US and OAS Lobby for Nicaraguan “Political Prisoners” who Butcher Their Pregnant Girlfriends

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

Ben Norton reports from Nicaragua, where the US embassy and OAS successfully lobbied for the release of violent criminals who led a coup attempt in 2018. Some of these so-called “political prisoners” have stabbed their pregnant girlfriends to death, raped, and murdered.

JINOTEPE, NICARAGUA – “It was wrong to let him out. Because maybe if he were locked up he wouldn’t have killed my niece,” Yadira Acevedo cried out, holding back tears.

“What we are asking for is justice,” she continued as she showed me photos of the young woman, Ruth Aburto, on her cracked phone.

On her niece’s killer, the message was simple: “He has to pay!”

Were it not for the efforts of Nicaragua’s political opposition, or for pressure from the US government, Aburto would be alive today.

Tragically, her boyfriend’s name appeared on a database of supposed “political prisoners” compiled by a top US government-backed opposition group. Many of these figures had been jailed for their participation in the violent 2018 attempt to overthrow Nicaragua’s democratically elected government — a failed putsch that relied on heavy participation from career criminals to maintain economically punishing roadblocks around the country.

Aburto’s would-be killer was freed in a 2019 amnesty process demanded by Washington and the Organization of American States. He went on to stab his pregnant 22-year-old girlfriend in the back of the head three times, leaving her to die in a puddle of her own blood.

Other supposed political prisoners the Nicaraguan opposition advocated for had been convicted not of political violence, but rather of crimes like murder, rape, and drug trafficking.

The sweeping pardons of these prisoners were controversial among the leftist base of Nicaragua’s ruling Sandinista government. Many activists had seen their friends and loved ones tortured and even brutally murdered by the prisoners during the coup attempt, and wanted them to serve their time.

But the pressure on the Nicaraguan government to release the imprisoned insurgents was intense and multifaceted; it came not only from inside the country, but also from powerful forces abroad, including the United States, the Organization of American States (OAS), and well-funded international human rights NGOs.

The release of these prisoners in the amnesty process has resulted in a new series of crimes that have shaken Nicaraguan society, raising questions about the true agenda of the country’s political opposition and its relationship to violent criminal networks.

I traveled to Nicaragua to speak with family members of the victims and chronicle the shocking story of how the right-wing political opposition, business elites, the US government, and the OAS joined forces to free a collection of murderers, rapists, and drug dealers they had branded as courageous dissidents.

Throughout my reporting, I met with bereaved family members who told me through tears that the released criminals were “psychopaths” who should have stayed behind bars. They implored the international media to draw attention to their plight — but so far, the English-language press has ignored the scandal.

“I think that if the [opposition umbrella group] Civic Alliance claims he is a ‘political prisoner,’ they are going to let him out again, and I think that is not right,” Ruth’s cousin Rosa Acevedo remarked to me. “He is a killer.”

“This kind of person,” she continued, her voice filled with contempt, “they are society’s parasites, scum!”

Pardoned ‘political prisoner’ stabs his pregnant girlfriend to death

Throughout the 2018 coup attempt, and in the aftermath, Nicaragua’s US-backed opposition incessantly demanded the release of all supposed political prisoners, immediately, without condition.

What exactly made someone a political prisoner was difficult to define. Major opposition groups threw around the term liberally, essentially to refer to all those detained in the coup attempt. Hundreds of insurgents were locked up for crimes committed in the “tranques,” or barricades the putschists had erected in an attempt to paralyze the country and wrest territory away from the Sandinista government.

By July 19, 2018, the US-backed coup efforts that had been launched in April had fizzled out. This date marked the annual celebration of the 1979 Sandinista Revolution, in which revolutionaries ousted a right-wing military dictatorship that had for decades been propped up by Washington, and hundreds of thousands of Nicaraguans gathered in the capital Managua to commemorate the uprising — and demand peace.

But the failure of the three-month putsch did not ensure the kind of stability the country had enjoyed for so many years following its civil war in the 1980s. So President Daniel Ortega launched a Commission of Truth, Justice, and Peace to oversee the creation of 10,000 local-level reconciliation committees that could bring the country back together.

Under heavy pressure from the US government, OAS, and international media, the Sandinista government agreed in February 2019 to negotiate with the opposition for a general amnesty for prisoners.

The group of “political prisoners” that ended up being advocated for in these negotiations was ultimately chosen by the Alianza Cívica por la Justicia y la Democracia, or Civic Alliance for Justice and Democracy (ACJD), a coalition of right-wing opposition groups and business elites that had been formed during the 2018 coup attempt, with the backing of the US government.

The Civic Alliance, which is led by wealthy families who ruled Nicaragua before the Sandinistas took power and which coordinates closely with Washington and the OAS, sat across the table from the government in the amnesty talks, serving as the official voice of the opposition.

The Civic Alliance selected the group of “political prisoners” to be freed using the research of closely allied opposition groups: the Comité Pro Liberación de Presos Políticos (Committee Pro-Liberation of Political Prisoners) and the Centro Nicaragüense de Derechos Humanos, or Nicaraguan Center for Human Rights (CENIDH). The latter organization has been heavily criticized for publishing dubious, compromised data on the death toll during the 2018 coup attempt.

This case was no exception to the troubling trend. The committee and CENIDH used data sets that were almost identical, and which included numerous murderers and rapists, some of whom were arrested well before the coup attempt had even started.

