Editorial note: This piece is extremely pessimistic and lacks proposals but the writer touches several truths that gravitate in current Venezuela’s economy and society. Some of these truths are result of US Sanctions and the others are the result of bad economic policy.

By Carmelo Da Silva *

The brightest and most beautiful person I have had the privilege of meeting told me one afternoon, walking down a street in the center of Caracas, that it was transforming into San Juan de los Morros (a small city in Venezuela’s countryside). Although in reality those were not exactly his words, but rather: “this shit now looks like San Juan de los Morros.”

Like many things I heard before and like a good “Caraqueno”, what was said could be interpreted in multiple ways. Immediately it was a complaint, caused by being looking for meat at two in the afternoon and finding all the butchers closed.

But in a broad sense, he realized a more complex phenomenon: how a city like Caracas, known for its frenetic pace, cosmopolitan style and crowded streets at all hours of the day, almost without us noticing and nobody decreeing it, began to have a work schedule and commercial activity similar to that of the towns of the provinces, whose people rest at noon while the strongest sun passes and ditto the drowsiness associated with post lunch digestion.

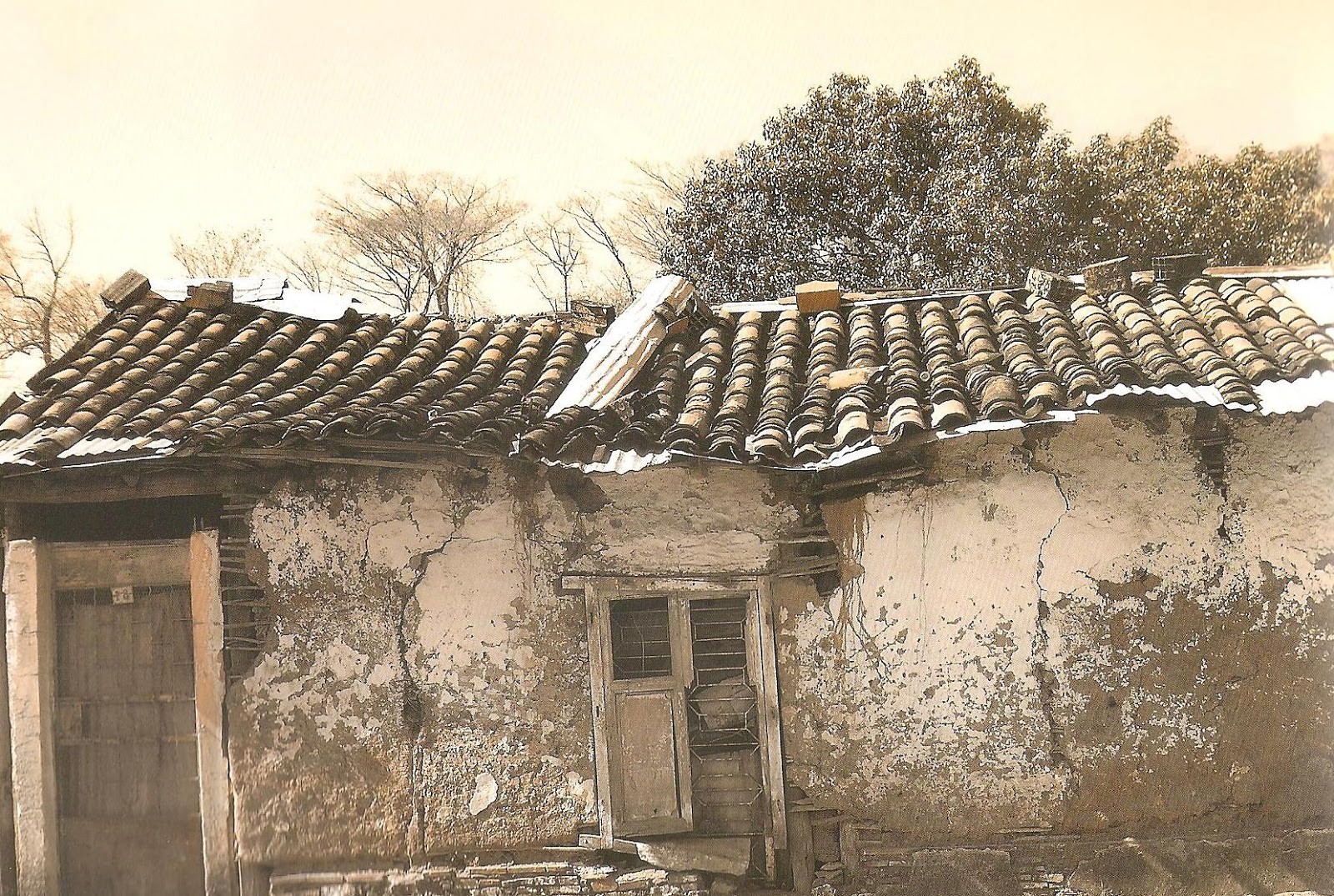

The fact is that since then that expression embodies for me the image, not only of Caracas, but that of all Venezuela when it comes time to understand the current situation: that of a country that was revolutionizing in the process of being a power, but suddenly, in the midst of the most complex and incredible conflict, it re-ruralizes in the bad sense of the term. In a few months Caracas becomes San Juan de los Morros and San Juan de los Morros and other similar towns are increasingly similar to Ortiz from Miguel Otero Silva’s novel (Casas Muertas).

Dead houses in the 21st century?

For those of us who live in Caracas, it is a little harder to measure what is happening, among other reasons because the government has managed the crisis so that the capital compared to the province is better armored. The electricity issue is the best example.

Since the March blackouts the SEN (electrical national network) has not recovered, the only thing that has happened is that the load is rationed in such a way that the entire province must sacrifice hours without electric service to give them to the capital. And the same happens with water, with gasoline, with food, with gas, etc.

It is not that in Caracas the light does not go out or the water is not troubled. This past weekend in several areas people were seen carrying water in makeshift outlets and tank trucks. But it is not an everyday thing, as it is in Maracaibo and in general everything that is beyond the “Puente de Coche”, the metropolitan distributor and the first viaduct to La Guaira, the three exits from Caracas to “Monte y Culebra” province.

