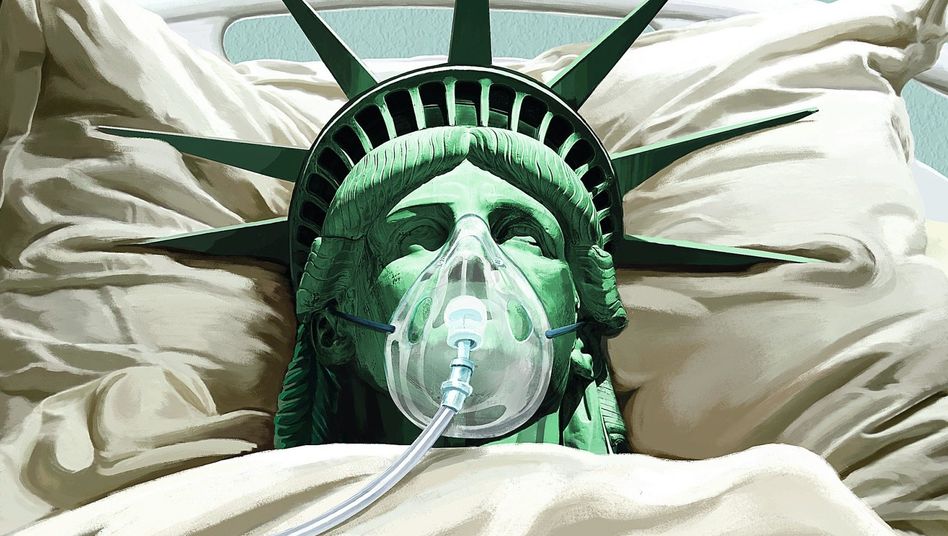

Donald Trump’s disastrous crisis management has made the United States the new epicenter of the global coronavirus pandemic. The country is facing an unprecedented economic crash. Are we witnessing the implosion of a superpower?

By Kerstin Kullmann, Guido Mingels, Ralf Neukirch, Philipp Oehmke, René Pfister, Marc Pitzke und Michael Sauga

“I never would have thought I would ever have to do something like this,” Greg Turner says with a bitter smile, as if he feels he has to apologize. It’s a rainy gray Monday afternoon in Alameda, California. Turner, 55, who sports a beard and a cap, is one of dozens of Americans who have lined up to enter the city’s food bank. When asked if he has lost his job, he runs his hand, held parallel, across his throat. He was laid off without any notice three weeks ago after working for 15 years as a machinist at a supplier for DowDuPoint Inc., the chemical industry giant.

“There are 10 times more people coming than usual,” says Cindy Houts, the food bank’s executive director, “and there are more coming each day.” To cope with the onslaught, she has decided to move food distribution to an industrial zone on the outskirts of town. The line stretches out over two blocks. Everything is done according to strict rules.

If a person arrives in a car, they are not allowed to lower their windows. When the driver reaches the stop mark, the engine has to be turned off and the trunk opened. Then three helpers with protective masks step up to the trunk, one after the other, and load three paper bags into it. One contains non-perishable foods, one contains dairy products, the third contains fruits and vegetables. Not a single word is exchanged. All you can hear is the sound of the rain pattering on the roofs of the cars.

Pictures from the 1930s

Nowhere is the coronavirus crisis as visible in the U.S. as at these food distribution centers. One Chicago food bank distributed over three tons of food in a single day. In Manhattan, the line for a soup kitchen extends for several blocks. If the scene were in black and white, one would have trouble distinguishing it from pictures from the 1930s.

When Donald Trump was sworn in as President three years ago, he pledged to give the nation pride and strength. “We will bring back our jobs,” Trump said in his inaugural address on Jan. 20, 2017. “We will bring back our wealth.” He even spoke of freeing the Earth from the “miseries of disease.” He said, “A new national pride will stir our souls, lift our sights, and heal our divisions.”

