April Elections in Latin America: Background and Possibilities

Orinoco Tribune – News and opinion pieces about Venezuela and beyond

From Venezuela and made by Venezuelan Chavistas

By Saheli Chowdhury – Apr 8, 2021

For Latin America, the 2021 calendar is filled with elections of all kinds—presidential, parliamentary, gubernatorial, municipal, and even one for a constituent assembly. Two of these elections are to take place on the same day in April in two different countries—Ecuador and Peru. The election to select a Constituent Convention in Chile was originally scheduled for the same day, but has been postponed to May, citing the spread of COVID-19. These elections are taking place against a complex political background, with both countries suffering from devastation wrought by long-term neoliberal policies, foreign—especially US—intervention, right-wing media oligopolies engaging in smear campaigns against leftist candidates, and the ever-present threat of the Organization of American States branding any election with results not to the liking of the imperial power of the north, as “fraudulent.”

Second round in Ecuador—in the shadow of lawfare, fake news, and a state of emergency

In Ecuador, the second round of the presidential election, scheduled for April 11, is essentially a contest between the two dominant political currents in Latin America—neoliberalism characterized by privatization and servility to the United States, and 21st-century socialism promoting policies for socio-economic development. In the first round held on February 7, Andrés Arauz, an economist who held important positions during Rafael Correa’s administration, finished first with 32.7% of votes, a 12-point lead over conservative businessman and banker Guillermo Lasso, who finished second. These two candidates will contest in the second round.

RELATED CONTENT: What’s Happening in Ecuador?

However, the Arauz team’s journey has not been easy. Since the announcement of elections in June last year, there have been numerous attempts to prevent him from running by any means possible. Arauz was prohibited from registering his candidacy under the banner of the Movimiento Revolución Ciudadana (the Citizens’ Revolution Movement, CRM), and had to join forces with an existing political party in order to have his candidacy recognized, a process that set his campaign back by months. This should be viewed within the background of current president Lenín Moreno’s betrayal of the Citizens’ Revolution in particular and the people of Ecuador in general. Although Moreno was elected in 2017 on a promise of continuity with the CRM project pioneered by former president Rafael Correa, he betrayed the cause within months, and returned Ecuador to the neoliberal uncertainty and instability from which the Correa government had rescued it. Through an unconstitutional referendum in 2018, Moreno overhauled constitutionally appointed bodies including the judiciary to fill those positions with his loyalists. Using the private media conglomerates that Moreno immediately brought on side, he started demonizing the very administration which he had been part of for years, and under which he had served as vice president (2007-2013). At the same time, he unleashed an extensive judicial persecution against Correa and his allies, sending his own vice-president to prison; essentially disqualifying former president Correa from ever running for electoral office; and driving various leaders into exile. Meanwhile, as the economic situation worsened, the Moreno government signed a $4.2 billion loan deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and started implementing IMF-dictated austerity policies in early 2019. The country erupted in protests that reached a climax in October 2019, when thousands of Ecuadorians from indigenous groups, student and youth organizations, peasant movements, trade unions and other social platforms took the streets in a historic mobilization that lasted over 10 days. Although the protests were violently repressed by the police and the army, Ecuadorians have kept its legacy in mind as they are participating in the elections.

Throughout the electoral process, a multi-front dirty war has been carried out against Arauz, utilizing lawfare, fake news, and even uncertainties in ballot counting, in a manner increasingly common in elections across Latin America. For days after the actual voting on February 7, the National Electoral Council (CNE) of Ecuador neglected to declare official results, although Arauz led with an overwhelming advantage. This was in part due to Guillermo Lasso (CREO-PSC alliance) and indigenous leader Yaku Pérez (Pachakutik) being in a so-called “technical tie,” having both received almost the same percentage of votes. While counting proceeded, Pérez raised accusations of electoral fraud and demanded a recount, which was initially supported by Lasso, who later backtracked. When the request was turned down by Ecuadorian electoral authorities, the indigenous leader convened a national strike, called for a military takeover of electoral powers and nullification of the results. While all eyes were on the chaos over ballots and percentage points, the government of neighbor Colombia directly intervened in the electoral process, sending the Colombian chief prosecutor to meet his Ecuadorian counterpart in an attempt to get Arauz disqualified from the second round. Based on fake news published and amplified by right-wing Colombian outlets like Semana, it was alleged that Arauz had received financial support from Colombian armed insurgency group, the National Liberation Army (ELN). The unconvincing video circulated as “proof” of ELN endorsement for Arauz was soon debunked, not having been shot in Colombia as alleged, but in western Ecuador.