Or it was not until now, because the truth is that at the same rate that people are moving to Caracas fleeing the provincial dead houses, in a few cases occupying spaces left by relatives who left the country, the precarious balance of the Caracan shield begins to falter.

The drop in figures

In a previous note we said that everything indicates by the end of this year the size of the Venezuelan economy will have been reduced by 70% compared to what it had at the end of 2013, that is, only six years ago. This is a contraction equivalent to that of countries that are experiencing war catastrophes, such as Libya, Syria or Yemen. And that far exceeds the Cuban special period, which is already saying a lot.

In any case, if the 70% forecast was confirmed by the end of this year, Venezuela would sneak into the top five of the ranking of the largest economic contractions in history, after Liberia (91% in 1980), Georgia (78% in the mid-80s ), Tajikistan (70% between 1989 and 1990) and Iraq (64% 1991).

The difference is that the political situation in Venezuela has not exploded, as was the case with the former each in its own way, from military invasions to popular rebellions. And perhaps the price to pay for it is that the economy and society in general are imploding by swallowing or expelling all the vital energy accumulated for years including its people.

And when we say imploding we must understand that we are no longer talking about a crisis in the conventional sense of the term. That is, we are not just saying that a country lost so much or how much of its production, that prices were raised at such or such amounts, unemployment rose or triggered the exchange rate, etc. All this is happening without a doubt, but beyond that we are talking about one where the vital sources of its reproduction as such – as a country – are collapsing, which carries with it the rest of things.

The main economic activity for decades of the Venezuelan economy – read oil – is in critical condition, producing 4 times below its level and everything indicates that it will continue to decline. This not only aggressively reduces national income, but also reproduces other internal problems such as the shortage of gasoline.

It is complicated to know the exact figures, but it is estimated that currently only 50 to 60 percent of the gasoline needed to supply the national market is produced, which explains why people spend long hours in the provinces in lines to stock up, an anomaly that implies an alteration of the already diminished economic activity beyond all the obvious discomforts.

It should be added that the virtual paralysis of the oil industry also means the depletion of other essential goods, such as fuels associated with the generation of energy for industrial use and fertilizers, the latter from petrochemicals.

