchasing power even more: and thus exactly broke the wave.

Rumors have circulated in recent days about an alleged salary increase by the end of this month or August. We think that August makes more sense, in the spirit of the “celebration” of the first year of the “Recovery Plan”, however, given all the above, we do not see this possibility as clearly.

The problem is that from the political point of view (and we assume that ethically) the government feels the pressure to increase, since it is aware that the current levels of purchasing power are unsustainable for the majority and constitute a time bomb. Now, it is also aware that it will be putting increasing pressure on prices, and their precarious pax in the exchange rate could end and behind it, hyperinflation will be back.

The issue here is that the government got into a trap by itself, which in May it was able to escape, partly helped – who was going to say it – by Guaidó: and we remember that given the May Day it was forced to raise the salary , but not only did it well below expectation, but previously incurred in monetary and exchange juggling so that inflation was not triggered again. The result was that it increased the salary (nominally) without increasing almost anything in real terms, and the little increase in real terms was immediately eaten by the price adjustment that occurred at the same time but not in the same dimensions as before. Guaidó’s help to this cause was the Coup attempt of April 30, since it saved the government the job of explaining all the juggling.

Moreover, it should be noted that the pax exchange rate may already be running low: The parallel exchange rate is increasing significantly, to the point that the gap between one and the other is widening and for today, July 17, 2019, it is already around 40%, since the parallel is already exceeding the 10 thousand sovereign barrier. In this increase several factors must be influencing: from the pure and hard manipulation given the deflation of the “guaidonate” and to put pressure on Barbados, until the end of the honeymoon of the interbank tables, through the relative increase of the expenditure on bolivars in the last weeks by the State. It is also not ruled out that it is a previous movement anticipating the salary increase. But you also have to take into account that the increase in costs in bolivars has eroded the dollar’s purchasing power.

From my point of view, no matter how true the above is and something else that escapes me, in reality, the available supply of dollars must also be lowering because its holders have less incentives to sell them, firstly because as we have been warning for some time, it has been consolidating a “parallel” liquidity in dollars and currencies in general that makes it unnecessary to exchange dollars for bolivars, to the extent that it is increasingly possible to pay directly with dollars.

In this sense, it must be understood that the dollar holders had two basic motivations to change them to bolivars so far: either because they needed bolivars to make a specific payment, or because they made the return to sell dollars in exchange for bolivars to buy dollars again by betting at higher future prices and get the differential. To the extent that you can already pay almost everything with dollars the need to have bolivars decreases. But also having slowed in the growth rate of the exchange rate, selling dollars to obtain bolivars to buy dollars that can be sold more expensively makes no sense. That added to the inflation in bolivars that grew more in recent weeks than the devaluation already noted about remittances, restricts the supply of dollars and therefore makes them more expensive.

However, it is expected that this will end up moving to the prices of goods and services, as is already happening.

Last but not least: when the payment is consolidated directly in dollars to the point that as we have been saying there is already an additional liquidity in currencies independent of that of bolivars, the incentives to exchange those for these are increasingly smaller, which translates into a decrease in the supply of the former while their demand grows, which then makes them more expensive. Of course, this will also end up putting pressure on the (hyper) inflationary pot, to the detriment of those who still live in VES (Bolivars), who are the vast majority of Venezuelans.

Anyway, whether or not the government increases the salary in the next few days will depend on several factors. In my view, I would rather not have to do so, privileging keeping hyperinflation at bay. But politically speaking the pressure is in the opposite direction. In that sense, most likely, if you do so by repeating the juggling of May, looking at all costs to close the year with an average monthly inflation that does not exceed 35-40%, which would place it between 20 and 25 thousand% at the end of the year. This is certainly still a lot, but quite far from 130 thousand% of 2018. It would be an achievement. But at the cost of the great sacrifice of contracting the economy more and keeping purchasing power as low as possible, as if it were an internal blockade that adds to the external one.

Translated by JRE/EF

You must be logged in to post a comment.