On the first day of these amnesty negotiations, February 27, President Ortega approved a major concession: the release of 100 prisoners who were included in the opposition’s database. This diplomatic gesture was followed by a series of pardons of hundreds more “political prisoners” in the months that came after.

Ortega’s compromise was celebrated by the press, which blindly echoed the opposition’s perspective. Spain’s top newspaper El País uncritically referred to the pardoned criminals as “political prisoners.” The corporate transnational giant Univision adopted the same language, as did the US government’s Voice of America.

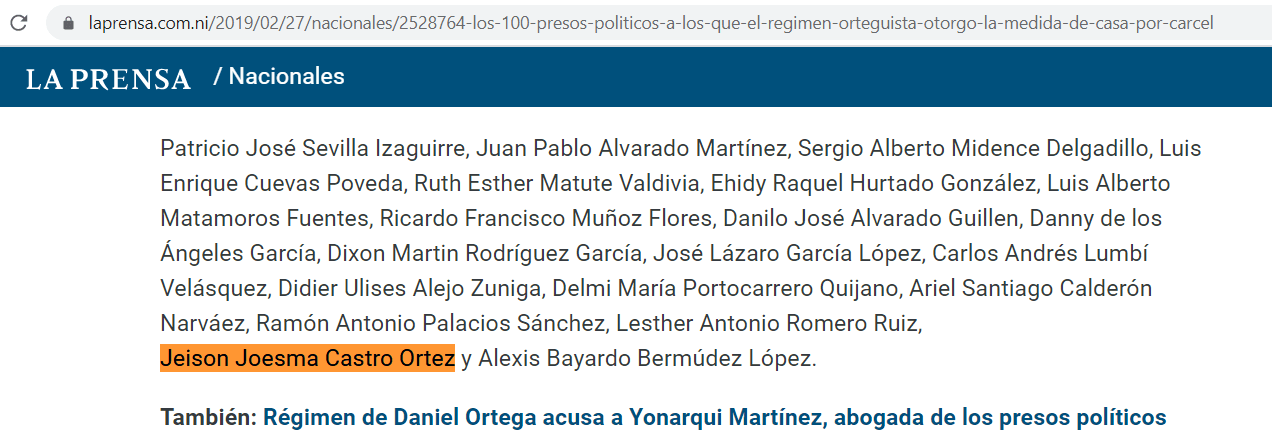

Nicaragua’s La Prensa, a right-wing voice of the opposition that has historically been heavily funded by the US government to push anti-Sandinista propaganda, published a report that same day listing the 100 “political prisoners” who were freed by the “Ortega regime.”

One of the men included on La Prensa’s list was Jeison Joesma Castro Ortez. He had originally been arrested in July 2018, in the middle of the coup attempt, and was sentenced to 13 years in prison on charges of terrorism, armed robbery, and organized crime.

Nicaraguan police officials said he had tried to set off a makeshift bomb near a police barracks in the city of Jinotepe. Castro Ortez was sentenced with attempting to kill and rob people as they passed through the roadblock he manned.

Castro Ortez similarly appeared in the database of “political prisoners” compiled by the Civic Alliance-aligned opposition groups CENIDH and the Committee Pro-Liberation of Political Prisoners, which they published at the website NicasPresosPoliticos.org and subsequently used in the amnesty talks.