Now the coronavirus has plunged the country into the greatest crisis since the Great Depression. That period began with the crash of the New York Stock Exchange in the fall of 1929 and is still etched into the collective consciousness. The pandemic is affecting every nation on the planet, but nowhere in the Western world has it brought to light shortcomings as relentlessly as it has in the United States. At the end of February, the American president claimed that his government was in complete control of the situation. But now the number of infected is approaching the 500,000-mark. Hospitals in New York, Detroit and New Orleans are barely able to cope with the onslaught of sick people.

Die Lage: USA 2020Ihr wöchentliches Briefing zum Kampf ums Weiße Haus. Unsere US-Korrespondenten berichten für Sie jeden Mittwoch von vor Ort. Der Newsletter zum politischen Ereignis des Jahres.

And unlike in previous global crises, the U.S. is failing as a global leader. The country is currently too concerned with itself. Trump, as is so often the case, is trying to save himself by attacking the international organization that is supposed to coordinate the global fight against the crisis: the World Health Organization (WHO). He has threatened to defund the WHO because, he claims, it “blew it.”

During his inaugural speech in January 2017, Trump also said: “America will start winning again, winning like never before.” Now the U.S. has become the problem child in the global battle against the virus. While China and South Korea have stopped the spread of the contagion for the time being and parts of Europe are trying to slowly return to normality, the U.S. is setting one negative record after the other. No other country has as many infections, and the White House itself is predicting up to 240,000 deaths by fall. A study by the Federal Reserve Bank in St. Louis estimates that 47 million Americans will have lost their jobs by June.

Trump Played Crisis Down

The president played down and tried to suppress the crisis for months. He couldn’t decide whether to take the virus seriously or dismiss it as a pipe dream on the part of the Democratic Party. He seemed to view it as a ploy to keep him from getting re-elected.

Again and again, Trump’s advisers have had to bring him to his senses, but even that often doesn’t work. When the president announced a week ago Friday that the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) was going to recommend people wear masks in public, he immediately added that he wasn’t even considering wearing one himself. “I don’t see it for myself, I just don’t.” His comments certainly didn’t clear up any confusion.

RELATED CONTENT: Mass Graves in New York to Bury Covid-19 Deceased

But the pandemic is also exposing weaknesses that existed before Trump’s election: a health-care system that fails the very moment when it is most needed, and a capitalist system that is unrestrained during boom times, and unimpeded when it crashes. Above all, however, it has revealed a democracy that has forgotten how to compromise.

Is the world witnessing the collapse of a superpower? Is the U.S. facing a “Suez” moment, as Washington-based political scientist Rush Doshi puts it? In the fall of 1956, Egypt won the conflict over the Suez Canal, thus demonstrating to the world that the days of the British Empire were finally a relic of the past.

The end of the American era has often been evoked, but the signs of crisis have never been as clear as they are now. Although the virus began its spread at a market selling exotic animals in Wuhan, China has become the first country to contain the pandemic. It is now airlifting simple, but nevertheless scarce products to the U.S.: fever thermometers, masks and protective gowns.

A Shift in the Balance of Power?

The airlift from Shanghai to New York is a gesture of solidarity, but also a deft PR move. The image of Beijing providing relief to the U.S. the way it would to a developing country is intended to demonstrate the shift in the global balance of power: The American patient is being cared for by the strict, but kind Chinese doctor.

The Americans’ urgent need for help is most visible in New York, the country’s largest city, where hospitals are in danger of collapsing under the weight of the pandemic. “We are almost completely filled with coronavirus patients,” says Jonathan Marshall, the chair of the emergency medicine at Maimonides Hospital. It is Brooklyn’s largest hospital, with more than 700 beds. When Marshall calls by phone during a shift at the hospital, he sounds out of breath and is constantly interrupted by colleagues with questions. Marshall has worked nonstop since the start of the corona crisis in New York at the beginning of March.

Why is the disease hitting the city so hard?

When you speak to Marshall, it quickly becomes clear that what is most lacking is central coordination. According to a survey of its members by an association representing 42,000 New York nurses, around 85 percent have already come into contact with COVID patients, but almost three-quarters do not have access to sufficient protective clothing.