Since then, there have been further significant developments. Although the Pachakutik party had called on supporters to cast a blank ballot in the second round in rejection of “electoral fraud,” the president of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationals of Ecuador (CONAIE), Jaime Vargas, has recently endorsed Arauz. The National Confederation of Peasant, Indigenous and Black Organizations (FENOCIN), another key organization of the national indigenous movement, has also pledged support for the Arauz-Rabascall ticket. Another event was the revelation of Lasso’s multimillion dollar holdings in Florida, USA. Finally, what has generated concern in the electorate is Moreno’s declaration of a state of emergency in eight provinces of the country, apparently to contain the spread of COVID-19. However, many consider this to be a political tool being used to suppress voter turnout. “Moreno’s government has failed to control the pandemic, the healthcare system has collapsed,” said a voter from Guayaquil. “My city made headlines last year, with corpses rotting in the streets, but he has to declare an emergency now. This is to create fear among the people.” Candidate Arauz expressed similar concerns to Página12, saying that with the exceptional powers of the state of emergency, “the president of the republic could modify the electoral protocols… this makes us worry that the process and the result could be manipulated.”

For now, pollsters are giving Arauz a five to seven-point lead over rival Lasso. Joe Emersberger, who has reported extensively on Ecuador and is optimistic about Arauz’s chances, considers an Arauz victory important for Latin American regional integration. “He is very committed to regional unity, to working together with regional governments for the development of his own country and Latin America overall. He also wants to work with China… His victory will be huge for Latin American projects like UNASUR or CELAC,” Emersberger told Orinoco Tribune.

Peru—divided, uncertain, discouraged, seeking representation

It appears that the parliamentary and presidential elections in Peru, scheduled for April 11, are going to be the most unpredictable in recent memory. In the midst of the pandemic, with a political class discredited due to failed policies and corruption scandals, and a highly fractured electorate, the only certainty is that the presidential race will go to the second round. The fragmentation of the electorate is borne out by the latest polls, which forecast that six candidates out of 20 could pass to the run-off stage, five of them being in a “technical tie” for second place.

According to Ipsos Peru, Yohny Lescano of Popular Action is leading voting intentions with 12.1%, followed by neoliberal economist Hernando de Soto with 11.5%. Leftist Verónika Mendoza of Together for Peru is placed third with 10.2%, followed by ex-footballer George Forsyth (9.8%), and Keiko Fujimori (9.3%), daughter of jailed ex-president Alberto Fujimori and herself involved in a money-laundering case. Another pollster, IEP, put first place as a tie between Fujimori and de Soto, each with 9.8% of voter support, followed by the candidate of the extreme right, Rafael López Aliaga (8.4%), then Lescano (8.2%) and Mendoza (7.3%). Taking into account the margin of error, this represents a five-way tie. Other polls also gave similar results. But in all of them, 30-40% of the participants were undecided. The sample sizes were small, and participants were overwhelmingly from the cities, meaning voting intentions of the rural electorate remain untested, potentially skewing the polls.

RELATED CONTENT: Elections in Peru: Strength of the Left Not Reflected by Polls

“It is improbable that fujimorismo and neoliberalism have such acceptance among the population,” said political analyst Fernando Tuesta, “when these policies have harmed Peru so much. Rather, it is the ambiguity of the centrists that helps them win votes from both right and left… The problem for the leftist candidates is the division of votes among themselves. Support for Verónika Mendoza has grown over the last few weeks, but so has the base of Pedro Castillo [of Peru Libre] whose policies are more radical, and there is a radical sector that Verónika has failed to reach.” In Tuesta’s opinion, Mendoza’s campaign might suffer a repeat of 2016, when she narrowly failed to reach the second round because of fragmentation of the left base.