As for the former, the complication of the electrical issue is largely explained by this reason, since if the current electricity generation is supported on the Guri hydroelectric power plant by more than 80%, it is largely due – although not exclusively – to that there is no fuel to activate regional thermoelectric plants. And the fact is that as long as this continues to be so, it will not only be impossible to reactivate the productive apparatus, but the trend will continue to be a decrease in the actual available supply of the SEN and its greater vulnerability.

In summary:

1) The country is running out of foreign exchange, paradoxically at a time when the dollarization of internal means of payment is being imposed, dollarization largely financed by the entry of remittances, something never seen before. In fact, until 2012 Venezuela was among the top 20 countries in the world exporting remittances: today the Central American countries dispute the first positions as recipients.

2) It is also running out of fuel both for vehicles to circulate and for industries to run. And neither are derivatives from industry (polymers for example) and agriculture, with all that this implies. In the same way, domestic and industrial gas is an increasingly scarce and precious asset. This problem is so serious that in rural areas of the country, people have already dispensed with its use for cooking, moving on to the old method of firewood, which causes problems of deforestation.

3) And we have less and less electricity, among other causes due to the lack of fuel for thermoelectric plants. In this sense, the issue of blackouts has no quick solution in sight. And if the SEN has not collapsed definitely, it is because the fall in demand caused by the same crisis compensates for the supply available.

4) It should be added that the main national productive factor, that is, labor, also is passing through a dramatic process of deterioration. To just refer to the most obvious issue, let’s talk about salary. Venezuela currently has the second lowest minimum wage in the world (1.9 US $ per month), only surpassed by Uganda (1.8).

This has resulted in this reference having disappeared, since even employers are forced to pay higher wages to retain their workers. Thus, in the private sector, salaries that are much higher than the official minimum can be observed.

A supermarket cashier can earn up to 800,000 sovereign bolivars and a specialized employee up to one million in some areas. This is 20 and 25 times the official minimum wage, but at the time we are talking about between 20 and 50 dollars a month, much less than the regional average and in the case of 50 dollars four times below the estimate of the basic family basket’s monthly estimated cost.

In the case of public administration the situation is even more dramatic: the average, including management and executive positions, is around 10 dollars a month.

5) The response of the workers to this reality is the labor exodus. In many cases this means also migrating, to the extent that a large contingent of all areas have emigrated. In others there is only internal displacement, with forced displacements from one side of the country to the other in search of better opportunities.

But in the vast majority of cases the exodus is occupational, to the extent that only very few are working on that for which they were formed or performed and today they swell the ranks of informality and widespread searching as a form of survival.

6) The great commitment of economic policy has been to create conditions for external and internal investment. However, at the same time it has applied a monetary tourniquet that is in fact asphyxiating the country, without necessarily translating into the promised exchange and price stability.

To size the issue, let’s look at three figures: in August, financial intermediation – the amount of deposits that are transformed into loans – fell to the historical minimum of 13%, which is undoubtedly a direct result of the bank reserve requirements applied by the BCV.

On the other hand, monetary liquidity – to which all conventional economists often blame inflation – until September increased 1,531.36%, not only a very marked slowdown compared to 8,537.68% in the same period last year but also quite late with respect to inflation, whose growth in the same period should be around 2,500%.

And with respect to this same indicator, it should be taken into account that all the liquidity circulating in the last week of September, amounted to 768 million US dollars, which accounts for the size of the monetary and financial contraction.

In the same vein, if all the national banks joined together to finance a loan, it could not exceed 50 million dollars: one eighth of the last investment made by the government in 2012 for the acquisition of Metro trains.

7) In conclusion: in the midst of the great contraction we are going through, there is less money circulating, with bolivars with less and less value and ridiculous levels of commercial productive credit.

RELATED CONTENT: Is the Economic War on Venezuela Over?

Caught with no way out?

It is really difficult to contemplate the Venezuelan situation without being filled with pessimism. Especially because the main forces responsible for what we have just described are very powerful and do not look encouraged to abandon their actions but rather the opposite.

On the one hand the US government and its policy of external asphyxiation through a blockade that began sanctioning officials and is already prohibiting the use of software by any citizen, not to mention the oil embargo operated around the dispossession of CITGO and the prohibition of commercialization of Venezuelan crude abroad.

And on the other, the Venezuelan government, with its “recovery” policy based on contracting the money supply, salaries and public spending to which an ultra-orthodox dose of zero deficit applies.