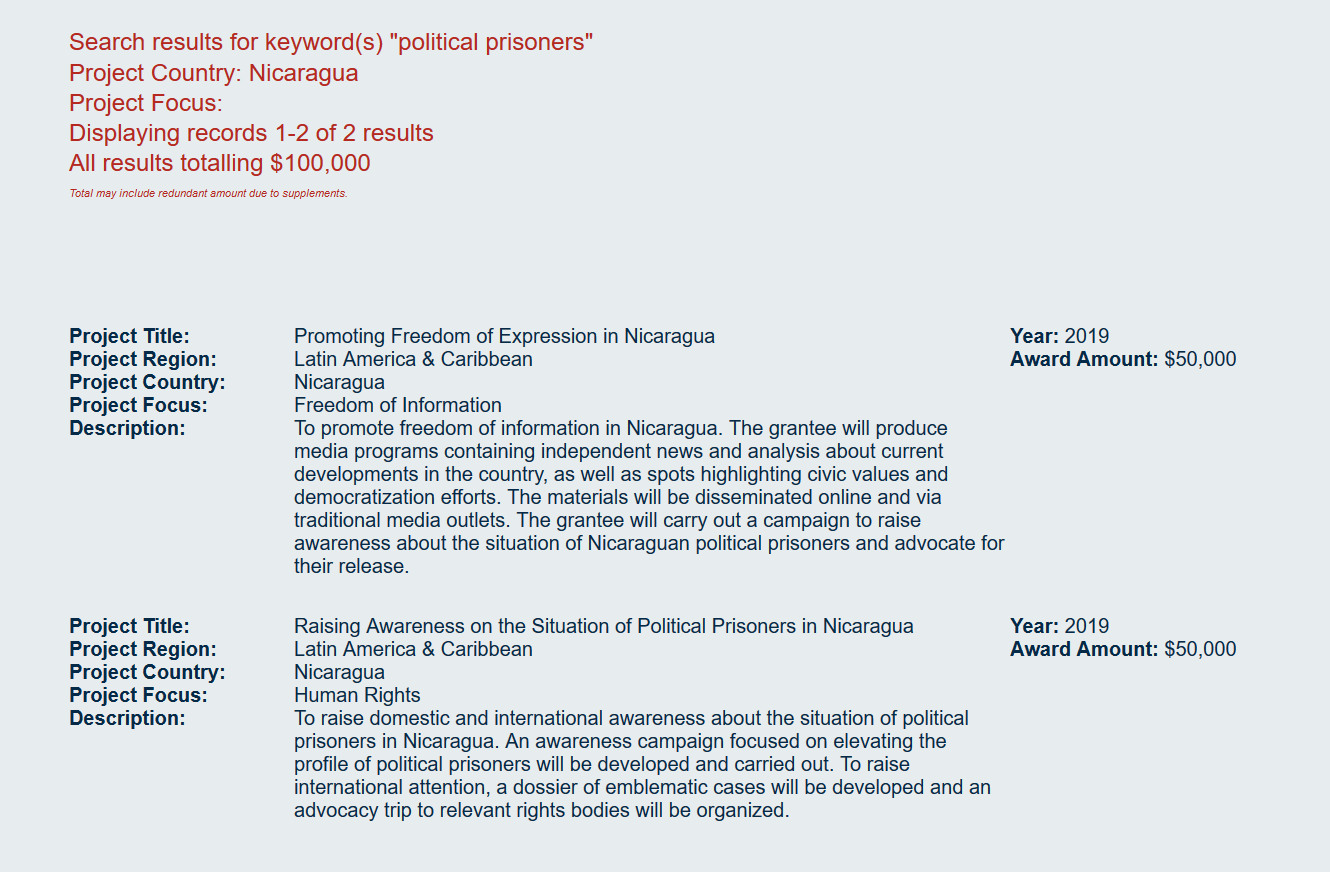

This “political prisoners” advocacy group also appears to be funded by the US government’s regime-change arm, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), a major source of financing for Nicaragua’s opposition.

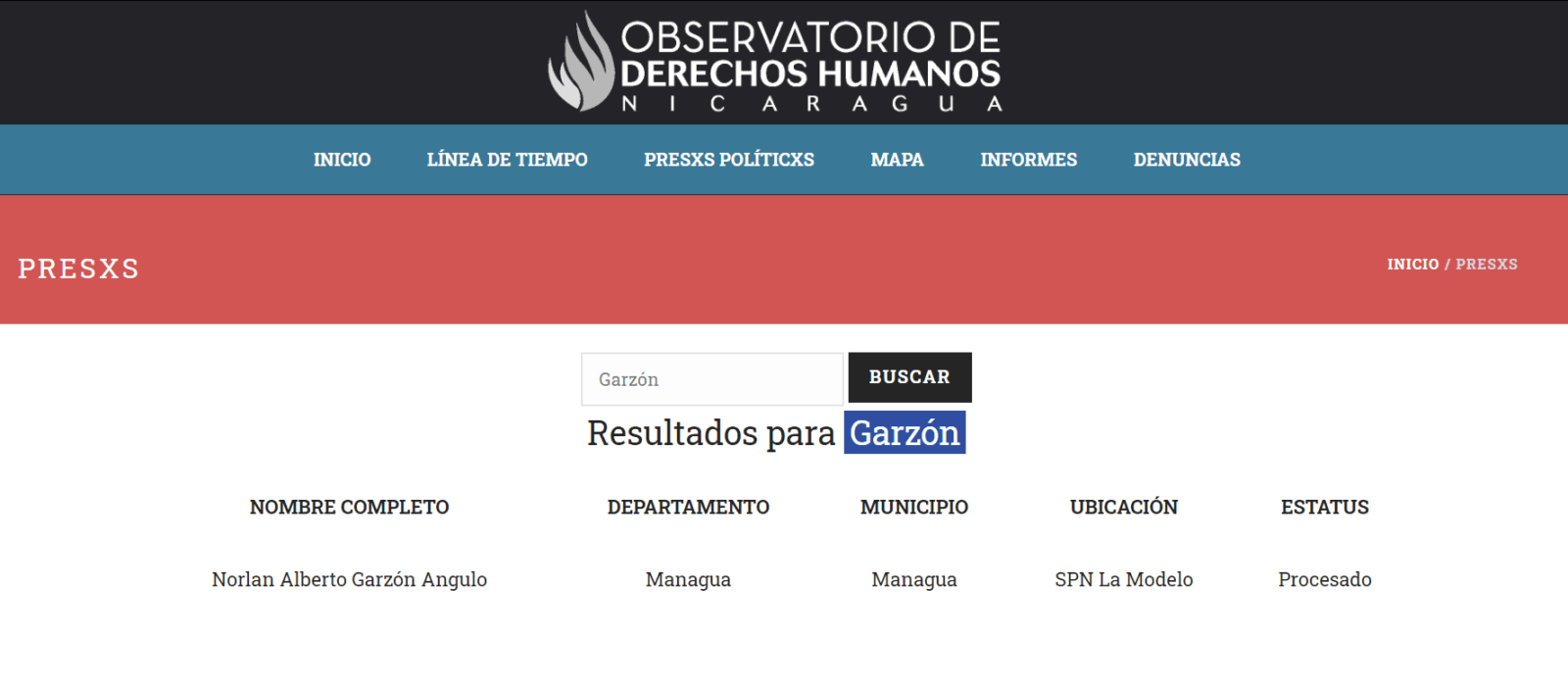

And once again, Castro Ortez was likewise included in the list of “political prisoners” compiled by the Observatorio de Derechos Humanos Nicaragua, or Nicaragua Observatory of Human Rights. On its website, this opposition group attributes its findings to CENIDH, the Committee for Liberation of Political Prisoners, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and the United Nations.

