San Francisco Spends Hundreds of Thousands of Dollars for Covid-19 First-Responder Hotel Rooms Nobody Uses While Homeless Population Abandoned

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

By Joe Eskenazi | May 7, 2020

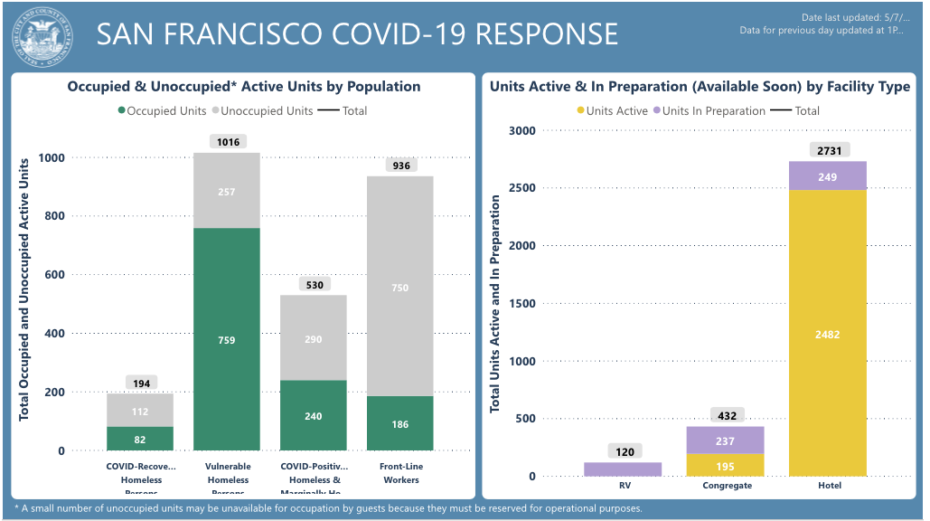

First, the good news: San Francisco has not devolved into a charnel house; we have not become New York City. Our first-responders have (ostensibly) not been exposed to COVID-19 at the levels city officials weeks ago feared would come to pass. They have not booked, en masse, into hotel rooms set aside for them: as of May 7, only 136 of the 936 hotel rooms set aside for first-responders are occupied. That means 750 are empty — an 80 percent vacancy rate.

And we’re paying for that.

On average, the per-room rate listed in the city documents we requested is $110. With food, security, and cleaning, that swells to $237 — but you don’t need those things for rooms nobody is staying in.

During hearings on April 29 and April 30, Supervisor Aaron Peskin posited that the city was spending $40,000 a day on unused first-responder hotel rooms — but he now says that figure is low. It might be quite low.

Rough, back-of-the-envelope math ($110 x 750) puts the city total paid for unoccupied rooms at perhaps $82,500 a day.

The contract for the 380-room Mark Hopkins hotel, designated for first-responders, lists room rates at between $130 and $150; city officials have said this hotel is sitting up to 90 percent vacant. Supervisor Matt Haney says the city may be spending $100,000 a day or even $140,000 a day on empty hotel rooms.

Our messages for Human Services Agency director Trent Rhorer, HSA finance and administration director Dan Kaplan, spokesman Joe Molica, and the general HSA press address have not yet been returned.

Regardless, this is a suboptimal situation. Front-line workers have complained to Mission Local that landing a room in a city-funded hotel is an onerous and opaque process, and others have bemoaned a less-than-robust information campaign among their colleagues.

Not even every qualifying first-responder who’d want a room appears able to get one — let alone the city’s homeless population.

RELATED CONTENT: Global Uproar Against the US for Changing World War II History

Bottom line: The city is paying for rooms it is not using, while thousands of homeless people, residential hotel-dwellers, and others are languishing outside or in unsafe conditions indoors. City officials have decried the ruinous costs of proactively placing the homeless in hotels — while, again, shelling out for 750 rooms that nobody is using.

That has to change, and city officials admit as much.

“We wanted to give first-responders the time to make use of these rooms. That hasn’t happened at the level we thought it would,” the HSA’s Dan Kaplan told the supes on April 30. “We acknowledge that at this point.”

Kaplan agreed that the Human Services Agency wanted to “get out of” its early deals for the InterContinental and Mark Hopkins hotels.