As paradoxical as it sounds in the case of struggling forces, the truth is that their efforts are complemented in the task of destroying the country, so they are an active part of the problem and are far from being part of the solution. And in this sense it is necessary to be very clear in the diagnosis: if with the gringo blockade it is really uphill to start some recovery process, with the economic policy of the Venezuelan government what was uphill becomes impossible.

But with the understanding that with the US government and its attitude – irresponsibly boosted by an important part of the Venezuelan opposition – there is not much to be done, the (few) hopes go through a change of correlation of forces within Chavismo that can take a turn to the current economic policy. That or the possibility of a broad agreement that is not only of the struggling elites or a relay to more progressive forces than the current ones. If nothing happens there is not much to expect that it is not sinking into national dead houses.

In this sense, assuming some of these changes work, the economic recovery plans have long been small. Venezuela needs a national reconstruction plan, which accounts for the main economic variables but which, in general, involves redoing the material basis of its own existence as a country that is dissolved or in the process of doing so.

And from this point of view, what we have to be aware of is that if the level of deterioration advanced to date is equivalent to that of countries at war or whose political-social orders crumbled – without either of them being exactly the same. case- then the exit from that state must be that of a post-war treatment.

When we say reconstruction we do not mean to go back to the past or to do what was done before. That is simply impossible, but what is possible is to do something better. In any case, by reconstructing, we basically understand what has been said in the previous paragraph: replenish the bases of material and social existence, which are a necessary condition for undertaking any recovery process.

To explain it with an example, let’s take into account the current government recovery plan. Assuming (which is not the case) that, as it is conceived, it can lead to a recovery process as long as investments arrive, consumption is reactivated, etc., it would be unfeasible as long as there is no material support. First of all there are no currencies to make the necessary imports.

But assuming there are, the immediate problem goes through the electrical issue, which would immediately collapse when industries, shops and home consumption are reactivated, as well as all other services such as electricity, water or gas. In the case of consumer goods the situation would not be different.

For the current case is not that there is a better supply than before in the sense that it has been produced or imported more, but that having less consumption there is greater availability on the shelves. And in that case, if the purchasing power was recovered, said availability would disappear immediately, giving rise to new hyperspeculative and hyperinflationary waves.

It is for this reason that isolated proposals such as raising wages to floating petro make no sense. Wages must be raised, but more than just that, it must be done in a context of generalized indexation of prices and wages and sustained improvement of supply. And for this, resources must be previously generated to finance it, while adapting the issue of electricity and services in general so that the picture does not worsen due to entropy.

By now, then, it should be clear that nothing you want to do will be possible by continuing to take the oil industry in the present direction. And the only activity with growth capacity and real multiplier effect that Venezuela has is that one. We can discuss whether this is desirable or undesirable. Of course, ideally, there would be others with the same potential and more diversified.

But it is not the case and in this historical moment to pretend otherwise is dilettante in the least bad of cases and criminal in the worst. There is simply no time or conditions for it, unless it is at the cost of great suffering of several generations on a bet more than uncertain.

The main teaching of the Venezuelan experience of the early twentieth century is that oil is not the excrement of the devil and is more like black gold. The deviations or excesses that have been derived from the Venezuelan model of accumulation based on oil income are not evils of oil itself, but the result of social, economic and political arrangements imposed by force through external interests. To pretend otherwise is not only puerile but to throw away the baby with the bath water.

In this sense, what is required is to rethink its use, but not to discard its usefulness. It is the only real possibility as we have said to avoid dead houses nationally, which in this case would not be that of some towns emptied after the oil boom but that of a country that emptied itself, diluted and exhausted, trapped among the worst interests it faced and a kind of post-rentist dystopia whose results we are suffering.

- Consultant of economic environment and political risk, collaborator of the Latin American Center for Strategic Analysis (CLAE)

Translated by JRE/EF

- orinocotribunehttps://orinocotribune.com/author/orinocotribune/

- orinocotribunehttps://orinocotribune.com/author/orinocotribune/

- orinocotribunehttps://orinocotribune.com/author/orinocotribune/

- orinocotribunehttps://orinocotribune.com/author/orinocotribune/

Tags: burocracy economic crisis Economy Electricity fuel shortages Migration production recovery US Sanctions Venezuela

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)