While foreign-backed ostensible “human rights” organizations vigorously lobbied for the release of prisoners like Castro Ortez, their advocacy has ultimately led to more senseless violence across Nicaragua.

Indeed, after being released in February 2019, this supposed “political prisoner” returned to his violent ways.

The lonesome death of Ruth Aburto

In January 2020, a young woman named Ruth Elizabeth Aburto Acevedo was brutally murdered in her home in the city of Jinotepe. Her boyfriend had killed her, first puncturing her hand and then stabbing her three times in the back of the head. He subsequently fled the scene, leaving her to die in her own blood, before he was eventually apprehended by the police.

Aburto was just 22 years old at the time. And she had been pregnant. Her boyfriend also killed their unborn child.

The man who murdered her in such a monstrous fashion was named Jeison Castro Ortez — the same so-called “political prisoner” whose release the opposition had successfully secured less than 11 months before.

Nicaraguan outlets like La Prensa and 100% Noticias have published a stream of reports on the notorious femicide. But the coverage in these right-wing mouthpieces has conveniently failed to mention that the killer’s freedom – and his girlfriend’s heinous death – were the byproducts of opposition lobbying.

Family members of victim denounce release of ‘psychopath’ killer

I traveled to a small village on the outskirts of Jinotepe, Nicaragua, roughly an hour and a half drive outside the capital, to speak with members of Ruth Aburto Acevedo’s family.

Inside the home where Ruth was raised, a modest structure with a new coat of bright yellow paint outside and a breezy interior, I met Ruth’s aunt and two of her cousins.

The sense of grief was immediately palpable. Ruth’s mother had died roughly a year before she was killed. Worried that the victim’s grandmother, who is in poor health and has been bed-ridden since the news broke, could not bear to know the real story, the family told her instead that Ruth passed away in an accident.

I spoke first with Ruth’s aunt, Yadira Araceli Acevedo Vado. Through tears, Yadira described Ruth as a hard-working nurse who loved her job and was passionate about helping people.

Yadira also repeatedly described her late niece’s boyfriend as “a killer and a psychopath,” a criminal who frightened her in the few encounters they had.

She lamented that he was released from prison, insisting, “It was wrong to let him out. Because maybe if he were locked up he wouldn’t have killed my niece.”

“What we are asking for is justice,” she stressed. “He has to pay.”

Her description of Jeison Castro Ortez fit that of the archetypal “vandálico,” a term Nicaraguans use to refer to the violent criminals who participated in the coup attempt.

In popular discourse, pro-government Nicaraguans (who make up roughly two-thirds of the population) refer to those who participated in the tranques as “criminales” and “delincuentes,” criminals and delinquents.

Some of the coup’s participants have admitted that they were paid for their activities — and not just with cash, but with drugs. In our interview, Yadira’s characterization of Castro Ortez reflected this image.

“She was going out with this man for four months,” Yadira explained. “We always saw him as strange. He would always bring her, and then he would leave. They came together, and he would always leave her. But we never thought it would come to this.”

“And sometimes I told her, because one day she showed up with a black eye, and I asked her, ‘Ruth, what happened to you?’ I hugged her, and I gave her a kiss. She lifted her head and told me, ‘Auntie, nothing. Nothing is going on with me.’ So I told her, ‘Look, tell us if this man did something to you.’ She dropped her head and didn’t say anything,” her aunt recalled.

Yadira described Ruth as a kind young woman with a loving heart, who ultimately found herself stuck in a tragic situation she could not extricate herself from.

“Unfortunately she met this man, this animal, on her path,” the aunt reflected. “And now what we want is justice, so there is not impunity, so that he pays for what he did. “And her siblings, all of us are destroyed. And my mother is there in bed, shattered.”

Yadira repeatedly referred to Castro Ortez as a “psychopath” and an “animal.” She said he made violent comments when they first met.

“One day he was like interrogating her,” she recalled. “So I said to him, ‘Are you jealous?’ [And he responded] ‘Yes! I’m jealous. So much I could even kill my own mother out of jealousy.’ That’s how he answered me.”

Yadira noticed that Ruth began to transform during her short four-month relationship with Castro Ortez. He took her phone and deleted apps like Whatsapp and Facebook, cutting her off from friends and family. He even forced her to dress differently.

“It was domestic violence, what he did. Simply because he is a psychopath and a killer,” Yadira said, adding that he had a child with another former girlfriend whom he had threatened with violence.

She recalled how Castro Ortez participated in the violent opposition barricades in Jinotepe, one of the key sites of indiscriminate violence against members of the Sandinista front.

“In Jinotepe, yes, he was there. But we didn’t realize until now that he did what he did. He was quiet about it,” Yadira said. “He even killed people. That’s what people say. He killed people there.”

She added, “If he was capable of doing that to my niece as he did, in cold blood, imagine how he killed her and all that, he tortured her and all that, you can imagine he was capable of doing other things.”

Ruth’s aunt said she had never heard Castro Ortez talk about politics. She assumed he was paid to participate in the tranques.

He had a shady past before the coup attempt, Yadira noted: “I know that he said he was in Colombia for a long time, and that after he was in Panama.” What he was doing in Colombia and Panama was not clear.