Mission Local has learned that, in the interregnum, the city has indeed made a shift. The 554-room InterContinental — which is owned by the same group as the Mark Hopkins — will be opened up for low-wage workers and their family members (we do not yet know how these people will go about getting rooms). This move was, in part, inspired by the results of UCSF’s four days of COVID-19 testing in the Mission — during which 95 percent of the people testing positive turned out to be Latinx.

In the meantime, rooms in this hotel, which had been largely empty, are being billed to the city at a minimum of $109 nightly. The city pays for 250 rooms, minimum, even if fewer rooms are occupied. Even, it seems, if far fewer rooms are occupied (In those recent Mission tests, 74 people came up positive — which wouldn’t figure to swamp the cavernous Intercontinental. UCSF’s Dr. Diane Havlir has stated that “three or four” of the test subjects are now utilizing the hotel program).

So, this is a positive development, especially for the Mission’s put-upon low-income workers.

But the city has still spent handily on rooms that went unused, while denying rooms to people who could use them. Whether to put San Francisco’s worst-off inside during a pandemic has been the subject of legislative warfare over the past month and change, with Mayor London Breed blowing off emergency legislation approved by all 11 supervisors.

Yet, aside from that ongoing debate over who should get a room, the city didn’t need to pay for hundreds and hundreds of rooms it wasn’t going to use.

During that April meeting, Peskin expressed dismay that the city out-and-out grabbed entire hotels for first providers instead of the model he, weeks ago, thought everyone had agreed upon — assuring hoteliers a guaranteed minimum payment for around 5 percent of the rooms and then agreeing rooms would be available to obtain in blocks of 100 as needed.

Kaplan acknowledged that the deal for the InterContinental was originally structured in this manner. But it appears the final deal was not, nor was the pact for the Mark Hopkins.

“I can’t believe we’re renting the entire hotel,” replied Peskin during the meeting. “My support for this was premised on maintaining a minimal guarantee and then scaling up. It’s not as if anybody else is renting hotel rooms. This seems to be an outrageous giveaway, frankly.”

But, here’s the thing — these may yet be the halcyon days of San Francisco’s COVID-19 era.

All of the work and spending and effort San Francisco has made thus far — which has, incidentally, highlighted the ludicrous nature of addressing serious, overarching national problems on a county-by-county basis — has been premised on the belief this would be a monthslong situation; we’d sit out the maelstrom and get back to business.

But what if we don’t?

City officials are, increasingly, taking on the mindset that this will be a far, far longer slog. And, when the fiscal year ends on June 30, we’ll be facing crushing deficits and a bleak new financial reality.

Bottom line: Our long-term problems may yet make these short-term problems seem trifling.

And the only way out is through.

Update: The Human Services Agency provided answers for some of Mission Local’s questions. but not all of them.

At the April 30 GAO committee meeting, you said there would be a meeting that day to determine what direction to take with regard to first-responder hotels, and what to do with some of our existing leases.

What was determined at that meeting?

We determined that we would attempt to repurpose the rooms at one of the two First Responder Hotels to make use of the rooms for vulnerable individuals in the community at high risk of exposure.

Today, the hotel ownership group agreed to our proposed use of the hotel rooms. The priority for this resource will be low wage workers and/or their family members, due to their increased risk of becoming infected. This is the population that the UCSF-Mission testing study revealed is at greater risk of exposure. There are 600 rooms at this hotel for this purpose. The transition to this population is in the early planning stages and will require the development of a site staffing plan and an outreach and referral process for eligible San Francisco residents.

Also, is there an accurate way to calculate the amount of money spent daily upon the unoccupied first-responder rooms?

We cannot share this information specific to the first responder rooms, as it would reveal the negotiated hotel room rates, which we are keeping confidential until the hotel procurement is completed so we don’t compromise future hotel negotiations. This is consistent with our response for this information from other media outlets and in consultation with the San Francisco City Attorney’s Office.

Finally, I would like access to the contracts for both first-responder hotels and vulnerable population hotels. I believe these to be public records. How do I go about getting that?

Our position on this to date is that we will not release contracts as we are involved in a rolling procurement/contract negotiation and that we do not want to release terms of existing deals because this may affect future negotiations. This is consistent with our response for this information from other media outlets and in consultation with the San Francisco City Attorney’s Office.

Featured image: Photo by Loi Almeron

You must be logged in to post a comment.