The left has been weak for decades in Peru, first broken by fujimorismo—a conjunction of neoliberalism and dictatorship, then decimated through years of repression and disinformation. In parallel, since the ushering in of neoliberalism in the early 1990s, Peru has seen neither peace or stability, nor had a corruption-free government. All presidents since Fujimori are under trial or arrest for charges of corruption or human rights violations, except Alan García, who only escaped justice by committing suicide. During the last five years, Peru has had four presidents. Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, elected in 2016, had to resign in 2018 amidst a corruption scandal. His Vice President Martín Vizcarra assumed charge, but was declared “morally incapable” by the parliament in October 2020, again over allegations of corruption. Interim president Manuel Merino’s mandate lasted five days, and since then another Congressman, Francisco Sagasti, has been in charge.

“The crisis in Peru is not simply political, but constitutional,” remarked Alex Main of Center for Economic and Policy Research. “The Fujimori Constitution is dictatorial, like the Pinochet Constitution, which Chileans discarded recently in a popular referendum. Peruvians want the same.” Indeed there were demands for a constituent assembly during nation-wide protests in late 2020. In their election manifestos, both Mendoza and Castillo have promised to hold a referendum for a new constitution.

Apart from rising poverty and inequality, lack of political representation is also a growing concern in the country. “Over 85% of us, Peruvians, are indigenous or mestizo, and belong to the popular class,” said José Carlos Llerena of the Peru chapter of ALBA Movements. “But a majority of the members of Congress are white, from upper or upper-middle class, who mostly live in Lima. They do not represent us; they represent multinational business interests.”

Gladis Vila Pihue of Together for Peru echoed similar sentiments. “Our constitution says that we are a multi-ethnic, multilingual country, but it is only on paper. We want a government—and a constitution—that will respect our rights. In Verónika Mendoza’s administration we will work for that,” she declared.

This aspiration for popular representation, which has led to constitutional reforms in multiple Latin American countries, originated in the Bolivarian Revolution pioneered by Hugo Chávez. Hence, using the “specter” of Chávez, Maduro and Venezuela, powerful media conglomerates are conducting a concerted assault against Mendoza. Possibly under this pressure, she called the government of Venezuela “a dictatorship” during the presidential debate on América TV, upsetting sections of the Peruvian left. “The demonization of Venezuela is so complete, that Verónika probably tried not to alienate parts of her support base,” said Peruvian journalist Juan José del Castillo in response to my question. “But why did she lie? The Venezuelan government is constitutional. She should have instead highlighted the devastation that country is suffering due to the criminal blockade by the US and its puppets. There are contradictions in her politics… It remains to be seen what her foreign policy would be if she gets elected.”

For that, we have to wait at least until this Sunday.

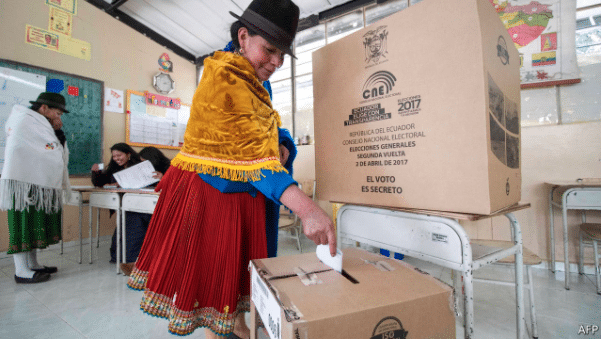

Featured image: Indigenous woman casting her vote in Ecuador. File photo courtesy of AFP.

Special for Orinoco Tribune by Saheli Chowdhury

SC/OT/OH

Saheli Chowdhury is from West Bengal, India, studying physics for a profession, but with a passion for writing. She is interested in history and popular movements around the world, especially in the Global South. She is a contributor and works for Orinoco Tribune.