When I told Yadira that Castro Ortez had been included on the opposition’s list of political prisoners, she reacted with bewilderment.

“It was wrong to let him out. Because maybe if he were locked up he wouldn’t have killed my niece. Because what he did really hurts,” she said.

“We want him to pay for what he did. We don’t want him to come out. We want them to give him the maximum punishment. He is a person who does not deserve any forgiveness, none at all. He cannot leave from there,” Yadira stressed.

She added, “And we are asking for help from the media and everything, that they help us with that.”

‘What he did is femicide’

Rosa Idalia Acevedo Acevedo, one of Ruth’s cousins, was visibly angry at the February 2018 release of so-called “political prisoners” like Jeison Castro Ortez.

“People like this should not exist, in my opinion. Because in four months, he had four months to get to know her, and to commit this barbarism against her as he did,” she said. “Not just that he killed her, but also that before killing her, he chased her around the room, and first he tortured her.”

Rosa added, “People like that, I don’t think they should exist or be alive, because he didn’t stop after the first stabbing. He stabbed her again and again, until the third time, until he killed her.”

The cousin noted that Ruth’s mother had died roughly a year before she herself was killed. This left Ruth to take care of her two siblings.

Roughly 15 days before she was killed, Ruth had also visited them at the house where we spoke and told them she had plans to keep studying, and that she had just enrolled in a university. She had been planning for the future, before her life was cut short.

“What we are asking for is that the government creates justice. For the people who kill, and rape, they should not be let out of prison. They need to stay there. Because if they get out, they get out with even more force. And more of a desire to kill and rape,” she said.

Rosa also independently confirmed that Castro Ortez had been in the violent barricades in Jinotepe during the coup attempt.

“He was participating in the tranques. But we didn’t realize it at first,” she said. “We didn’t know if he did anything to anybody else. Until now.”

The cousin suspected that he had killed other people. She noted that he traveled a lot, and that there was another murder of a young woman in the Cazaro department where they live.

“On Facebook, people sent lots of things, and that sent me something saying she was not the first [murder victim],” Rosa recalled.

She was even more forceful in her condemnation of the people who lobbied for the release of Castro Ortez.

“I think that if the Civic Alliance claims he is a ‘political prisoner,’ they are going to let him out again, and I think that is not right. He is a killer,” Rosa said.

She called on the opposition to do better research. “They have to investigate people well.”

“What we want is justice. She was pregnant. So it is a double homicide. And this has to be looked at very closely. Because I don’t think they’re going to give just 20 years or 10 years to someone who killed a person and a baby.”

Rosa added, “This kind of person, they are society’s parasites, scum.”

Another cousin of Ruth, Maykeling Acevedo, stressed in comments to me that Castro Ortez never should have been let out of prison, and that those who lobbied for his release have blood on their hands.

“What he did is femicide. He was not a political prisoner,” Maykeling said. “This is ridiculous, what the Civic Alliance said, he is a woman killer.”

Maykeling, who like Ruth works in Nicaragua’s health sector, told me, “We want him to be thrown in prison. We want justice.”

Man accused of murdering elderly woman in 2016 on the list of ‘political prisoners’

Jeison Castro Ortez was not the only violent criminal who was included on the Nicaraguan opposition’s list of supposed “political prisoners.”

Another man included in the database, Norlan Alberto Garzón Angulo, was arrested back in 2016 — well before the coup attempt began in 2018 — and accused along with another man of raping and murdering an 82-year-old woman.

In March 2017, his co-defendant was sentenced to 35 years for rape and murder, charges he accepted. But Garzón Angulo continued denying involvement in the crimes. He had reportedly been trying to use claims of insanity to get the case dropped.

This alleged case of rape and murder of an elderly woman did not stop Nicaragua’s right-wing opposition and its coterie of so-called “human rights” organizations from listing Garzón Angulo as a political prisoner.

There are similar reports of other supposed “political prisoners” who were released in the US government- and OAS-backed amnesty process who were accused of murder or rape. But thus far, this scandal has received no English-language media attention.

US embassy lobbies for release of violent ‘political prisoners’

The pressure that foreign powers put on Nicaragua to release these so-called “political prisoners” was tremendous. And that pressure continues to this day, even after the Sandinista government has made numerous major concessions and passed a landmark amnesty law.

The US government and Organization of American States were deeply involved in the amnesty process and the campaign to release “political prisoners.” Both institutions worked closely with the right-wing opposition and lobbied for the release of killers like Jeison Castro Ortez.

Throughout the 2018 coup attempt, the US embassy in Nicaragua constantly demanded “the unconditional release of all political prisoners,” in statement after statement. When President Ortega initiated talks to pardon and release the incarcerated insurgents, the US ambassador to Nicaragua, Kevin K. Sullivan, tweeted approval: “The commitment to free all the political prisoners is a positive step. They should be freed as soon as possible.”

In these efforts, Washington relied heavily on the opposition Civic Alliance and its list of supposed “political prisoners,” repeatedly emphasizing in official government press releases, “The United States continues to support the Civic Alliance of Nicaragua in its efforts to represent the interests of Nicaraguans advocating for freedom, justice, democracy, and change.”

The Civic Alliance has acted as a cat’s paw of the US government, coordinating closely with the Trump administration to ratchet up the pressure against the elected Sandinista government.