“We’ve had teams working around the clock for weeks now to source personal protective equipment,” says Marshall. He says he has tapped city, state and private resources. Has he obtained an assistance from Washington? “The Trump administration? No comment,” Marshall says. The hospital is currently spending several million dollars each month from its own funds to fight the pandemic. Marshall says it is still unclear whether the government will step in with aid.

The U.S. actually ought to be very well prepared for a pandemic. In 2018, almost 18 percent of the country’s gross domestic product flowed into the health sector, a total of $3.6 trillion (3.3 trillion euros). But the American health-care system is enormously expensive and highly inefficient. The wealthy and people with good jobs often receive excellent medical care. But a lot of that money goes into the coffers of pharmaceutical and insurance companies.

That is now being exacerbated by political ineptitude.

“It’s Going to Be Just Fine”

The first COVID-19 case in the U.S. was detected in Seattle on Jan. 30 – the same day South Korea had its first case. The South Koreans built up their own testing regime at break-neck speed and were soon able to test 10,000 suspected cases a day. Trump, on the other hand, claimed on Jan. 26 at the World Economic Forum in Davos, “We have it under control, it’s going to be just fine.”

Nothing could have been further from the truth. At the time, the CDC decided to develop its own test for the coronavirus rather than using a functioning one from the WHO. The test quickly turned out to be faulty, and as a result, weeks went by without anyone being able to determine how widely the disease had already spread in the U.S.

On Jan. 30, the WHO warned of a possible global coronavirus pandemic. The same day, at a campaign rally in Michigan, Trump said, “We’ve very little problem (sic) in this country at the moment.” In early February, some state governors began requesting help from Washington, mainly in the form of protective clothing and ventilators from the Strategic National Stockpile. The national reserve was set up in 1999, overseen by some 200 employees at several secret locations. But the reserve has never been properly replenished since the H1N1 pandemic, the swine flu of 2009.

On Feb. 5, Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar requested $4 billion from the White House to order supplies needed in the battle against the pandemic. But Azar didn’t get that money because Trump’s advisers still considered warnings about the virus to be exaggerated – and the president obviously feared that bad news would send stock prices plummeting. Trump also refused to make recommendations for dealing with the epidemic.

On Feb. 25, Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans reached their climax, with tens of thousands of drinking and partying merrymakers winding their way through the city’s streets. Much like the après-ski bars in the Austrian town of Ischgl, which was one of the main infection corridors that brought the disease to Germany and other Western European countries, the carnival celebration was the ideal breeding ground for the pathogen,.

“We didn’t even think of cancelling Mardi Gras,” says Cynthia Lee Sheng, the president of Jefferson Parish, the country that borders New Orleans. “We knew the virus existed in other parts of the world, but we thought it could be contained in the U.S.”

“It’s Like a Miracle – It Will Disappear”

It was a misunderstanding, and it was largely Trump’s fault. Within days of when the celebrating throngs were working their way through Bourbon Street, the president told people in Washington to think of it as being a bit like the flu. Two days later, the president uttered the ultimate expression of his negligence in handling the crisis. “It’s going to disappear. One day – it’s like a miracle – it will disappear.”

Today, Jefferson Parish County has more deaths per capita than New York City. And like almost everywhere else in the U.S., it is hitting people at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder hardest. Even before the pandemic, Americans living under the poverty line were five times at greater risk of disease than wealthy people.

In the U.S., health insurance is often obtained through a person’s employer, meaning their health-care protection is directly tied to their job. People working in low-wage sectors like wait staff, cashiers or parcel carriers are often forced to get their own insurance. But that insurance is often too expensive, especially considering that the current minimum wage in many U.S. states is $7.25 an hour.

It’s no wonder, then, that the pandemic is affecting a disproportionately high number of African Americans, who on average have incomes 25 percent lower than those of white Americans. African Americans are also more likely than average to be employed in jobs where working from home isn’t possible and the risk of infection is high. By the middle of the week, 177 people had died from the virus in Chicago; and more the 70 percent of those who perished were African Americans, despite the fact that they comprise only one-third of the city’s population. “We are all together in this crisis,” said Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot. “But we are not all experiencing this crisis in the same way.”

Many presidents rise to the occasion in their nation’s hour of need: John F. Kennedy led his country through the Cuban missile crisis, George W. Bush listened to the advice of experts during the financial crisis of 2008. But Trump doesn’t see the virus as way of overcoming partisan rancour. On the contrary: He appears to view the virus as some kind of personal insult.

One of the reasons the pandemic is hitting the country so hard is that no one appears to be able to hold the president back from his whims. He has systematically removed independent thinkers and experts from the White House and the government. In just three years, four national security advisers, three chiefs of staff and two secretaries of defense came and went. In the early years it was the job of Trump’s chief of staff to talk the president out of rash decisions. But for almost two weeks now, that position has been held by Mark Meadows, an excitable, ultra-conservative former Congressman from North Carolina who earned his job by praising the president on Fox News.

“Trump has systematically bled the government dry,” says Julianne Smith, who served as deputy national security adviser to Joe Biden when he was vice president. Trump has failed to fill many important positions in the government or he has dissolved them altogether. In one particularly disastrous move, he abolished the pandemic task force in the National Security Council that President Barack Obama set up after the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

Trump has undoubtedly adopted a showman’s approach to the crisis. Rarely has the president been as present as he has been in the past three weeks, during which he has conducted daily press conferences that can run as long as two hours. His strategy of maximum publicity also appears to be working: The president’s approval ratings have never been higher than at the beginning of the corona crisis. But will that approval endure?

“Jaw-Dropping” Unemployment

When the U.S. slid into the Great Depression in 1929, then-President Herbert Hoover tried to keep the nation happy with one-liners. He said the debate about the economic crisis was hysterical and added: “What the country needs right now is a good big laugh. If someone could get off a good joke every 10 days, I think our troubles would be over.”

But Americans soon lost interest in the president’s slogans and started looking at the hard economic facts. During the fall of 1932, the U.S. had an unemployment rate of almost 24 percent. Economic output fell that year by 12.9 percent. During the presidential election on Nov. 8, 1932, Democratic candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt won a crushing victory over Hoover, the Republican incumbent.

There is little to suggest at the moment that the American economy will recover quickly. The growing number of unemployed in America is often described in the U.S. media as”jaw-dropping.” In the past three weeks alone, more than 15 million Americans have applied for unemployment benefits. Goldman Sachs is expecting a 34 percent decline in gross domestic product during the second quarter of this year. The bank is forecasting a 6.2 percent decline of the economy for 2020 as a whole. “Never in American history has a president with such poor economic data been re-elected,” says Michael Green, a White House staffer under George W. Bush who now teaches at Georgetown University.

The virus has already ravaged every sector of the U.S. economy. First it hit bars, restaurants and movie theaters and people like Matthew Viragh, who runs two art-house cinemas in Brooklyn. The Nitehawk cinemas are known throughout the city. You can order food and wine during screenings, and its program is finely curated, showing independent and art-house fare, as well as “Nitehawk Naughties” midnight screenings, with series like the best of “Scandinavian Erotic Cinema from the Early 1970s.”

But that’s all over now. On March 13, Viragh had to lay off his 190 employees — his managers, program planners, cooks, bartenders and projectionists. Employees were allowed to take home the remaining food and the last bottles of alcohol. Viragh gave a very emotional farewell speech. “We wanted to hug, but were not allowed to,” Viragh recalls.

Cinemas are probably among the last establishments that will be reopened once the lockdowns are loosened. Viragh says movie theaters closed in mid-January in China, and so far none of them have reopened. Viragh’s biggest worry is that his customers will have gotten so used to streaming at home by then that they will choose to sit on the couch instead of going to the cinema. “Our complicated model won’t work unless we’re operating at a minimum of 50 percent of our capacity.”