Hoy me reuní con la Nicaragua Freedom Coalition en #WashingtonDC. Su importante trabajo en la diáspora nicaragüense une esfuerzos de los que promueven la democracia en #Nicaragua con @AlianzaCivicaNi y @UnidadNic #UnidadNacional pic.twitter.com/9xHlmwN3Jf

— Chargé d'Affaires Kevin O'Reilly (@USAmbNicaragua) June 3, 2019

When the process of dialogue with President Ortega began in February 2019, the Civic Alliance acted as the official voice of the opposition — and the US government served as its political big brother and international sponsor. The partnership was so obvious that the Sandinista government initially proposed to release those on the group’s “political prisoners” list only if the Civic Alliance agreed to ask its backers in Washington to lift US sanctions, which have undermined Nicaragua’s economy and increased hardships for the country’s working-class.

The US government has also bankrolled the “political prisoner” network that pushed for the amnesty. The National Endowment of Democracy (NED), a CIA cutout that advances US soft-power interests by funding opposition forces in foreign countries targeted for regime change, gave at least $50,000 in 2019 to a group dedicated to “raising awareness on the situation of political prisoners in Nicaragua,” according to a search of the NED grants database.

The specific organization is not named, but it clearly refers to opposition groups that work under the umbrella of the Civic Alliance. ($50,000 may not be much in the US, but in Nicaragua, the second-poorest country in the Western hemisphere, where the minimum wage is around $200 to $300 per month, it is a substantial sum of money.)

The Grayzone sent a detailed request for comment to the US embassy in Nicaragua, describing the contents of this report and the scandal involving Jeison Castor Ortez. A representative from the US embassy replied several days later with two generic sentences: “The State Department has released a number of statements regarding US policy toward Nicaragua. We don’t have anything further to add but appreciate your giving us the opportunity.”

‘Human rights’ groups join the campaign, and lobby for sanctions

Joining the US government in the massive pressure campaign against Nicaragua were major international “human rights” organizations like Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Amnesty International. Both of these groups have long been criticized for functioning as arms of the US government and upholding blatant double standards toward Western allies.

During the 2018 coup attempt in Nicaragua, HRW and Amnesty International placed the blame squarely on the government for the violence, scarcely ever mentioning the extreme violence of the opposition criminals who set people on fire, murdered Sandinista activists, shot police with mortar cannons, and burned down houses of leftists.

Amnesty International lobbied for the UN Human Rights Council to take punitive action against Nicaragua while echoing the highly questionable claims of the Civic Alliance and Committee Pro-Liberation of Political Prisoners without an ounce of skepticism, simply identifying them as “local groups,” as if they were politically neutral.

HRW deployed these alleged “political prisoners” as justification for its call for sanctions on the Nicaraguan government. The group wrote, “Governments in the Americas and Europe should impose targeted sanctions against top Nicaraguan authorities.”

HRW Americas director José Miguel Vivanco went on to lobby the US, Canada, and right-wing countries in Latin America to “double-down on sanctions” against Nicaragua as punishment for holding the prisoners.

OAS works with right-wing Nicaraguan opposition to push for release of ‘political prisoners’

The Sandinista government also faced significant pressure from the Organization of American States (OAS). While posing as an unbiased arbiter of affairs across the Western hemisphere, this organization receives most of its funding from the US government. In fact, the 2018 Congressional Budget Justification stated very clearly that the OAS “promotes U.S. political and economic interests in the Western Hemisphere by countering the influence of anti-U.S. countries such as Venezuela.”

RELATED CONTENT: It is Not Just Venezuela. Nicaragua is Also an Objective of Imperialism

Under the leadership of its fanatically pro-US secretary-general, Luis Almagro, the OAS has become a full-bore weapon of regime change targeting independent leftist governments in Latin America. The OAS played a crucial role spreading lies to drive the military coup in Bolivia, violated its own charter in its strong backing of the Trump administration’s coup attempts in Venezuela, and has set its sights on Nicaragua as well.

Throughout the 2018 coup attempt in Nicaragua, the OAS joined Washington in blaming the Sandinista Front for the violence, endlessly demonizing the democratically elected government with such a degree of vehemence that Almagro frequently calls it the “Ortega-Murillo regime,” a reference to Vice President Rosario Murillo.

And like the US government, the OAS acted as an international sponsor of the right-wing Civic Alliance in the amnesty talks. Almagro coordinates closely with the Nicaraguan opposition, regularly meeting with coup leaders and lobbying extensively on their behalf.

Me reuní con representantes de la Alianza Cívica por la Justicia y Democracia (ACJD) de #Nicaragua José Pallais, José Aguerri, Alvaro Vargas y Michael Healy. Es imprescindible la liberación completa de todos los presos políticos y la recuperación de las libertades en el país pic.twitter.com/eG0j9rKKlz

— Luis Almagro (@Almagro_OEA2015) May 30, 2019

The Grayzone contacted the OAS with a detailed request for comment. It did not reply.

Almagro has aggressively lobbied for Nicaragua to release its so-called “political prisoners.” In fact, a search of his more than 8,000 tweets shows the OAS chief has only ever mentioned the phrase “presos políticos” (political prisoners) in reference to Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba — the few socialist governments remaining in the region, dubbed by Washington the “troika of tyranny.”

Under Almagro’s leadership, the OAS does a weekly certification of the dubious list of supposed “political prisoners” in Venezuela, compiled by Foro Penal, a right-wing opposition group that is funded by and closely coordinates with the US government.

And while Almagro has incessantly called for Nicaragua (and Venezuela and Cuba) to release its supposed political prisoners, he acts as though no other countries in North or South America lock people up for political reasons — especially not the right-wing governments that Almagro supports so fervently.

Well over 100 activists were disappeared during the 2019 protests against the neoliberal policies of Chile’s billionaire President Sebastián Piñera. While obsessing over Nicaragua, Almagro has made no mention of them, and has remained noticeably reticent on rampant human rights violations in Colombia, another nation run by a right-wing US-friendly government.

When Nicaraguan President Ortega called for a peace process and dialogue with the opposition, Almagro took a maximalist position, demanding that the government release 770 so-called political prisoners as a condition for OAS participation.

Where did Almagro get the 770 figure from? His source, as usual, was the Civic Alliance and CENIDH, whose extremely dubious research the Civic Alliance relied on as well – and whose database of “political prisoners” includes numerous murderers and rapists.

While CENIDH purports to be a supposed human rights organization, it acts as a highly partisan voice for the opposition. John Perry reported for The Grayzone that CENIDH was founded by an opposition politician with European funding; that it uses openly biased language in its reports, referring to the elected government as a “dictatorial regime”; and inflates death tolls while blaming violence exclusively on the FSLN.

While reporting in Nicaragua, Grayzone editor Max Blumenthal documented the direct role CENIDH leadership played in the coup attempt against the Sandinista government. Independent Nicaraguan researcher Enrique Hendrix revealed how CENIDH, along with other opposition-allied “human rights” groups in Nicaragua, padded death counts by including “victims of traffic accidents, altercations between gangs, murders by robbery, those killed by accidental firing of a firearm and even more absurdly, a suicide.”

In response to the organization’s major role in the putsch attempt, Nicaragua’s National Assembly voted in December 2018 to revoke the legal status of CENIDH.

This has not deterred the so-called human rights arm of the OAS, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), from relying extensively on CENIDH and its highly questionable data. IACHR has endorsed CENIDH’s hyper-partisan figures without any skepticism, and even collaborated with the opposition group. IACHR has also lobbied on behalf of CENIDH, calling for the OAS’ legal arm the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to take action to protect it.

Facing this enormous, international pressure campaign, President Ortega agreed to release the supposed “political prisoners” in early 2019. The Nicaraguan government issued a series of pardons over several months: 100 freed in February, 50 more released in March, another 50 let out in April.

But the opposition was not content. It turned to international media outlets that acted as a megaphone for the Civic Alliance, amplifying its demands that all “political prisoners” be released.

This eventually culminated in June 2019, when the Sandinista-majority National Assembly passed a historic amnesty law, officially pardoning prisoners who were arrested after the coup attempt that began on April 18, 2018.

The OAS immediately praised the Sandinista government’s concession. In a statement, the organization said it “Welcomes the release of political prisoners and the fact that the agreements have allowed these people to rejoin their families.” Almagro likewise tweeted, “We welcome the freeing of the 56 political prisoners in Nicaragua according to the [Civic] Alliance-government agreement.”

But as soon as the amnesty law passed, the right-wing opposition and its international sponsors made it clear that this was not enough. The OAS’ Inter-American Commission on Human Rights criticized the law for not going far enough, just one day after the organization had welcomed it. The Catholic Church in Nicaragua – a major player in advancing the coup in 2018 – also complained that the concession was insufficient.

Just a few months later, Secretary-General Almagro clamored again for the Nicaraguan government to release more “political prisoners,” directly citing the dubious, highly partisan claims of the Civic Alliance.

The opposition-controlled corporate media in Nicaragua chimed in, rattling off one article after another claiming there were hundreds more “political prisoners.” Right-wing students from private universities like the University of Central America joined in as well, organizing protests demanding that they be freed.

Exigimos la liberación de los presos políticos que hay en #Nicaragua, según denuncia la Alianza Cívica por la Justicia y la Democracia @AlianzaCivicaNi #OEAconNicaragua https://t.co/11uZhvZMVO

— Luis Almagro (@Almagro_OEA2015) September 26, 2019

It was as if the government had not just spent months engaged in arduous negotiations that ended in an agreement for the release of hundreds of prisoners.

This relentless pressure campaign made it clear that the right-wing opposition in Nicaragua and its powerful backers abroad would not be truly content until it fulfilled its real goal: the full removal of the leftist Sandinista movement from power and its purging from public life.

Nicaraguan government says amnesty law was move for peace

As the right-wing opposition demands new rounds of concessions seemingly every week, some of the criminals they advocated for have been wreaking havoc across Nicaraguan society.

In Managua, I spoke to Edwin Castro Rivera, the leader of the Sandinista Front party, to better understand the logic behind the amnesty process. He was part of the committee that negotiated with the opposition, and co-authored the amnesty law.

Castro Rivera stressed the government’s demand for peace and stability. The violent US-backed Contra war that savaged Nicaragua in the 1980s had left the country divided, and most Nicaraguans feared a return to the neighbor-against-neighbor violence that tore the country apart.

“One of the things that the coup attempt affected the most, which we had earned in Nicaragua through much effort, is the effort to reunify Nicaraguan families,” he explained.

After winning the presidential election in 2006, Daniel Ortega declared the creation of a “Government of Reconciliation and National Unity.” This is still the name of Nicaragua’s government today.