It is already becoming clear now that the U.S. is far less well equipped for fighting the economic pandemic than other countries. “There has never been anything like this before,” says U.S. economist Justin Wolfers. “We’re in hibernation. And nobody knows when we will come out of it.”

Existential

Europe’s social welfare states are proving to be better prepared for keeping economies afloat in the shutdown, with measures like Germany’s short-time work furlough program and government-backed loans for companies. In the U.S., it remains unclear how the rescue funds from the government’s massive $2.3 trillion package are going to reach recipients. Meanwhile, many small- and medium-sized businesses are already in existential peril. Companies like Matthew Viragh’s art house cinema face a grim challenge. And so do people like Greg Turner and Lindsey Karlin.

Turner and his partner Karlin have now inched forward about the length of a baseball field in the line for the Food Bank in Alameda. Karlin, 42, lost her job as a cashier at a deli in nearby Oakland. Until three weeks ago, they were still earning around $6,000 a month between the two of them, which isn’t a lavish income in the expensive San Francisco Bay Area, but now Turner says they are making “exactly zero.” They have also lost their health insurance, which was linked to their employers.

Both have tried to sign up for the Cares unemployment program relaunched by Congress to help people make ends meet over the next few months, “but the website keeps crashing,” says Karlin, “everything is totally overloaded.” They’ve also been trying to get through on the telephone hotline, but they’ve had no luck there either. Hundreds of thousands of Americans are going through similar experiences right now. They’re sitting at home in front of their computers trying to figure out what to do with their lives now that they are unemployed.

For small and medium-sized companies, the stimulus package included an initial provision of $350 billion, which the government wants to quickly increase by another $250 billion due to the huge demand. U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin declared that the loans would be granted on a “first come, first serve” basis, which may have contributed to the fact that banks were totally inundated with inquiries at the beginning of April. “Many things are still going wrong because the system isn’t designed for this kind of state intervention,” says Wolfers.

“Total Devastation”

David Kong, CEO of the Best Western chain and one of the most powerful men in the American hotel industry, has laid off or suspended several thousand people in recent weeks. Not personally, of course. Hotel managers took care of that. Kong is working from home in Phoenix now, and the numbers currently landing on his desk are so dramatic that there is “nothing I can meaningfully compare it to,” as he puts it. “In the last economic crisis in 2009, we had a 16-percent drop. And at the time, we all thought that was massive.” Today business is down by 90 percent. Kong describes it as “total devastation.”

King attended a meeting President Trump scheduled with top hotel industry executives at the White House in March. Everyone was there – the CEOs of Hilton, Marriott, InterContinental and Hyatt. A transcript of the meeting reads almost as if it were a competition for who could come up with the worst news. Trump acknowledged each summary with a “thank you very much.” Trump is a hotel owner himself, he “understands the problem,” says Kong. “He really wants to help us.” But he says the aid package passed by Congress is too small. “It’s simply too little money, much less than we expected.”

For the U.S. economy, the corona crisis is a fall from a very high horse. Up until recently, the U.S. was considered the world’s unrivaled, leading economic power – with the most valuable companies, the biggest financial markets, the most important currency. By almost all comparative measures, the United States was leading during the past decade. Its economic growth figures were also usually greater than those of other developed countries, including in Europe.

This country, whose wealth was once dependent on oil imports from the Middle East, had also risen up as an energy exporter. And never before had a single national economy dominated the world’s future-oriented industries as much as the U.S. with its digital sector. Economic crises didn’t seem to affect the U.S., which quickly overcame the 2008 financial crash.

This makes it all the U.S.’s sudden, apparent vulnerability all the more surprising, a weakness spurred by Trump’s mismanagement, but also by the fundamental flaws in its health-care system. Overnight, the economic wellbeing of the country stopped being dependent on the adaptability of its companies and the financial power of its government, but rather on the number of intensive-care beds available.

The End of American Economic Dominance?