“That unity we have earned through much effort, with the Government of Reconciliation and National Unity, that is why we call it that: Reconciliation and National Unity, because our objective was to reunify the families,” Castro Rivera said.

“And the coup attempt broke this unity once again. Since then, our main task, after restoring the calm in Nicaragua, was to go back to progressing and rebuilding the familial unity,” he added.

The 2018 putsch plunged Nicaragua into an epidemic of violence it had not seen in decades.

“They burnt people alive, and danced around them,” Castro Rivera said of the violent insurgents. “They tortured people who they stripped naked, and painted their bodies. We had never seen this.”

“You only see this in the narco activity in Mexico and in Colombia,” he added. “Because of this, we concluded that there was participation of Mexican and Colombian drug-trafficking groups. And criminals who were paid to do all this.”

I mentioned that Jeison Castro Ortez, the pardoned criminal who killed his pregnant girlfriend, had told her family members that he had spent time in Colombia, although he had not revealed what he was doing there. Castro Rivera was not surprised, and said other incarcerated people on the “political prisoner” list had also spent time in Colombia before the coup.

The Sandinista chief stressed that fears of this kind of violence returning is what led the Nicaraguan government to create the Commissions of Reconciliation and Peace, which have worked in small towns all across the country to try to unify the population.

Castro Rivera said the government felt it had no choice but to agree to an amnesty process with the opposition, to try to foster this unity.

“For us, it was a difficult problem, because how are we going to explain to our people, that the criminals who killed your son or your father in cold blood, we’re going to give them amnesty,” he explained.

“It was very bitter for us. But it had to be done if we wanted to reclaim the route of reconciliation, the reunification of families. And that was the essential motive of this amnesty.”

While the FSLN leader stressed that the government’s main goal behind the amnesty process was to try to bring the country together, he also conceded that there was a lot of foreign pressure on Nicaragua.

“We had pressure from the OAS,” Castro Rivera said. And that was compounded by the OAS’ “human rights” arm the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. He called the CIDH “totally biased.”

When the Sandinista government sat down at the dialogue table with the Civic Alliance in 2019, Castro Rivera said one of its main demands was the release of prisoners.

“In the first list of ‘political prisoners’ that they gave us, before the amnesty law, there was a man who murdered his grandmother,” he recalled. “To rob her. He was on drugs.”

This convict had also been arrested back in 2017, months before the coup attempt. Other violent criminals like him were included on the opposition’s list. Castro Rivera said the case of Jeison Castro Ortez is just one example of a much larger trend.

Because of the plethora of career criminals on the opposition’s amnesty list, the government insisted on a stipulation that those granted amnesty also pledge not to repeat the crimes that were pardoned for. This clause, Castro Rivera noted, was based on the Belfast Guidelines on Amnesty and Accountability, a United Nations-backed initiative led by experts in international law.

“And now they have another list of ‘political prisoners’ that are nothing more than criminals,” Castro Rivera said of the opposition’s latest calls for another amnesty process, just half a year later.

The Sandinista negotiation chief offered a few theories on the real goals behind the opposition’s incessant pressure campaign.

“We are a small country, with some economic difficulties, in addition to those that they created in the coup attempt,” Castro Rivera explained. “Our principal wealth is precisely the security and tranquility that is here in Nicaragua. And this is what they want to attack, these very small groups.”

“It is a small political group, with economic power, that is convinced that they will never come to power with votes, with the work that Daniel Ortega is doing,” he said. “Daniel’s sin is doing things for the people, and having the support that he has.”

In June 2017, the mainstream polling firm M&R Consultores found 78.3 percent of Nicaraguans approved of the management of the Nicaraguan government.

“So this group returns to the tradition” that plagued Nicaragua for decades, Castro Rivera stated: “changing the government with weapons, through a coup d’etat.”

Like the other Nicaraguans I spoke to, the FSLN leader lamented the lack of international media coverage of the scandals shaking his country, or of the government’s sacrifices for peace.

“In my experience, the peace processes normally are not in the news. Not only in the English-language media, all over the world,” he said.

“If there is conflict, automatically it is all over the media. But when the process of peace, tranquility, and normality begins — which you can see here in Nicaragua, in the street, people doing normal activities, economic activities, we return to being the safest country in Central America.”

More opposition violence threatens Nicaragua’s rare stability

While Nicaragua’s right-wing opposition boasts powerful sponsors in Washington, it has little influence at home. The polling firm M&R found in January 2020 that 63.5 percent of Nicaraguans plan to vote for the Sandinista Front in the 2021 election, whereas only around 11.5 percent of the population actively support the opposition.

Popular enthusiasm for the Sandinistas is made clear with heavily attended, festive marches held in Managua each Saturday. Meanwhile, the opposition spends much of its time in closed-door meetings with business people and representatives of foreign governments and organizations.

The source of popular support for the Sandinista Front is also apparent: The government has drastically reduced inequality; created systems of free, universal healthcare and education; empowered women, attaining the world’s fifth-highest level of gender equality; and managed to bring Nicaragua the peace and stability that has been elusive in Central America’s violence-ridden Northern Triangle.

But the sweeping prisoner amnesty the government granted under massive pressure by the opposition and the US has thrown the country’s fragile peace into peril again. Droves of criminals with lengthy rap sheets have been freed, and one has already murdered a pregnant 22-year-old woman.

How many more families will be torn apart in the opposition’s desperate bid for power? This question now haunts too many Nicaraguans.

You must be logged in to post a comment.