Some economic scientists expect the coronavirus recession to be deeper in the U.S. than in many other industrialized countries. Recent forecasts estimate that its economy will shrink between 4 and 7 percent when calculated over the entire year. A growing number of economists are also losing hope that the collapse will be followed by a swift recovery.

According to one analysis by Deutsche Bank, many companies and households will at first save money to pay off debts they have accumulated in the crisis. Analysts at the bank believe this would result in the economy taking not a V shape, but a U-shaped curve, meaning the collapse will be followed by a period of stagnation before growth starts again. New York University economics expert Nouriel Roubini believes even that is optimistic. He has recently begun speaking of an “I” scenario, a vertical, nearly uninterrupted decline in the economy, without any recovery in sight.

Some economists fear that the corona crisis could spell the end of American economic dominance. Harvard University’s Kenneth Rogoff argues that, even though we shouldn’t underestimate the U.S.’s ability to creatively overcome adversity, it is unclear if it will succeed this time. He says that the pandemic could “prove to be the greatest threat to U.S. leadership and primacy of the dollar since World War II.”

So will the virus put an end to the country’s superpower status? Doshi, the Washington political scientist, believes that if the U.S. proves itself incapable of leadership, global power relations could shift in favor of Beijing.

Predictions Are Premature

That said, the end of American dominance has often been predicted in the past. On Oct. 4, 1957, the Americans grew terrified when Moscow sent the first-ever satellite, Sputnik 1, into space. People saw it as a sign of the Soviets’ technological dominance over the U.S.

But then the nation once again stirred. The event led not only to the founding of NASA, the American space agency, but to the investment of billions of dollars by the federal government in the public school system, in an effort to interest young people in physics and mathematics. On July 21, 1969, Neil Armstrong of Wapakoneta, Ohio, became the first person to set foot on the moon.

There are now signs that the country is coming to its senses. Most Americans are, even without orders from the authorities, exercising social distancing from each other, thus ensuring that the virus spreads more slowly. A clear majority of Americans are now in favor of the U.S. government providing responsible health-care insurance for American citizens. On Wednesday, the Democrats finally agreed on a candidate for the presidential election, set to take place on Nov. 3, after socialist candidate Bernie Sanders withdrew his candidacy and promised to support former Vice President Joe Biden. The latter is now Trump’s opponent, although he faces a shortage of money and is struggling with the fact that nobody is currently showing interest in him.

In the U.S., every schoolchild learns the saying, “pull yourself up by your bootstraps.” To actually pull one’s bootstraps, it turns out, is physically impossible. But that’s precisely what makes it so appealing.

Trump’s Quotes on the Coronavirus:

Jan. 22

“We have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s going to be just fine.”

Feb. 19

“I think it’s going to work out fine. I think when we get into April and the warmer weather, that has a very negative effect on that.”

Feb. 26

“We only have 15 people, and they’re getting better and hopefully they’re all better soon.”

Feb. 28

“Now the Democrats are politicizing the coronavirus. And this is their new hoax.”

March 15

“It’s a very contagious virus. It’s incredible, but it’s something that we have tremendous control over.”

March 16

“I was talking about what we’re doing is under control, but I’m not talking about the virus.”

March 17

“I have a feeling that a lot of the numbers that are being said in some areas are just bigger than they are going to be.

March 24

“I would love to have it open by Easter. Wouldn’t it be great to have all the churches full?”

March 29

“If we can hold that down, as we’re saying, to 100,000 — it’s a horrible number — maybe even less. But to 100,000. We all together have done a very good job.”

Featured image: Illustration: Michael Meissner & Mona Eing / DER SPIEGEL

- orinocotribunehttps://orinocotribune.com/author/orinocotribune/

- orinocotribunehttps://orinocotribune.com/author/orinocotribune/April 24, 2024

- orinocotribunehttps://orinocotribune.com/author/orinocotribune/

- orinocotribunehttps://orinocotribune.com/author/orinocotribune/April 23, 2024

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)